Fascination for d-Tubocurarine

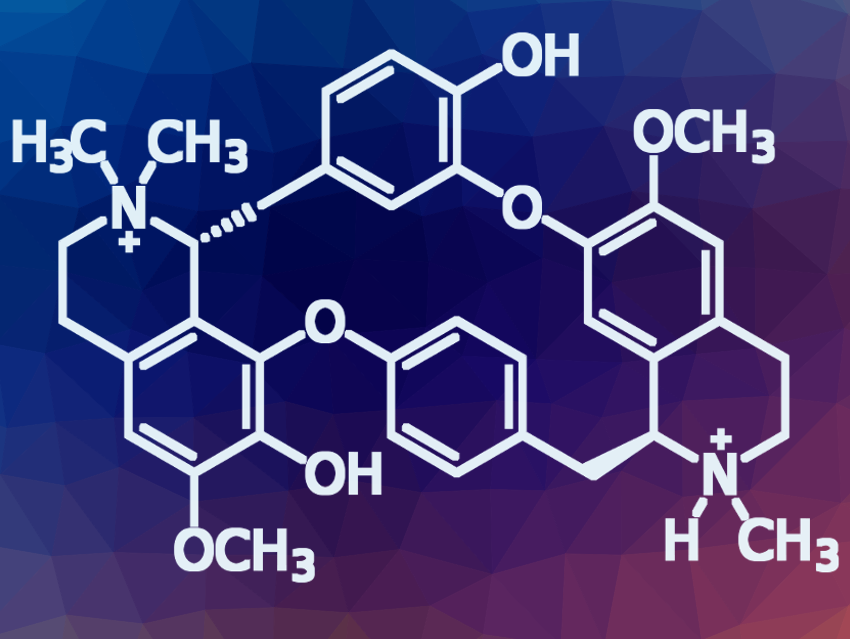

My favorite molecule is d-tubocurarine. It has an inspiring story to me, and it is also my autistic special interest. d-Tubocurarine is an active ingredient of curare, an arrow poison originally used by indigenous people in South America. It works by binding to and blocking the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors of skeletal muscles at the neuromuscular junction. For muscles to contract, acetylcholine must bind to the receptors. So blocking these receptors causes paralysis of all voluntary muscles in the body.

I first learned about this molecule when I was a teenager and read about a doctor named Scott Smith who deliberately injected himself with the poison curare to completely paralyze himself. He wanted to see how curare worked and investigate its properties firsthand. He learned that the poison did not affect thought or sensation at all, although it stopped all movement. This experiment just fascinated me. I wanted to learn all I could about the poison and learned that the main active ingredient was a molecule called d-tubocurarine.

From Poison to Medical Use

The history of curare goes back hundreds of years and is filled with curiosity and mystery. People set off to the Amazon to try to uncover the secrets of the poison, how it was made and how it worked. Over the years, it was discovered that a particular variant of the poison was made by a plant, Chondrodendron tomentosum, which contained an active molecule called d-tubocurarine that acted at the synapse between nerves and muscles to cause paralysis, and that a person could survive curare poisoning if given artificial respiration.

Figure 1. Items related to curare,

Despite originally being used to hunt and kill, d-tubocurarine later found use in medicine and has been able to save lives during surgery. Originally, if one wanted to prevent patients from moving during surgery so surgeons could perform more difficult operations, higher and more dangerous doses of anesthetics had to be used to relax the muscles. If there was a drug that selectively relaxed muscles, these difficult surgeries could be performed without the dangerous high doses of anesthetics. This was something that curare would be perfect for. In the early 1940s, doctors began using d-tubocurarine in surgery to relax muscles instead of using dangerous doses of other drugs, and it allowed for much more difficult surgeries with a much lower risk of death.

Neither Good nor Bad

It was amazing to me that something that was initially a poison could then be used to save lives. It was inspiring to see how curare’s role in the world completely changed, and it showed that whether something is “good” or “bad” is not necessarily black and white.

Before curare was used as medicine, it was feared as a deadly poison, it was used to kill, there were numerous trials and errors in treating other diseases where attempts with curare resulted in failures or dead patients, and it caused great controversy in the 1800s because of its use in vivisections, paralyzing animals while still leaving them conscious.

d-Tubocurarine could easily be seen as a terrible molecule. Yet even though it had a difficult past, it still has found its place in medicine, even if that took hundreds of years after its discovery. It pioneered the use of neuromuscular blockers in anesthesia and has helped make anesthesia a far safer area of medicine today.

That story of poison into medicine is how the interest started. And that interest became a passion. Through my own efforts to learn more about curare, d-tubocurarine, and other neuromuscular blocking drugs, I discovered my love of pharmacology, toxicology, and organic chemistry, which brought me throughout high school and into medical school.

When I would have times that I feel inadequate or I feel like a failure and my brain would want to delve into the negative self-talk, I could remind myself of the story of curare and remember that Curare was never perfect, that it started as a terrifying poison, and yet, in the end, it was able to impact the world in a positive way. Things can still change. Perceptions can change. There is always a chance to grow and improve. You do not have to be perfect to still help the world and work toward being a better person. For these reasons, d-tubocurarine, the poison that saved lives and sparked my love of molecules in the first place, has been my favorite for almost ten years.

The pictures show my desk decorated with items related to curare (see Fig. 1) and me at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) Hall of South American Peoples in New York, USA, displaying the poison darts and blowguns used to shoot curare (see. Fig. 2) wearing my d-tubocurarine molecule necklace that I had 3D printed.

Figure 2. Natalie Nakles at the AMNH Hall of South American Peoples displaying the poison darts and blowguns used to shoot curare.

Also of Interest

- Your Molecule Story

Share a molecule and why it is special to you and have the chance to win a book - Your Molecule Stories – Summary

A big thank you for your contributions: We share some highlights and congratulate the book prize winners