Interstellar spectra recorded using mid-infrared spectroscopy show many emission lines. The spectral lines are usually assigned to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Indeed, PAHs are thought to be one of the main forms in which carbon exists in space. And yet, not a single member of this group of compounds had been identified in space definitively until now.

Observing a Molecular Cloud

Brett A. McGuire, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Center for Astrophysics, Harvard & Smithsonian, both Cambridge, USA, National Radio Astronomy Observatory, Charlottesville, VA, USA, and colleagues have demonstrated a way to remove the ambiguity and home in on two specific PAHs. The team used spectral matched filtering of radio data from the Green Bank Telescope to look more selectively at the emission bands from TMC-1, which is located in the interstellar Taurus Molecular Cloud.

The Taurus Molecular Cloud lies in the constellations of Taurus and Auriga and is a stellar nursery containing hundreds of newly formed stars, most aged between one and two million years. The TMC lies a mere 430 lightyears from Earth, which means we have a relatively clear view of its spectral emissions and it has, therefore, been an important region of space for studies of stellar birth and growth at all spectroscopic wavelengths.

Identifying Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Space

While the view may be clear, the spectroscopy is obfuscated. We know that the ubiquitous but unidentified emission bands are composed of features at mid-infrared wavelengths. These are characteristic of carbon–carbon and carbon–hydrogen stretching and bending in aromatic molecules and, thus, consistent with PAHs. However, while PAHs can be discerned in a mixture from their high-resolution infrared spectra in the laboratory, the differences in frequency for the interstellar spectra are smaller than the width of the bands, so this is not possible for astrochemistry.

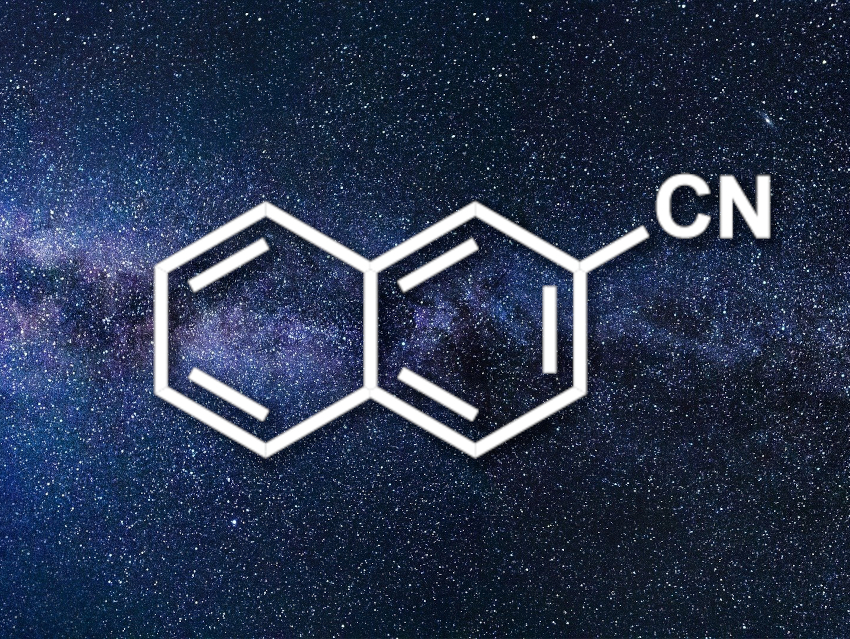

The region of TMC-1 observed by the team is currently devoid of stars and has a temperature of approximately 5–10 K. On Earth, PAHs form under much hotter conditions as byproducts of burning fossil fuels, for instance, or in the scorch marks on barbecued food. Nevertheless, in searching for the signature of a smaller, monocyclic benzonitrile molecule, the researchers have detected two PAH derivatives: 1- and 2-cyanonaphthalene (latter pictured) in the interstellar medium.

Explaining the Formation

The presence of these molecules in the interstellar medium suggests that PAHs are not simply present as sooty debris from stars, although such a “top-down” formation could be one source. These two functionalized bicyclic molecules and perhaps many others could also form from smaller organic precursor molecules in space in a “bottom-up” formation. However, known top-down or bottom-up formation reactions do not explain the abundance of the compounds. According to the researchers, either other reactions must be involved or existing formation routes could be more efficient than previously thought.

Carbon plays a critical role in the formation of planets, and PAHs may act as the seeds for processes that ultimately allow planets to form. PAHs could react and aggregate with other particles to form dust grains, which can coalesce to form bigger grains, rocks, and planets.

- Detection of two interstellar polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons via spectral matched filtering,

Brett A. McGuire, Ryan A. Loomis, Andrew M. Burkhardt, Kin Long Kelvin Lee, Christopher N. Shingledecker, Steven B. Charnley, Ilsa R. Cooke, Martin A. Cordiner, Eric Herbst, Sergei Kalenskii, Mark A. Siebert, Eric R. Willis, Ci Xue, Anthony J. Remijan, Michael C. McCarthy,

Science 2021, 371, 1265–1269.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb7535