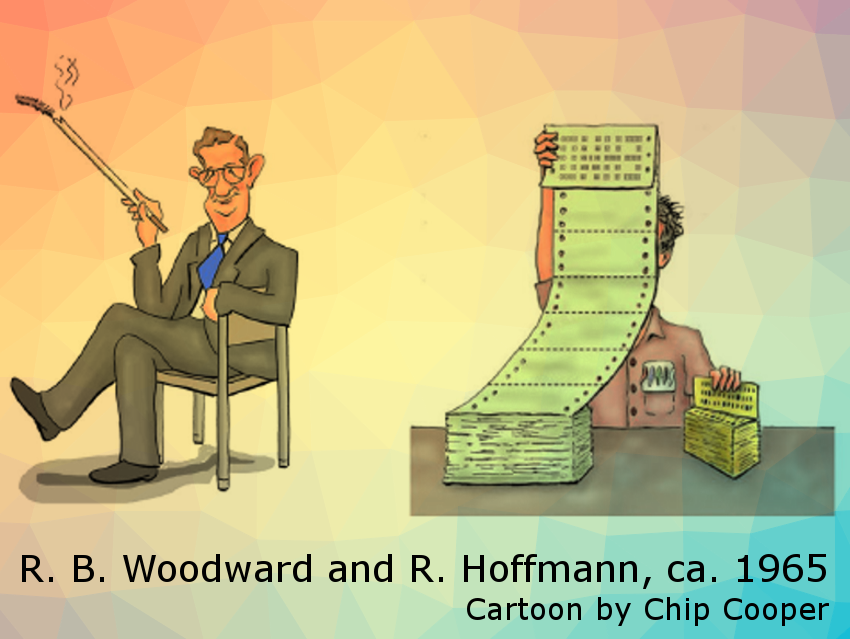

The Woodward-Hoffmann rules were first proposed by Robert B. Woodward and Roald Hoffmann in 1965. They explain and predict the ‘allowedness’ or ‘forbiddeness’ of thermal and photochemical pericyclic reactions and their stereochemical outcome.

Roald Hoffmann shared the 1981 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Fukui Kenichi “for their theories, developed independently, concerning the course of chemical reactions.” R. B. Woodward, who had already been awarded an unshared Nobel Prize in 1965 “for his outstanding achievements in the art of organic synthesis,”, had died in 1979, and was not to receive his second Nobel Prize posthumously.

The route to the Woodward-Hoffmann rules is being discussed right now in a 27-paper series in The Chemical Record – to be published every month, beginning January 2022. Center to the development of the Woodward-Hoffmann story is the human story. The series examines why it was Woodward and Hoffmann, and not any of the other chemists who were so very close to discovering the mechanism of all concerted cyclic reactions. Behind-the-scenes stories and personal dramas involving some of chemistry’s greatest chemists of the 20th century will be told. Major figures of 20th century chemistry like Kenichi Fukui, Michael Dewar, Howard Zimmermann, and H. Christopher Longuet-Higgins will come alive in their quests for knowledge and glory.

Of course, the chemistry world was shocked when E. J. Corey announced in his 2004 Priestley Medal address that Woodward had stolen his frontier molecular orbital explanation for the mechanism of electrocyclization reactions. This series will examine Corey’s claim, his relationship with Hoffmann, and the effect of this controversy on these three protagonists. Is it possibly that Corey’s allegations and Woodward’s representation as to how he came up with the idea are both truthful? How did Corey pressure Hoffmann to disavow Woodward?

Learn fascinating things about Woodward, Hoffmann, and Corey by taking the quiz:

Is This True or False?

Answers are at the very bottom of this article

![]() When Woodward and Hoffmann began their collaboration in May 1964, they had no idea that their joint research would lead to anything more than one paper.

When Woodward and Hoffmann began their collaboration in May 1964, they had no idea that their joint research would lead to anything more than one paper.

![]() Corey still believes that Woodward stole the idea from him. But Corey never discussed his claim with Woodward in the 15 years before Woodward died.

Corey still believes that Woodward stole the idea from him. But Corey never discussed his claim with Woodward in the 15 years before Woodward died.

![]() None of the first five Woodward-Hoffmann communications in JACS were peer reviewed.

None of the first five Woodward-Hoffmann communications in JACS were peer reviewed.

![]() And all five were immediately accepted for publication by the editor of JACS.

And all five were immediately accepted for publication by the editor of JACS.

![]() Roald Hoffmann turned down job offers from Caltech and University of California at Berkeley, USA, in 1962; but as Woodward and Hoffmann began publishing their papers in 1965, these universities rejected Hoffmann’s job application.

Roald Hoffmann turned down job offers from Caltech and University of California at Berkeley, USA, in 1962; but as Woodward and Hoffmann began publishing their papers in 1965, these universities rejected Hoffmann’s job application.

![]() Several chemists proposed an orbital symmetry control mechanism for cyclic concerted reactions before Woodward and Hoffmann.

Several chemists proposed an orbital symmetry control mechanism for cyclic concerted reactions before Woodward and Hoffmann.

![]() Woodward and Hoffmann hardly communicated before they began to write their first joint communication in late October or early November 1964.

Woodward and Hoffmann hardly communicated before they began to write their first joint communication in late October or early November 1964.

![]() When Woodward and Hoffmann first met to discuss a collaboration, they had met three times before. But Woodward did not remember those meetings.

When Woodward and Hoffmann first met to discuss a collaboration, they had met three times before. But Woodward did not remember those meetings.

![]() Hoffmann drafted their entire second paper by himself and placed his name first (in an era when being first author was the same as the senior author).

Hoffmann drafted their entire second paper by himself and placed his name first (in an era when being first author was the same as the senior author).

![]() The Woodward-Hoffmann collaboration began in May 1964. After completing enough extended Hückel calculations for what would be used in their first paper, Hoffmann did not think his project with Woodward was very important. Hoffmann put the project aside and worked on other projects for five months before reconnecting with Woodward. They submitted their first paper on November 30, 1964.

The Woodward-Hoffmann collaboration began in May 1964. After completing enough extended Hückel calculations for what would be used in their first paper, Hoffmann did not think his project with Woodward was very important. Hoffmann put the project aside and worked on other projects for five months before reconnecting with Woodward. They submitted their first paper on November 30, 1964.

First papers in the series:

- The Ways of Science Through the Lens of the Woodward-Hoffmann Rules. The Stories Begin,

Jeffrey I. Seeman,

The Chemical Record 2022.

https://doi.org/10.1002/tcr.202100211

- The No-Mechanism Puzzle,

Jeffrey I. Seeman,

The Chemical Record 2022.

https://doi.org/10.1002/tcr.202100212

Many of these papers will be open access

Link to the complete series

Also of Interest

- 50th Anniversary: Woodward-Hoffmann Rules,

ChemistryViews 2015. - The Woodward–Doering/Rabe–Kindler Total Synthesis of Quinine: Setting the Record Straight,

Jeffrey I. Seeman,

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007.

https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200601551 - R. B. Woodward: A Larger-than-Life Chemistry Rock Star,

Jeffrey I. Seeman,

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007.

https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201702635 - From Decades to Minutes: Steps Toward the Structure of Strychnine 1910–1948 and the Application of Todays, Technology,

Jeffrey I. Seeman, Dean J. Tantillo,

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020.

https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201916566 - The Conservation of Orbital Symmetry,

R. B. Woodward, Roald Hoffmann,

Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 1969, 8, 781–853.

https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.196907811Die Erhaltung der Orbitalsymmetrie,

R. B. Woodward, R. Hoffmann,

Angew. Chem. 1969, 81, 797–869.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.19690812102

All the statements are true.