Remembering Emanuel August Merck (1855 – 1923) on his 100th Death Anniversary

“His death was not only mourned by his family, but was also a painful loss for the company E. Merck, which he helped to bring to its present prosperity in his forty years as a partner, and for all of German pharmaceutical and chemical science and industry, which he promoted in an exemplary manner through his own collaboration, organizational activity and generous support.“ [1]

Many titles, a famous last name … but who was this man? No, he wasn’t the founder of the Darmstadt-based science and technology company Merck. That was Friedrich Jacob Merck (1621 – 1678), who received a license to operate the pharmacy that formed the historic core of the company. And no, he was not the “famous” Emanuel Merck (1794 – 1855), who in 1827 implemented the transition from a pharmacy as a craft to a science-based discipline and thus played a key role in deliberately advancing his field in Germany.

Emanuel August Merck, the grandson of the company’s founder, was selected to lead the pharmacy and play a crucial role in advancing the chemical-pharmaceutical factory “E. Merck” as one of its partners. His father, Georg Merck (1825 – 1873), shared similar scientific ambitions, sparking curiosity about the future of “E. A.”

Figure 1. Family tree beginning 1532 with Antonius Merck. © Merck Archive

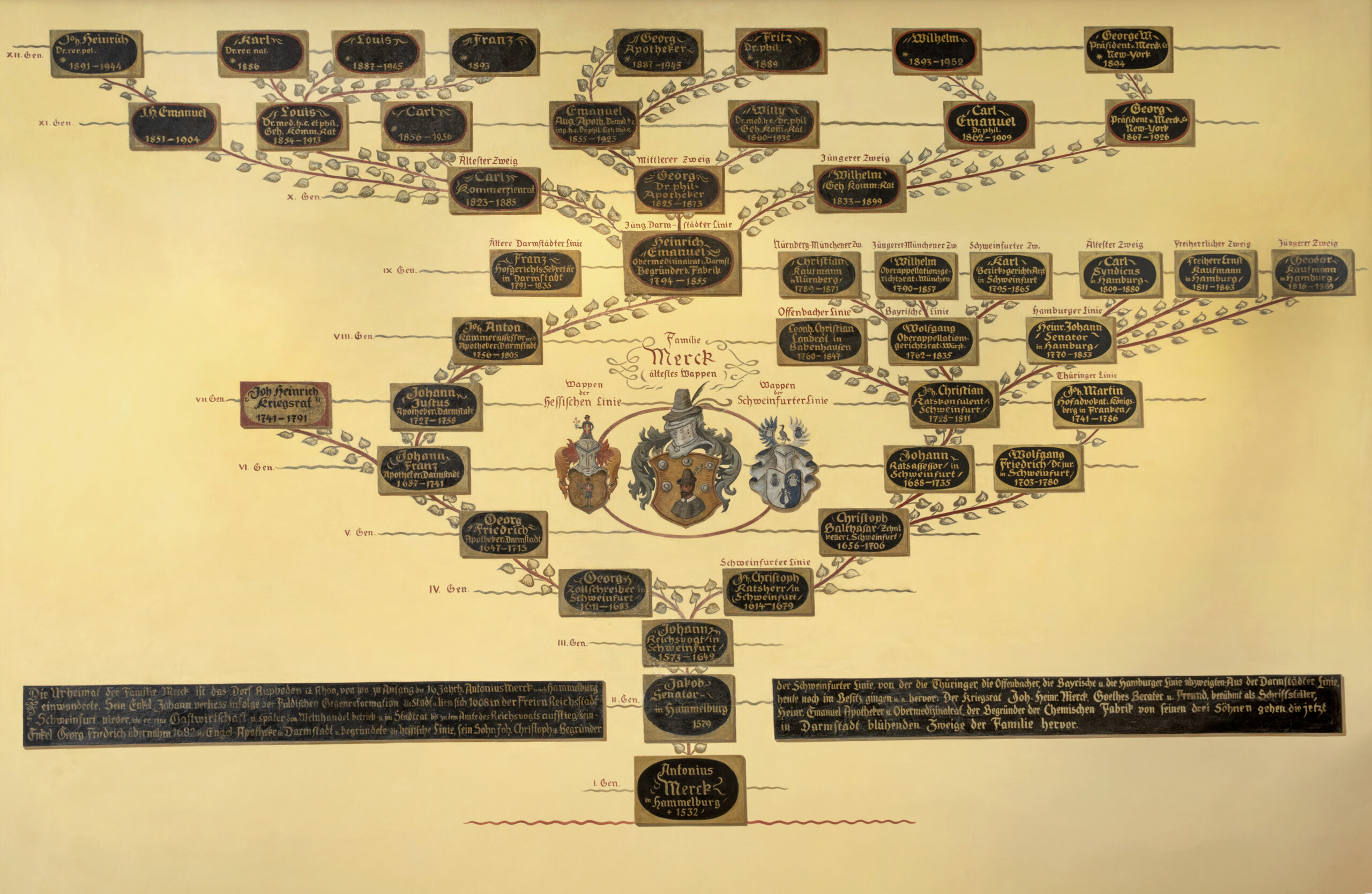

After finishing secondary school, he completed an extensive pharmaceutical apprenticeship in Bad Nauheim, Germany, and passed his first examination in 1875. To gain as much professional experience as possible, he traveled to various places, including Geneva, Switzerland. It was essential for him to have some international experience. After returning to Germany, he passed the pharmaceutical state examination in Würzburg in 1881 with “very good” marks. He completed his subsequent chemistry studies in Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, and obtained a doctorate with his thesis titled “Ueber die blausauren Salze organischer Basen” (On the blue-acid salts of organic bases) in 1883 [2].

Figure 2. Doctoral dissertation by E. A. Merck, 1883. © Merck Archive [MA Z01/QMerA]

Emanuel August Merck joined the company in the same year. Up to this point, his achievements had been quite nice, but not really spectacular … He did not have the ambition to make a name for himself through his own research; rather, he was more interested in the bigger picture.

Initially, he handled more down-to-earth work and was given responsibility for preparing and storing finished products for shipment. The organizational work to create the facilities for proper storage, filling, and packaging of many thousands of chemical and pharmaceutical products with various properties was tremendous [3]. In the decades that followed, E. A. commissioned the construction of extensive new buildings for the packaging facilities on the premises of the “new factory” [3,4].

Figure 3. In the old factory, 1886. © Merck Archive [MA Y01/af-18]

“However, in order to be able to make a decision that is as fair as possible to all interests regarding suitability for maritime transport and, in particular, with regard to stowage, it is not sufficient merely to know that the goods in question are flammable or corrosive or toxic; it is no less essential to know whether the goods in question can be packed in such a way as to exclude any danger. There is no doubt that the hazardous nature of a large number of chemical products can be rendered completely harmless by careful packaging adapted to the properties of the products.” [5]

In addition, as part of the Executive Board team, the young man oversaw the chemical quality control of the products manufactured at the factory, which helped establish the company’s reputation for producing high-quality products. By ensuring consistent quality control, he played a crucial role in maintaining the company’s success and future growth [6].

The Merck Control Laboratory – The “Conscience of the Factory”

High product quality, the greatest possible purity and reliability of substances are the clear goals. But are the testing methods also professional, independent, and scientifically sound? Since 1878, there has been the position of “control chemist” for “all analytical tests in the business, namely of finished chemical-pharmaceutical products, and then the presentation of some small products and individual experimental work.” In addition to the pharmacy laboratory, which had been responsible until then, a unit had to be set up to meet the high demands. E. A. Merck played a crucial role in these efforts [7].

Figure 4. The control laboratory, ca. 1900. © Merck Archive [MA Y01/ea-2122] and [MA Y01/ea-2123]

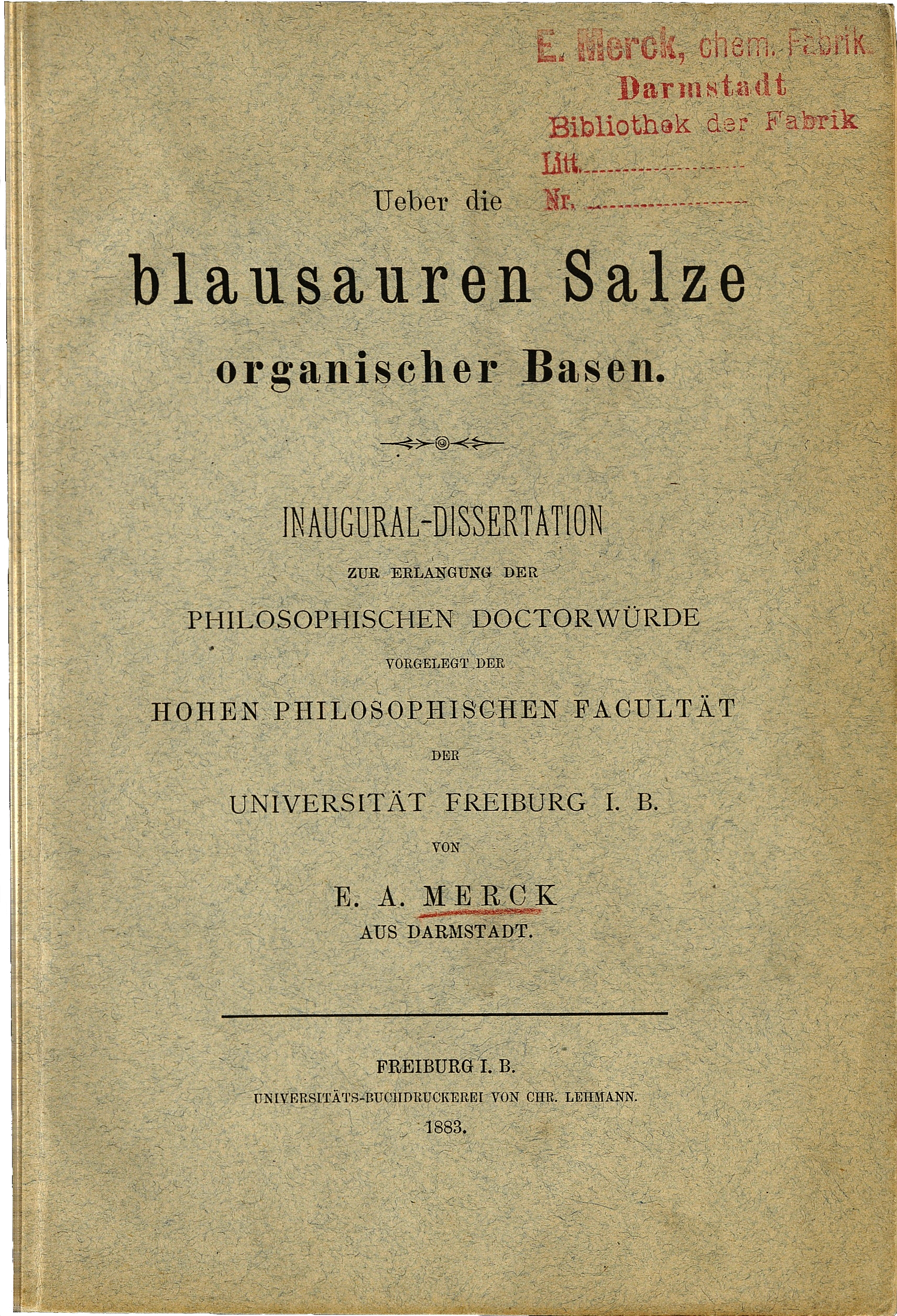

It was useful that since 1882, Carl Krauch (1853 – 1934) had been working as an analytical scientist for the company [8,9]. He contributed to the first work for standardized testing methods, which was published in 1888: “Die Prüfung der chemischen Reagentien auf Reinheit” (Testing chemical reagents for purity). In the preface to his book, factories were called upon to “introduce uniform designations and make a firm guarantee as to the extent of the purity [of their products]” [10]. The “guaranteed purity reagents” with the addition “pro analysi” appeared for the first time in the company price list in 1888 and became generally accepted purity standards among professional chemists – outside Germany as well [11].

Figure 5. left: Cover page of Krauch’s fundamental work on analytical chemistry; right: The first price list of Merck with “guaranteed pure reagents”. © Merck Archive [MA Y01/dok-12] and [MA Y01/dok-13-001]

Importantly, the autonomy of the control laboratory, which was independent of the production and sales departments, was ensured by its special status within the company. Just as it was directly subordinate to Emanuel August Merck at his time, its respective director in subsequent years was always directly subordinate to one of the company’s partners [7]. Of course, this also led to sometimes massive internal disputes with production and sales – but such things are usually beneficial to the cause!

Although the working conditions in the new factory, which relocated to Frankfurter Strasse in 1904, were “almost” optimal, analytical work, nevertheless, remained a complex field – and not everything always went according to plan. E. A. Merck said to Dr. Richter, Administrator of the City Hospital/Frankfurt-Sachsenhausen: “To my regret, I have gathered from your letter […] that you were not satisfied with some of my company’s deliveries. Although I make every effort, with the support of 5 chemists, to deliver everything impeccably, it is not absolutely impossible that inaccuracies of this kind may occur.” [12]

Figure 6. Control lab, 1920s. © Merck Archive [MA Y01/23541]

Patriarch and Supporter

According to the family magazine, “E. A. was uncomplicated and direct, a man of character, energetic and purposeful in his work, fair in his thinking and, like all temperamental personalities, not without rough edges.“ [13] Employees seemed to have agreed with that:

“In patriarchal fashion, he addressed the girls in the packaging department with ‘Du’, the German informal form of address. If he used the formal ‘Sie’, something had happened that should not have. […] The quality of Merck’s products was more important to him than anything else, and the yellow slip in his hand usually meant someone would be admonished; this slip meant that a customer had complained about the quality of the goods delivered to him.” [4]

Figure 7. Packaging department, 1920s. © Merck Archive [Y01/pro-714]

Emanuel August Merck was best suited for public service outside of the company due to his practicality and organizational talent. He was a strong advocate for the pharmaceutical-chemical sciences and industry and contributed to these fields through his participation in professional societies and associations, as well as through financial support.

Figure 8. Three of the partners in the eighth generation, from left: Willy Merck, Louis Merck, and Emanuel August Merck, 1910. © Merck Archive [MA Y01/01697]

He was appointed a member of the pharmaceutical examination board of the Technical University in Darmstadt early on in 1884 and remained so for the next 25 years. He also supported pharmacognostic and pharmaceutical-chemical work thereby purchasing material collections for academic study. For nearly a decade, he was a member of the Reich Health Council and made use of his extensive experience in the revision of the German Pharmacopoeia. The German Pharmacopoeia (Deutsches Arzneibuch, or DAB) is a legally binding reference work that contains quality standards and specifications for medicines and pharmaceutical substances used in Germany.

Verein Deutscher Chemiker (Association of German Chemists)

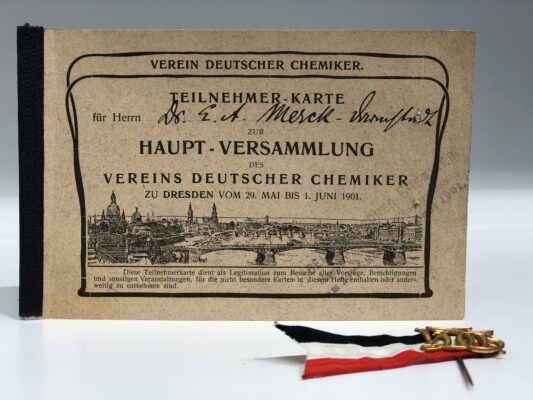

Emanuel August Merck was particularly closely associated with the tasks and interests of the Association of German Chemists (VDCh; Verein Deutscher Chemiker), a predecessor organization of today’s German Chemical Society (GDCh; Gesellschaft deutscher Chemiker). He served as Chairman from 1901 to 1906 [4]. As a student, his daughter Elisabeth became one of the few female members of the society in 1910 [14].

Figure 9. Participant card and pin of E. A. Merck for the general meeting of the Association of German Chemists in Dresden, Germany, 1901. © Merck Archive [MA X01-01906-01]

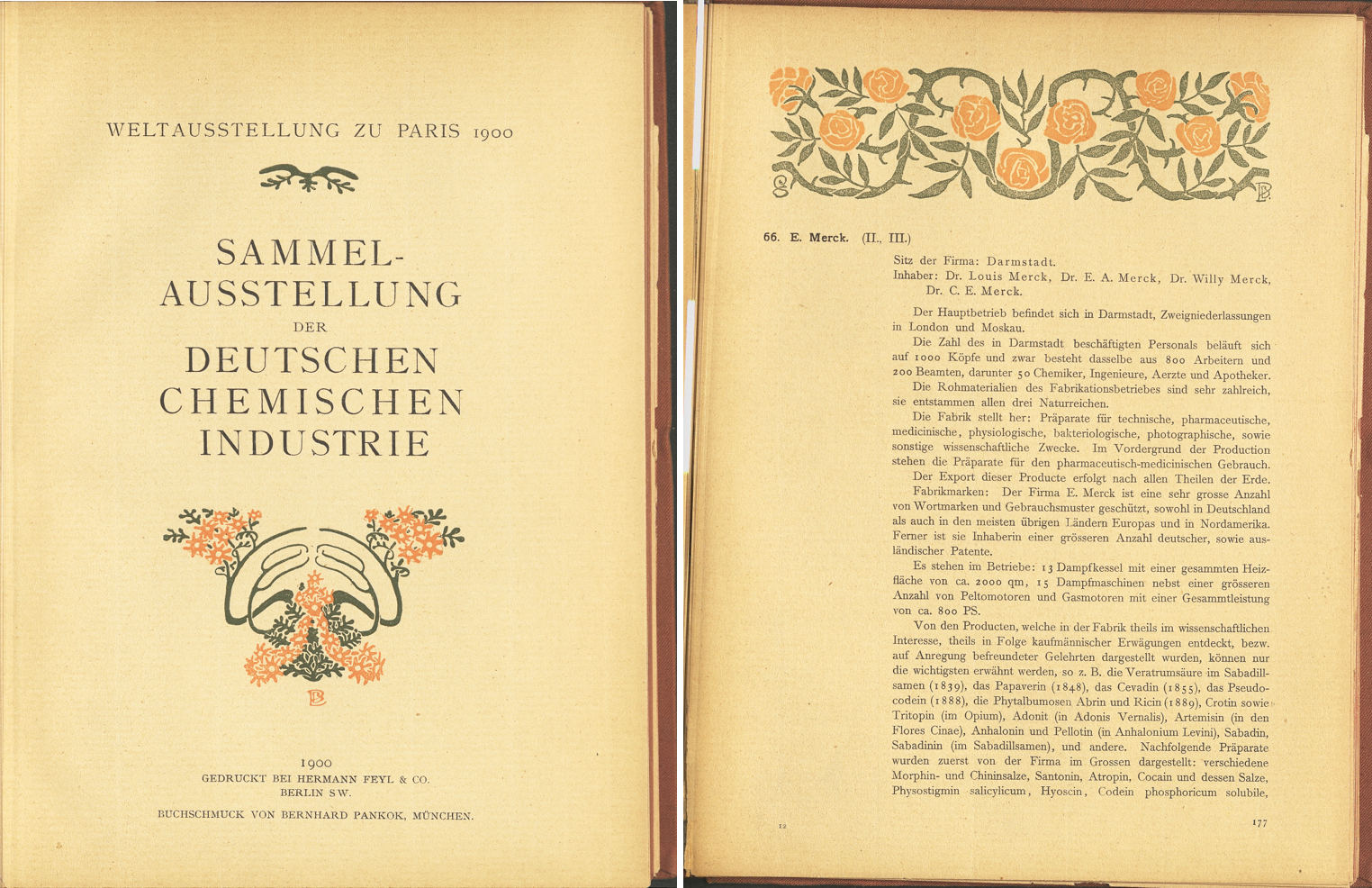

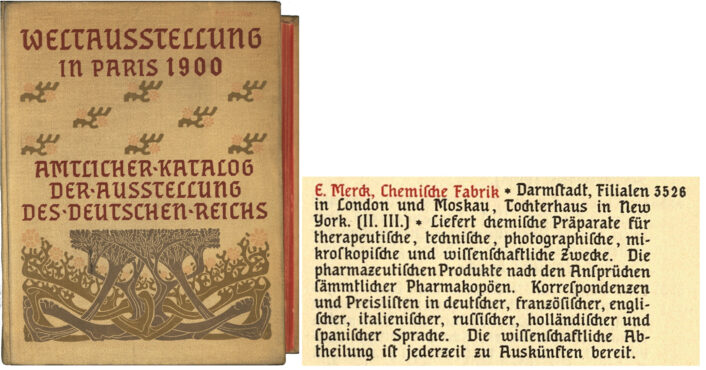

When the German chemical industry decided it would exhibit jointly at the Paris World’s Fair in 1900, it elected E. A. Merck to the board of the joint exhibition of the chemical industry [15]. In the same year, he was appointed “Medizinalrath”.”Medizinalrat” is a historical German title used to refer to a high-ranking government medical officer.

He was also a member of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science [4], a scientific research organization established in 1911 under the patronage of Kaiser Wilhelm II to promote scientific research in Germany, particularly in the natural sciences, mathematics, and medicine. It played a significant role in advancing German scientific research in the first half of the 20th century. In 1946, after the end of World War II, the society was disbanded and replaced by several individual scientific research institutions, including the Max Planck Society, which continues to be one of Germany’s leading research organizations.

Figure 10. Publication on the joint exhibition of the German chemical industry on the occasion of the World’s Fair in Paris, France, 1900.

Figure 11. Official catalog on the exhibition of the German Reich on the occasion of the World’s Fair in Paris, 1900.

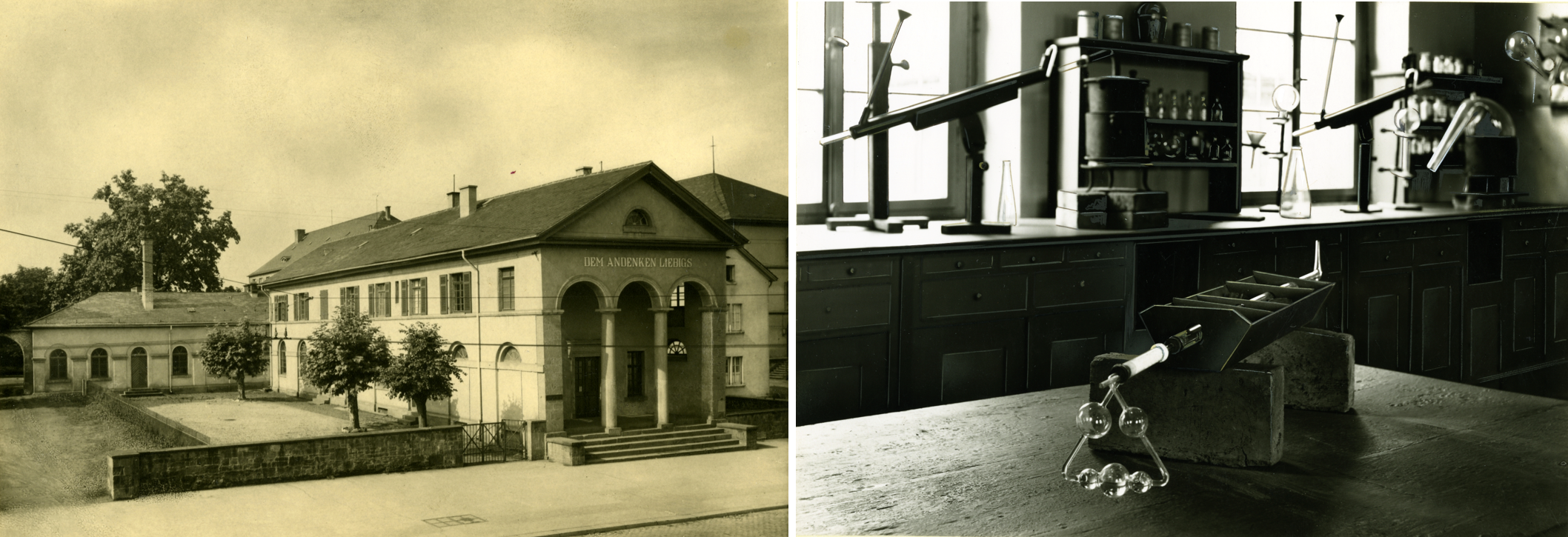

Liebig Museum, Giessen, Germany

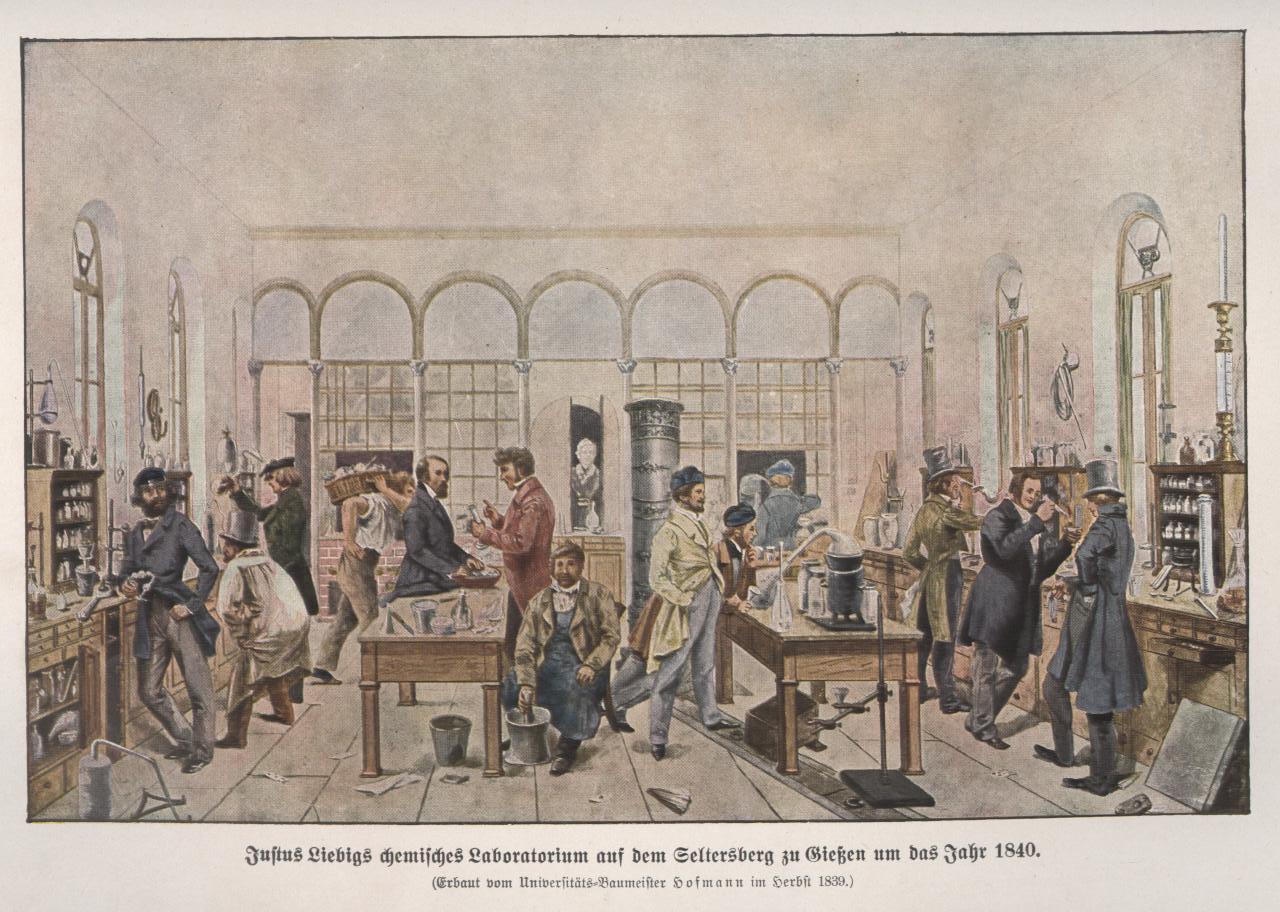

Emanuel Merck was passionately committed to preserving the laboratory of Justus von Liebig (1803 – 1873), a friend of his grandfather and under whom his father Georg had studied.

Figure 12. Justus Liebig’s Analytical Laboratory in Giessen, around 1840, painted by Wilhelm Trautschold (1815 – 1877). Illustration in: Library of general and practical knowledge, Volume 3, Deutsches Verlagshaus Bong u. Co., Berlin, 1912 [https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/19/Justus_von_Liebigs_Labor%2C_1840.jpg?uselang=de]

At the beginning of the 20th century, this important site in the history of the chemical industry was in a very poor state. Dr. Max Buchner, Executive Board member of the electrochemical department of C. F. Boehringer & Söhne Waldhof-Mannheim, Germany, a pharmaceutical company founded in 1885 by Christoph Heinrich Boehringer in Mannheim, and is today, known as Boehringer Ingelheim, wrote the following to “Medizinalrat Dr. E. Merk” about a visit to Giessen in 1903:

“The work premises of the famous chemist now no longer give an indication that here he and his disciples once inaugurated a new era of scientific chemical education and experimental research, to which we Germans owe not only our present dominance in scientific and technical chemistry, but also a large part of our present national wealth. … We German chemists would have the sacred duty to reconstruct this former model site … again. … I imagine the realization of the idea in such a way that the laboratory is restored to the condition in which it was under Liebig …, that furthermore, as far as attainable, all apparatus, instruments, manuscripts, works of Liebig, and whatever else relates to him, are collected there. … In view of the forthcoming celebration of the 100th anniversary of Liebig’s birth, I should immediately make a suggestion to this effect in the “Zeitschrift für angewandte Chemie”, so that the Verein Deutscher Chemiker (Association of German Chemists), which has created a Liebig Medal, will take the matter in hand. I submit it to you, esteemed Medical Councillor …, since you as chairman of the Association of German Chemists and outstanding citizen of Hesse, who also has the full confidence of the Hessian state government to a high degree, fulfilled all the prerequisites which would be necessary for the realization of the idea.“ [16]

In 1903, Merck submitted a request to the Grand Ducal Ministry of the Interior for the “transfer of the former Liebig Laboratory in Giessen by donation for the purpose of transforming it into a historical museum of chemistry.“ [17] Yet the authorities attempted to block the matter. Significantly, Merck wrote in February 1905 to the chemist Jacob Volhard (1834 – 1910; Volhard–Erdmann cyclization reaction, Hell–Volhard–Zelinsky halogenation), a former student and assistant of Liebig:

“The matter with the Liebig Laboratory in Giessen is not moving forward at all. Our ministers are terribly petty gentlemen […] I therefore consider it urgently necessary that we go public with the matter and publish an article in the feared Frankfurter Zeitung. [I] would be […] grateful to you, if you would pen this article for me as you are such a good writer. I fear that if I wrote it, I would be a bit too sharp, which would not be good either.” [18]

It took a further seven years of tough negotiations until E. A. Merck could report to his friend Carl Duisberg (1861 – 1935), General Director of Bayer in Leverkusen, Germany, the following:

“Dear Duisberg! Today I can inform you that at the beginning of the week, I acquired the old Liebig laboratory from the city of Giessen for myself.” [19]

In 1918, it was finally possible to transfer the Liebig laboratory to the Liebig Museum Society in Giessen [20]. Merck was a member of the Board and later became Honorary Chairman of the Liebig Museum Society. [4]

Figure 13. Liebig Museum in Giessen, Germany: Exterior view, undated [MA Y01/13700-009] and five-ball apparatus (Liebig’s apparatus for organic elemental analysis). © Merck Archive undated [MA Y01/13700-002].

Deutsches Museum München

E. A. Merck had been a member of the Deutsches Museum in Munich since 1906 and supported the establishment of the “Chemistry” section. The Deutsches Museum München, founded in 1903, is today one of the world’s largest science and technology museums with a long tradition. In its early years, E. A. Merck also wanted to help to make it an outstanding place for imparting science and technology and for promoting a constructive dialogue between science and society.

Among other things, he donated the “panel with the listed alkaloid preparations under glass“ shown in Figure 14 [21].

Figure 14. Panel with listed alkaloid preparations, Deutsches Museum München, Germany. © Inv. No. 28444-28543

His commitment to the historical pharmacy exhibited at the Deutsches Museum was also important. In 1914, Emanuel August Merck sent out a circular to German pharmacists to solicit objects as donations. By the end of July, a small but beautiful collection of historical objects from a wide variety of pharmacies in what was then the German Empire had been collected. Everything was collected in Darmstadt and then sent to Munich in mid-October 1914. However, the outbreak of World War I brought this collection campaign to an abrupt end.

In recognition of his achievements, Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig bestowed the title of “Geheimen Medizinalrath” on E. A. Merck in 1915. “Geheimer Medizinalrat” is a historical German title used to refer to a high-ranking government medical officer. In 1918, on the occasion of the company’s 250th anniversary, the University of Giessen awarded him the honorary degree Dr. med. h. c. in recognition of his services to science and the preservation of the Liebig Museum [22]. The Technical University of Darmstadt conferred the distinction of Dr. Ing. h. c. to E. A. Merck as a supporter of pharmacy and leader of the industrial company of world renown [3,11,22].

Many titles and a highly dedicated man – that was Emanuel August Merck!

Figure 15. Visit of the Grand Duke and Duchess of Hesse-Darmstadt on the occasion of the 250th anniversary of Merck in 1918. © Merck Archive [MA Y01/00312]

Note

The Merck Archive is protected as ‘nationally valuable cultural property.’ It includes the international corporate archive with handwritten and printed documents (correspondence, contracts, patents, laboratory journals, manufacturing instructions, plans, or advertisements), photos and films, books and magazines, sound recordings and digital storage media, as well as a family archive (estates, correspondences, and autographs). The oldest documents date back to the 16th century.

A public exhibition with a variety of objects and an art collection complement the holdings.

References

[1] Obituary in: Mercksche Familien-Zeitschrift 1923, volume IX, p. 1.

[2] E. A. Merck, Dissertation 1883. Merck archive: MA Z01/QMerA.

[3] Obituary for Councillor Dr. Emanuel Merck, Die Chemische Industrie 1923, 46(11), 161.

[4] Commemoration of E. A. Merck, Das Merck-Blatt 1955, 3, 3.

[5] Letter from E. A. Merck regarding the book by Dr. J Aeby entitled ”Dangerous Goods“, March 2, 1911. Merck archive MA B/24b.

[6] Commemorative speech for E. A. Merck. Merck archive: MA B/24a.

[7] Ingunn Possehl, Die Entwicklung der Analytik in der pharmazeutischen Chemie, Mitteilungen, Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker/Fachgruppe Geschichte der Chemie, Frankfurt/Main, Germany, Bd 9, 1993.

[8] Armin Wankmüller, Carl Krauch, Neue Deutsche Biographie 1979, 12, 679.

[9] MA F6/12: activity report of Albert Schumacher, 1928, p. 6, p. 48.

[10] Carl Krauch, Die Prüfung der chemischen Reagentien auf Reinheit, Darmstadt 1888. Preface.

[11] MA B/24a: Commemorative speech E. A. Merck.

[12] MA B/24a: E. A. Merck to Dr. Richter, administrator of the City Hospital/Frankfurt-Sachsenhausen, Nov. 23, 1908.

[13] Mercksche Familien-Zeitschrift 1923, volume IX, p. 2.

[14] MA F10/3a.

[15] World’s Fair in Paris: Joint exhibition of the German chemical industry, 1900, p. VIII.

[16] MA F3/21: Max Buchner, C. F. Boehringer & Söhne Waldhof-Mannheim an E. A. Merck, March 29, 1903.

[17] MA F3/21: Request by E. A. Merck to the Hessian Ministry of the Interior regarding the gift of the Liebig laboratory to the Association of German chemists, June 17, 1903.

[18] MA F10/21: E. A. Merck an Volhard (Halle), Feb. 18, 1905.

[19] MA F10/21: E. A. Merck to Carl Duisberg, Sept. 2, 1910.

[20] MA F10/22: E. A. Merck to the mayor of Giessen regarding the return of tax slips, Aug. 1, 1918. It is not indicated when the transfer took place.

[21] MA V15/550: Correspondence.

[22] MA A/1064.

Authors

Dr. Sabine Bernschneider-Reif, Head of Corporate History Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany

with the collaboration of Katja Glock and Peter Conradi

Also of Interest

The place of Liebig’s first experimental lectures and part of the Liebig Museum caught fire

Including the Liebig Museum and the Deutsches Museum