Professor Gianluca Maria Farinola is the President of the Organic Chemistry Division of EuChemS and of the Organic Chemistry Division of the Italian Chemical Society (SCI). Here he talks to Dr. Vera Koester, ChemViews Magazine, about his fascination for organic chemistry, the value chemists bring to society, and the impulses needed from young scientists.

Why do you work for chemical societies?

My main motivation is a commitment to conveying the importance of our science and the ethical values of chemists outside our community. But at the same time, I would like to contribute to strengthening the perception of our identity as a group of scientists and professionals who develop knowledge and activities with a valuable impact on improving people’s quality of life and welfare. By this, I do not just mean to contribute to reversing the most common negative perception of chemistry, especially in Europe, as an activity which mainly threatens the environment and people’s health. Instead, and much more importantly, I would like to promote chemists’ ability to communicate to society the values that our scientific method brings: intellectual honesty, an objective and analytical approach to problems, and the rejection of rhetoric and biased positions. Such values would have a positive impact on today’s society and on politics.

I felt that it was important for me, at this stage in my personal and professional life, to take over some official roles in chemical societies. I am happy with the idea that these are non-profit organizations, with everybody involved in them contributing because they are passionate about their work. I like that a lot.

What are your goals as president of the Organic Chemistry Division of the Italian Chemical Society?

I have two main goals. The first is to increase the involvement and participation of the younger Italian organic chemists in the activities of the Italian Chemical Society and to increase their sense of belonging. It is important that they realize that they are the most important players in developing a vision of the future of chemistry in Italy.

My second main goal is to increase the participation of non-academic organic chemists in the Italian Chemical Society, people coming from companies, professional activities, teaching, or public offices. Chemical societies in my view are not only academic societies and must involve all the players in the field, regardless of their professional contexts, locations, roles, and ages.

An example of recent activities to achieve this aim occurred during the national Congress of Organic Chemistry held in Milan, Italy, last September. Assolombarda—the most important industrial association in the Lombardy region—and Confindustria—the main Italian industrial association—were actively involved in the organization of this meeting. Moreover, the conference’s last session was open to the general public, not just to registered members. It was organized together with a group of the Italian Chemical Society dedicated to the communication of chemistry led by our younger members. Overall, it was kind of a new layout for our yearly conference, which we intend to continue in the 2019 edition in Turin.

And what are your goals as president of the Division of Organic Chemistry of EuChemS?

I recently started my service in this position. I think, as the national societies’ representatives on the board do, that we should put a lot of effort into strengthening our perception of the organic chemists in Europe as a European community. Promoting our discipline and tightening our interactions and networking would, for example, allow us to have a greater impact on the politics of science on a European scale. EuChemS’ actions are becoming more and more effective, and this has to be supported by its divisions.

In this context, one of the most important activities in our division is the Young Investigator Workshop. It was promoted by the previous Presidents. Jay Siegel, Ilan Marek, Veronique Gouverneur and I consider it a key event. Every society selects one young researcher who just started their own group to participate in the two- to three-day workshop. This meeting aims at promoting and recognizing academic excellence among young researchers in organic chemistry within Europe. In addition, we invite young researchers from the US and Canada, and I plan to add more non-european young representatives, e.g., from China and Japan. The Young Investigator Workshop is establishing itself as one of the most important young investigator networking events for organic chemists worldwide.

The young representatives from each country create lasting networks. So eventually, this will result in a community of the future European academic organic chemists. Therefore, I would like to extend the participation to researchers from European companies.

So, to come back to your question, the participation of young researchers and chemists from companies is another of my main goals in my role at EuChemS.

Can you say something about your research?

My background is in synthetic organic chemistry. My research focuses on the design and synthesis of molecules, polymers, and supramolecular architectures with optoelectronic properties for applications ranging from photonics and electronics to medicine. My group is now working in two different directions: One is more classical organic synthesis, which is being applied to develop efficient routes to molecules and polymers with extended π-systems, which can be used as semiconductors in organic optoelectronics.

The second and more recent direction is the construction of bio-hybrids made up of photo-/electroactive biological nano-/microstructures with tailored organic molecules. To give one example: We have developed photonic nanostructures combining biosilica from diatoms, i.e., unicellular algae, with light-emitting molecules. Very exciting results are coming from this approach, which blends the biotechnological production of materials with organic synthesis. While placing organic chemistry center-stage, these studies require a multidisciplinary approach, which is extremely stimulating.

And what fascinates you most about this?

What fascinates me most is that we have the tools, from organic chemistry, to understand and precisely manipulate matter at the molecular level, building new assemblies finely tailored to carry out functions that will eventually lead to new materials on the macroscopic scale. We can design and synthesize new molecules, or we can isolate them from living organisms and subsequently selectively modify them, or combine them with other molecules, to create new functions. New materials are tremendously important for the future of optoelectronics, photonics, medicine, and much more. Only chemists have this molecular perception of matter, which is powerful and effective. It is also beautiful. Chemistry is the science that can build bridges between different sciences.

This is what continues to amaze me, even after twenty-five years of research in organic chemistry.

When did you create your first molecule?

During my Ph.D., I was synthesizing polyenes, molecules with many conjugated double bonds. It was the period when researchers were starting to understand the relationship between the extension of π-conjugated systems and the optoelectronic properties of those molecules. So, my supervisor, Professor Francesco Naso, challenged me to synthesize a family of stereodefined polyenes with an increasing number of conjugated trans double bonds.

I synthesized polyenes with four, six, eight, ten, twelve double bonds, all conjugated and in E configuration. When I isolated my first functionalized polyene with eight double bonds, a very difficult molecule to synthesize, as an intense red colored powder, I felt very proud. I had successfully faced up to the challenge of creating that molecule with my own hands.

What motivated you to become a chemist?

Well, I got my high school diploma from a Liceo Classico, mostly oriented to the Humanities, and including ancient Greek and Latin literature. And I was very good at that. But during that time, I also felt that my interest in physics, chemistry, and biology was maturing. So, when I had to make up my mind about my studies at the university, I had little doubt that they would be in science. I still remember some of my high school teachers were very surprised, and a bit disappointed, about my ‘twist’ towards science, and even more that my choice had been chemistry.

However, I felt motivated to study the fundamental science of matter. I wanted to understand the basic structure of matter at the deepest level within contemporary knowledge. I was in two minds about the choice between physics and chemistry. In the end, I opted for chemistry since I felt chemistry will give me not just a deep insight into the structure of matter, but also an overall conceptual framework for a proper understanding of the life sciences, while it is rooted in fundamental physics. And what I like most is that all this complex conceptual building has enormous practical applications at the same time. As I said before, I think that chemistry is a bridging science.

In retrospect, I can clearly see now that this was the right choice. Contemporary chemistry is an extraordinarily powerful and general tool to understand the world around us, interact with it, and somehow dominate it, producing goods for the progress of mankind on this planet. And after so many years in chemistry, I also feel that chemistry is a further level to perceive the beauty and perfection of Nature.

What do you do when you are not doing chemistry?

I have two teenage sons and I enjoy my time with them. I find it very interesting listening to their point of views about what happens in their lives at school or during their activities with their friends. And when they have to make decisions, I do my very best to make them feel that I am present, while trying to not affect their decisions with my opinions.

Interacting with young people and contributing to their education and inspiration is very important for me. I have the opportunity to do so with my students and with the young members of chemical societies. It is a big responsibility, but also a unique privilege, and a tremendously enriching experience.

I also like reading books a lot, especially essays, though I have much less time now for this. I like sport, particularly swimming in the sea in the summer. And traveling, which I do a lot for my work.

You have just been a visiting professor in the USA.

Yes. I have been a visiting scholar at the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Tufts University in Boston for two consecutive years in the summer, in the laboratory of Professor Fiorenzo Omenetto. Fiorenzo is a brilliant scientist and interacting with him was inspiring. We started a very interesting collaboration on the use of biological polymers as materials for many technological applications. The most stimulating results came from mixing our completely different approaches: the chemical perspective on my side with the engineering and physics perspective on his side. There are always intriguing outcomes when you combine totally different approaches in a research subject.

Previously, I had been a visiting scholar in the laboratories of Professor Luisa De Cola at the University of Münster, Germany, and then invited visiting professor at the Institut de Science et d’Ingénierie Supramoléculaires at the UNiversity of Strasbourg, France. That was also a very important time for me. I was younger and I learned a lot from Luisa’s method to value chemistry in interdisciplinary research and from her style in leading the research group and taking care of the education of her young co-workers. And I also visited the group of Professor Jean Roncali at the CNRS Laboratoire MOLTECH-Anjou at the University of Angers in France. He is a very important scientist in the field of molecular and polymeric semiconductors, and particularly one of the pioneers of the chemistry of polythiophenes.

Visiting laboratories of top-level researchers is a fundamental experience in any scientific career. My visiting researcher experiences have had a big impact on the way I do research. I plan to keep doing that in the future.

Which historic chemists do you admire?

This is not an easy question to answer. Looking at Italian chemists: Primo Levi. Of course, he is famous worldwide because he was a genius writer and authored literary masterpieces. But I want to say that I also like him as a chemist. Chemistry was his profession, and I think he perfectly describes the intellectual outlook of many chemists in their profession: a factual approach to problems, the objective collection of information, restless activity, and curiosity, often associated with a low-profile approach. This is an approach I like, and I think it is often the touch of great people: they don’t need to show off.

As for non-Italian chemists, two important people come to my mind: Gilbert N. Lewis and Linus Pauling. They gave us these incredibly important conceptual tools for understanding the fundamentals of chemistry in a very simple but effective way. For example, the Lewis theory of chemical bonding, associated with the representation of chemical structures—an elementary yet extraordinarily effective way of representing molecules using letters, lines, and dots. I am always amazed by the powerful ability of this simple stenography to represent the tremendously complex molecular world. Linus Pauling also introduced fundamental concepts which are the basis on which the entire conceptual building of structural chemistry has been set up.

And these chemists made an enormous contribution to the ethics of science and had a great impact on society. Pauling received the Nobel Peace Prize besides the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Primo Levi described in his books, with the vivid approach proper to a chemist, the brutalities of persecution in concentration camps. Both of them extended the style and principles that chemists value to convey their general cultural and political legacy.

Thank you very much for this interview.

Gianluca Maria Farinola, born 1968 in Italy, studied chemistry at the University of Bari, Italy, and was awarded his Ph.D. there in 1997. He became Assistant Professor (Ricercatore) of Organic Chemistry at the University of Bari in 1996 and then Associate Professor of Organic Chemistry from 2002 to 2015. In 2010, he gained his habilitation and a Full Professorship in Organic Chemistry from the University of Torino, Italy.

Since 2015, he has been Full Professor of Organic Chemistry at the Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro in Bari, Italy.

Gianluca Farinola serves as the President of the Division of Organic Chemistry of EuCheMS and the President of the Organic Chemistry Division of the Italian Chemical Society (SCI). From 2016 to 2018, he served as a Consultant of the Italian Parliamentary Committee and he is co-founder and member of the administrative committee of the spin-off company SYNCHIMIA s.r.l. of the University of Bari.

Gianluca Farinola’s research focuses on the design and synthesis of new multifunctional molecular, polymeric, and supramolecular photo-/electroactive organic materials for applications ranging from organic photonics and electronics to biology. His studies cover the construction and tailored chemical functionalization of molecular structures with specific optoelectronic properties, as well as the combination of active organic and organometallic molecules and polymers with biological or inorganic nanostructures, resulting in hybrid multifunctional materials with intriguing properties.

Recent investigations also focus on the use of biological polymers, for example, melanins, biosilica, and functional macromolecules (e.g., photoenzymes) from microorganisms as active materials for applications ranging from optoelectronics to biomedicine.

Selected Awards

- 2008 “Innovation in Organic Synthesis Award” of Interuniversitary Consortium CINMPIS

- 2003 “Medaglia Ciamician” of the Italian Chemical Society (SCI)

Selected Publications

- F. Milano, R. R. Tangorra, O. Hassan Omar, R. Ragni, A. Operamolla, A. Agostiano, G. M. Farinola, M. Trotta, Enhancing the Light Harvesting Capability of a Photosynthetic Reaction Center by a Tailored Molecular Fluorophore, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 11019–11023. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201203404

- G. Marzano, C. V. Ciasca, F. Babudri, G. Bianchi, A. Pellegrino, R. Po, G. M. Farinola, Organometallic approaches to conjugated polymers for plastic solar cells: from laboratory synthesis to industrial production, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 30, 6583–6614. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejoc.201402226

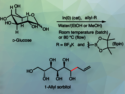

- G. Marzano, D. Kotowski, F. Babudri, A. Pellegrino, R. Musio, S. Luzzati, R. Po, G. M. Farinola, Tin-free synthesis of a ternary random copolymer for BHJ solar cells: Direct (Hetero)Arylation versus Stille Polymerization, Macromolecules 2015. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.macromol.5b01676

- A. Operamolla, A. Punzi, G. M. Farinola, Synthetic Routes to Thiol-Functionalized Organic Semiconductors for Molecular and Organic Electronics, Asian J. Org. Chem. 2017, 6, 2, 120–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajoc.201600460

- A. Punzi, I. D. Coppi, S. Matera, M.A.M. Capozzi, A.Operamolla, R. Ragni, F. Babudri, G. M. Farinola, Pd-Catalyzed Thiophene-Aryl Coupling Reaction via C-H Bond Activation in Deep Eutectic Solvents, Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 4754–4757. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02114

- R. Ragni, S.R. Cicco, D. Vona, G. M. Farinola, Multiple Routes to Smart Nanostructured Materials from Diatoms Microalgae: A Chemical Perspective, Adv. Mater. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201704289

- F. Milano, A.Punzi, R. Ragni, M. Trotta G. M. Farinola, Photonics and Optoelectronics with Bacteria: Making Materials from Photosynthetic Microorganisms, Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201805521