Neutrophil granulocytes, a group of specialized white blood cells, react to bacteria by releasing serine proteases. These are enzymes that cut up other proteins to activate signal molecules. These are for example chemokines. The active signal molecules then guide other immune cells to the focus of inflammation in order to destroy the pathogens.

A research team led by Dieter Jenne, Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology, Martinsried, Germany, has discovered a previously unknown protease in humans: neutrophil serine protease 4, or NSP4. NSP4 differs from the other three known neutrophil serine proteases, as it cuts proteins that have the amino acid arginine at a particular point. All NSPs are similar in molecular structure, but have a different recognition motif. It may be possible to harness this difference to develop an active substance that specifically inhibits NSP4, thereby reducing the immune reaction.

In terms of evolutionary history, NSP4 is the oldest of the four known neutrophil serine proteases. Using gene sequences, scientists have shown that the enzyme has hardly changed through hundreds of millions of years of evolution from bony fish to humans. That would indicate that NSP4 regulates a fundamental process.

The fact that the enzyme remained undiscovered until now is because it occurs at a much lower concentration than the other three proteases.

NSP4 could provide a new target for the treatment of diseases that involve an overactive immune system, such as rheumatoid arthritis.

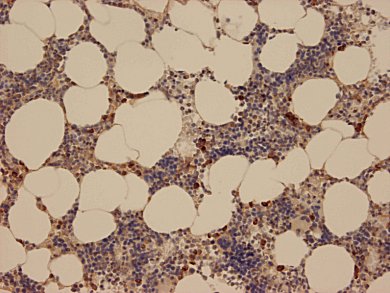

Image: Microscope image of normal human bone marrow tissue with stained NSP4 in myeloblasts and myelocytes. © MPI of Neurobiology

- Max Planck Society, Munich, Germany