Our bodies are a vast ecosystem of microbes, many of which seem to be essential to good health and others that can cause harm, include those that live in our mouths. The precise range of such commensal microbes changes with changes in our diet.

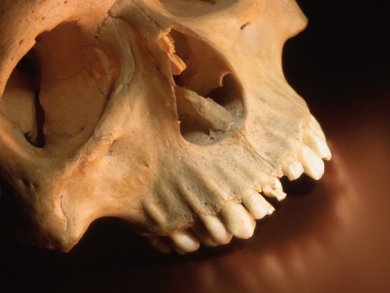

Researchers at the University of Adelaide, Australia, and their colleagues have used calcified dental plaque (dental calculus) residues from the teeth of 34 human skeletons dating to 10,000 years ago to investigate the transition from our hunter-gatherer ancestors to agricultural societies dependent on carbohydrate-rich crops, such as wheat and barley. The findings based on their principal-components analysis (PCA) of the analytical data suggest that the oral microbes present on teeth 10,000 years ago were not dissimilar to those of the medieval period. However, there was a shift to tooth-rotting cariogenic bacteria some time during the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century due to the advent of industrially processed flour and sugar.

- Sequencing ancient calcified dental plaque shows changes in oral microbiota with dietary shifts of the Neolithic and Industrial revolutions,

Christina J. Adler, Keith Dobney, Laura S. Weyrich, John Kaidonis, Alan W. Walker, Wolfgang Haak, Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Grant Townsend, Arkadiusz So, Kurt W. Alt, Julian Parkhill, Alan Cooper,

Nat. Genet. 2013.

DOI: 10.1038/ng.2536