Paul Immerwahr was born in 1866 on the Polkendorff Farm near Breslau (then in eastern Prussia, now Wojczyce, western Poland). His family was a wealthy, liberal Jewish family, which produced several chemists. He had three sisters, Elli, Rose, and Clara. His sister Clara Immerwahr (1870–1915) was the first German woman to receive a doctorate in chemistry in Germany. She was married to the Nobel Prize winner Fritz Haber. Fritz Haber, Clara and Paul Immerwahr were schoolmates.

In 1890, Paul Immerwahr completed his Ph.D. in chemistry under August Wilhelm von Hofmann in Berlin, Germany. His topic was “On the reduction of some aromatic nitriles” [1]. In 1893 he received his Ph.D. in law in Rostock, Germany. Initially he managed various paper mills, moved to Henckel-Donnersmarck’sche Vermögensverwaltung in 1904, and became Managing Director of a real estate company in Berlin in 1910. From 1912, he was Director of the Auergesellschaft in Berlin. He became Managing Director of two subsidiaries of Osram, the Chemisch-Metallurgische Industriegesellschaft and the Kälteindustrie GmbH. Before his retirement, Paul Immerwahr was Director of the insurance department of the construction office and the real estate department at Osram [3,4].

Having been ailing for a long time, he died just one year after his retirement. He was an accomplished lawyer and a chemist with a good knowledge of the latest specialist literature. His marriage with Anna Hannak remained childless [3].

Pyrethrum

As a businessman versed in chemistry, Immerwahr recognized the commercial potential of the insecticide pyrethrum, which Germany was importing from Dalmatia, at that time part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He hoped that through developing a synthesis of the active component of pyrethrum based on domestic coal tar, he could help his homeland achieve greater economic autonomy and receive a patent.

In 1910, Fritz Haber helped him find a suitable cooperation partner for this project: Hermann Staudinger. He and his Ph.D. student Leopold Ružička worked on the project in the years 1910–1916 with financial support from Paul Immerwahr.

The three agreed that Immerwahr, as financier and source of the ideas, would be the sole holder of any patents, whereas Staudinger and Ružička would be allowed to publish their scientific results after the official issuance of the patent. The series of publications became available at the beginning of 1924 [2].

Artificial Pepper

The same reasons and goals caused Immerwahr to suggest another project to Staudinger in 1915: seeking a synthetic substitute for the import-dependent pepper [3,4].

During the two world wars, it was hardly possible to import colonial goods such as coffee, tea, and tropical spices to Germany. Consequently, they became more and more expensive. Vanillin was synthetically produced since 1875 and was well received. Pepper was used in the German kitchen as a kind of universal spice besides salt and was indispensable in the food industry, especially in the production of meat and sausages.

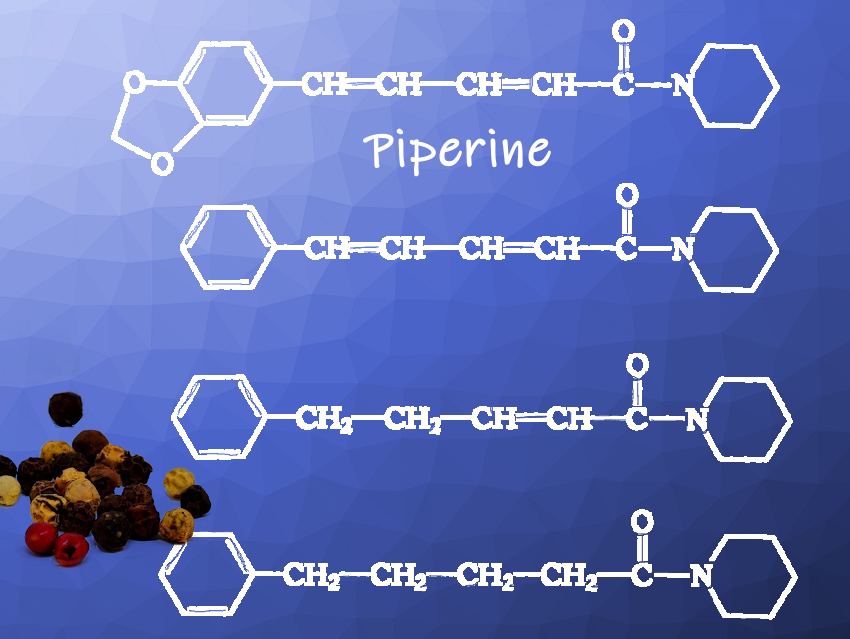

Piperine (pictured above) is the most important carrier of the pungent pepper taste and has a content in pepper fruits of 5–10 %. It is a crystalline, peppery- and pungent-tasting substance. However, essential pepper oils (2–3.5 % in black pepper and 1.8–2.9 % in white pepper), which consist of many aroma-giving compounds, also contribute to the taste of pepper.

Piperine could not be reproduced with the raw materials that were available due to the chemical management imposed during the war (difficulty to insert the methylenedioxo group). It was known that the molecule of piperine could be simplified within certain limits without losing the desired taste properties. In a methodically new approach, Staudinger had the taste of various piperine-like compounds systematically investigated.

In 1916, it was clear that three of these pungent tasting compounds (pictured above), which were given the collective name piperidides, could be produced from toluene or alternatively benzene from the light oils of coal tar distillation. Toluene or benzene was oxidized to benzaldehyde, which in turn was converted with acetaldehyde to cinnamic aldehyde. The resulting cinnamic aldehyde then had to be reacted with malonic acid to produce the peppery tasting substances.

After testing the compatibility of the three substances in animal experiments—which was necessary because they are compounds that do not occur naturally in pepper—Staudinger and Immerwahr had their synthesis realized on an industrial scale at the Rheinische Kampfer-Fabrik in Düsseldorf-Oberkassel, Germany. The availability of the respective raw materials determined which of the three compounds was produced.

The Chemische Fabrik Dr. Höhn & Cie. in Neuss am Rhein, Germany, then processed the piperidide by applying it to a matrix material to produce artificial pepper. For this purpose, small amounts of the piperidide (approx. 1.5 wt.%) were dissolved in some phellandrene, and this solution was then applied to 88.5 to 94.5 wt.% wheat bran, potato starch, or other neutral tasting, liquid-absorbing, cheap carriers and mixed. To give the artificial pepper the scent of the characteristic, extremely complex essential pepper oil, 4–10 % by weight of ground real pepper was added. The preparation was colored brown with ochre or sugar couleur.

Immerwahr managed to overcome many bureaucratic obstacles to patent the process. Surprisingly, at the turn of the years 1921/22, he transferred all rights and obligations resulting from his German and Austrian artificial pepper patent application to Staudinger. It is possible that during the years of inflation, dramatically increasing patent fees, consideration for his health, which was already under attack at the time, or personal differences with Staudinger were behind this. As a result, the synthesis of artificial pepper has so far been associated exclusively with Staudinger’s name, a view to which Staudinger probably contributed in no small way through his egocentric self-portrayals.

Although artificial spices could only survive on the market for a few years during the First and Second World Wars, the development ultimately had an enormous impact on the artificial flavor industry. Today, these processes are used in the food industry, for example, by canning and meat product factories, to conceal quality deficiencies through flavorings in cheap food. Waste products from the spice industry are used as matrix materials, for example, the pepper peelings produced in the production of white pepper, but also table salt, glucose, and lactose.

References

- Martin Freund, Paul Immerwahr, Ueber die Reduction einiger Nitrile, Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft 1890, 23(2), 2845-1858. https://doi.org/10.1002/cber.189002302198

- Klaus Roth, Elisabeth Vaupel, Pyrethrum: History of a Bio-Insecticide – Part 1, ChemViews Mag. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/chemv.201800089

- Elisabeth Vaupel, Hermann Staudinger und der Kunstpfeffer. Ersatzgewürze, Chem. Unserer Zeit 2010. https://doi.org/10.1002/ciuz.201000524

- Elisabeth Vaupel, Ersatzgewürze (1916–1948). Der Chemie-Nobelpreisträger Hermann Staudinger und der Kunstpfeffer, TG Technikgeschichte 2020. https://doi.org/10.5771/0040-117X-2011-2-91

Also of Interest

- Chemistry Advent Calendar 2020

ChemistryViews 2020.

Daily highlights from the chemistry of spices - 100th Anniversary Clara Immerwahr’s Death

ChemistryViews 2015.

A role model for her pursuit of science in spite of obstacles and for her strong moral convictions