Securing Insect Eggs with Silk

Silk is a fascinating material, not just in fashion, but also in science and engineering, because the outstanding mechanical properties of these whisper-thin threads made by insects easily overshadow most man-made fibers. German researchers have now taken inspiration from the lacewing, which lays its eggs on stalks made of silk with extremely high tensile strength. As they report in the journal Angewandte Chemie, they successfully produced synthetic egg stalks from biotechnologically generated proteins modeled on an egg-stalk protein.

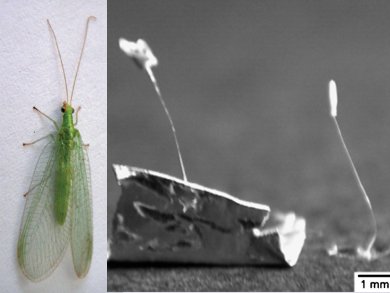

Lacewings are light-green insects with transparent wings (pictured) that are used by farmers to combat aphids. In order to protect their own offspring from predators, lacewings lay their eggs on very fine but extremely resilient silk stalks. To do this, the lacewing sticks a drop of silk dope from its abdomen to the underside of a leaf. It then presses an egg into the drop and pulls it downward. In this way, it pulls a thread that hardens within a few seconds in the air – the egg is now secured under the leaf. The threads are significantly finer than a human hair, but are so strong that they do not bend under the weight of the egg when the leaf is turned over.

The lacewing’s silk dope secretion contains several different proteins. One of the proteins contains a core domain with many repeated similar sequences. This area is flanked by small terminal domains that essentially control the properties of the silk proteins.

Synthetic Egg-Stalk Protein

Thomas Scheibel and Felix Bauer at the University of Bayreuth wanted to produce an egg stalk with properties as similar as possible to the lacewing stalks. They thus developed a synthetic egg-stalk protein made of eight repeated building blocks consisting of 48 amino acids based on the repeating units of the natural silk protein. The end units were copied exactly from the original. The researchers synthesized a gene segment that codes for this artificial protein and introduced it into bacteria that then produce the protein.

Imitating silk stalk formation, the researchers dipped tweezers into a drop of protein solution, pulled out a filament, and attached the end of the stalk to a piece of aluminum foil. After drying, the stalks had similar tensile strength and elasticity to the natural version. At higher humidity, lacewing egg stalks are superior: they can be stretched out to up to six times their original length without tearing. The reason for this is the special accordion-like structure of other silk components. The researchers are confident that they will also be able to imitate this.

Possible applications for future synthetic silks range from the vehicle construction, for example in airbags, to medical applications, such as synthetic nerve conduits or drug delivery.

- Artificial Egg Stalks Made of a Recombinantly Produced Lacewing Silk Protein,

Felix Bauer, Thomas Scheibel,

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012.

DOI: 10.1002/anie.201200591

Here are links to the future of material science.