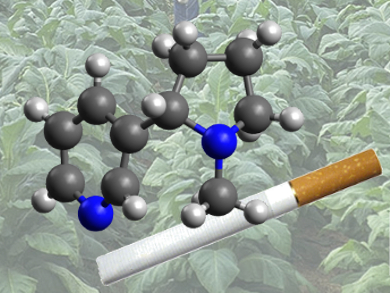

Mankind consumes a great deal of tobacco, most commonly in the form of cigarettes. Worldwide, roughly 15,000 kg of nicotine from tobacco makes its way daily into smokers’ lungs. That alone is sufficient reason for us to consider this particular natural product more closely.

How and why does the tobacco plant actually make nicotine, and what happens with it and with the smoker after consumption? Above all we want to look at why what at first glance appears to be a completely nonsensical practice – inhaling the combustion gases of fermented tobacco leaves – has for centuries been a celebrated pleasure, and why it can prove so difficult to resist.

Despite the high cost, despite all the statistically documented health risks, and despite even the clear warnings printed on cigarette packages in some countries – smokers continue to smoke almost unaffected. This in itself offers sufficient grounds to look more closely at routes that tobacco follows, the chemical changes it undergoes, and how it is that nicotine manages to prevent so many of us from wanting to (or being able to) set it aside.

1. Tobacco as a Medicinal Herb

When the tobacco plant first reached European shores in the 16th century, it was cultivated as a decorative plant. Jean Nicot (1530–1604), envoy from the French court, became acquainted with the new plant in the Royal Gardens in Lisbon, Portugal, heard about its wondrous curative powers, and popularized it in Europe. Tobacco soon acquired a positive reputation – which it retained for centuries – for uses as diverse as mitigating obesity, corns, chilblains, worms, warts, plague, toothaches, migraines, and numerous other afflictions [1].

It was remarkable not only for its breadth of application, but also for the many forms of its administration: as tinctures, infusions, and salves for external use, powders for the nose, leaves for chewing, tea to drink or smoke to inhale, and finally, there were even tobacco enemas reputed to bring the dead back to life [2]. The latter may cause one to cringe, but many odd ways of ingesting tobacco remain widely popular today.

2. Forms of Tobacco Consumption

2.1 Chewing

In Europe, the chewing of tobacco represents one of the oldest ways of enjoying it. This tradition, just like smoking, was learned from watching the indigenous peoples of America, who during the day often kept tobacco leaves in their cheeks which they had previously treated with limestone. This practice made it easier for them to tolerate both thirst and hunger. The term “chewing tobacco” is therefore misleading, since such tobacco (e.g., a “quid”) is never actually “chewed”. In the Thirty Years’ War, Swedish soldiers were especially known for their heavy use of this form of tobacco, and until today it remains very popular in Scandinavia.

2.2 Snuffing

The consumption of snuff developed somewhat differently. This application actually dominated tobacco consumption for almost the first two centuries after the introduction of the substance in Europe. Both men and women – from every societal class – once made frequent use of snuff, always with the goal of introducing the powder into the nose as gracefully as possible. Snuff, more crumbly than chewing tobacco, was kept in little tins. Ornately designed and elaborately decorated or painted, snuffboxes became very fashionable, also serving as status symbols. For a time, as much as 90 % of the tobacco consumed was stuffed into the nose [2].

2.3 Smoking

The smoking of tobacco gradually established itself in Central Europe around the middle of the 17th century. This meant one reached frequently for a pipe, in those days made out of clay. Clay pipes of course did not last forever. Hence, the manufacture of clay pipes in so-called “pipe bakeries” became a lucrative enterprise, helping the small Dutch city of Gouda to develop an international reputation. Pipes made of wood became popular at a later date, thanks to their being less fragile, but like the tobacco they contained, they often soon went up in smoke.

In the Biedermeier period (ca. 1815–1848), pipes made of porcelain became fashionable, despite many smokers experiencing burnt fingers. Starting in 1723, pipes made of meerschaum appeared, a mineral (also called sepiolite) traditionally acquired in Turkey. Connoiseurs swear by meerschaum pipes (preferably carved, as opposed to pressed from powder), and also by wooden ones made from briar root (french “bruyère”), i.e. wood from the species arborea erica, which is highly resistant to burning. Pipe manufacture became a remarkably important commercial activity, and just like the snuffbox, one’s pipe became a symbol of profession and status.

The smoking of tobacco in the absence of other paraphernalia, but instead “wrapped in itself” (i.e., as a cigar), became first known in Spain and Portugal. This, too, soon developed into a status symbol, reserved at first for the aristocracy. After the conquest of Spain, Napoleon’s soldiers brought cigars to France, and they quickly spread throughout a snuffing and pipe-puffing Europe.

3. The Triumph of the Cigarette

3.1 From 16th to 19th Century

|

As early as the 16th century, Spanish colonialists were smoking “papelitos” – small amounts of shredded tobacco wrapped in cornhusks or paper; but the real march of the cigarette towards predominance did not get underway until the late 18th century. That was when soldiers, especially from the Turkish and Russian armies, began wrapping tobacco in paper for smoking. Soon these “papirossa” were considered presentable even in polite society: in St. Petersburg and Constantinople, little tobacco rolls – enclosed in tissue paper – could be obtained in the form of hand-rolled finished products, and these became very popular. The Crimean War (1853–1856), and also the Russian nobility, saw to it that the “cigarette” gradually became common throughout Europe [3].

Soon, cigarettes became an object of mass production: as early as 1785 the Royal Tobacco Factory in Seville, Spain, made cigarettes, and until the middle of the 19th century this plant remained Europe’s largest commercial producer. Most of its workers were women, by the way, one of whom in fact became world famous – Carmen, of the opera by French composer Georges Bizet (1838–1875). In the first act, along with the other women working with her in the cigarette factory, she sings about the seductive nature of the rising smoke.

The first cigarette factory in Germany was established in 1862 in Dresden, and Dresden remained an important site for the tobacco industry. Certainly the most unusual cigarette factory from an architectural standpoint was erected there in 1909. The Yenidze Cigarette Factory was built to resemble a mosque, based on plans by the architect Martin Hammitzsch. Today, the so-called “Tobacco Mosque” serves as an office building and restaurant.

In Germany, tobacco varieties for cigarettes were imported mostly from the Ottoman Empire. These embodied a whiff of the Orient and the exotic, which the cigarette manufacturers effectively invoked in their advertising campaigns. Brand names and packaging with imaginative design were reminiscent of the tales from Arabian Nights: Salem (Yenidze), Genuine Orient No. 5 (Waldorf Astoria Hamburg), Saba (Garbaty), or Nil (i.e., “Nile”; Regie). Until 1920, the latter was actually a mixture containing 8 % cannabis!

3.2 The 20th Century

The First World War saw an incredible increase in cigarette consumption. Soldiers tended to smoke a great deal in any case, but cigarettes were also included in the daily rations for several armies. Upon their return home, the troops did not show much desire to quit the habit.

Until the 20th century, pipe and cigar smoking were strictly reserved for men [3]. Indeed, smoking in general was regarded as unseemly for women. Men were even expected to avoid smoking in the presence of women; in a proper household, in order to smoke, the men would leave the room, taking their cigar and pipe utensils with them, and adjourn to the study. To keep the delicate senses of the ladies from being annoyed by the slightest whiff of tobacco smoke, gentlemen often changed into special garb for this purpose: a “smoking jacket”.

It was not until the Roaring Twenties that cigarettes became socially acceptable for women – a cigarette could be smoked rapidly, and it was thin, elegant, and innocently white. Above all, in the hand of a woman, a cigarette with a genteel cigarette holder became a stylish accessory, one that radiated a certain air of exclusivity. With the introduction of filter cigarettes, however, this elegant fashion began to disappear more and more. Until the middle of the 20th century, public smoking by women remained somewhat frowned upon.

3.3 The American Blend

As early as 1881, the American James B. Duke (1856–1925) began to cultivate the milder American varieties of tobacco on a large scale in Virginia, applying new procedures for drying and fermentation. Thanks to modern production methods, cigarettes became inexpensive, machine-made, mass-produced articles of consistent quality. Cigarette consumption in the United States, and all over the world, increased massively toward the end of the 19th century. From the start of the 20th century, the “American blend” dominated the market, and revolutionized smoking: smoke from the new formulations was easier to inhale into the lungs, and thus provided a faster “kick”. Fussing around with awkward accessories, or acquiring the special dexterity demanded for “rolling your own” – all that became a thing of the past.

The development of marketing strategies entailing massive amounts of advertisement helped provide new impetus to cigarette consumption. The “Camel” brand attached its image to exotic Africa with dromedaries and pyramids, “Lucky Strike” presented themselves as alternatives to fattening chocolate, and the “Marlboro” brand was launched in 1927 specifically as a cigarette for women [3].

3.4 The Cigarette as a Currency – and a Symbol for the American Way of Life

It was not until after the Second World War that American cigarette brands captured the German market. A destroyed Europe tried to get by at first with leaves from tobacco plants grown on the balcony, or in an emergency by stuffing oak leaves into one’s pipe. Tobacco was strictly rationed, and could only be obtained with an official “smoker’s card”. But for both civilians and soldiers, tobacco had become an indispensible sedative. The “American Blend” or simply “Ami” was so coveted that in Germany it became a universal currency on the flourishing postwar black market [4]. The direct exchange of goods (“bartering”) became ever more popular, and “cigarette currency” came to be regarded as a new, more stable measure of value.

After the establishment of the Federal Republic of Germany, American cigarettes became a symbol of the new, modern, and cosmopolitan Germany. The “American Way of Life” ran directly through the worlds of fashion, music, movies – but also through the lungs. But what does tobacco actually contain?

Find out in the second part of this series.

References

[1] B. Schäfer, Chem. Unserer Zeit, 2008, 42, 330 (in German). DOI: 10.1002/ciuz.200800464

[2] Über den Tabak, C. Maronde, 1976, Fischer Taschenbuchverlag, Frankfurt a.M. (in German). ISBN: 3-596-21817-9

[3] H. Spode, Kulturgeschichte des Tabaks in Alkohol und Tabak, (Eds.: M. Singer, A. Batra, K. Mann), 2011, 13, Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart (in German). ISBN: 978-3-13-146671-6

[4] Deutsche Geschichten – Schwarzmarkt (in German).

The article has been published in German as:

- Starker Tobak – Unsere Lust und Last mit der Zigarette,

Sabine Streller, Klaus Roth,

Chem. Unserer Zeit 2013, 47, 248–268.

DOI: 10.1002/ciuz.201300636

and was translated by W. E. Russey.

The Chemistry of Tobacco – Part 1

Looking at the history of tobacco consumption – from chewing and snuffing to smoking

The Chemistry of Tobacco – Part 2

What does tobacco contain and which chemical changes happen between the harvest and a finished cigarette?

The Chemistry of Tobacco – Part 3

How does a tobacco plant synthesize nicotine?

The Chemistry of Tobacco – Part 4

What does cigarette smoke contain and what does nicotine do to the smoker?

The Chemistry of Tobacco – Part 5

What happens when a smoker tries to quit?

See all articles by Klaus Roth published by ChemistryViews magazine

Very good news for the smokers. ! Dr. Aurel