In his 1820 book “A Treatise on Adulteration of Food and Culinary Poisons”, Fredrick Accum (1769–1838) described how every citizen could reliably detect the worst of the common types of food adulteration by simple means. Fredrick Accum should have had a place of honor in history as a pioneer of consumer protection. But that is not how things played out.

Within a few weeks of publication of the book, his reputation was completely ruined. He lost his tremendous popularity and friends, and was driven out of England, his adopted country. His name sank into obscurity.

In this section, we will look at the book about simple methods for detecting adulterations of food – the most extensively reviewed chemistry textbook of all time – published by Fredrick Accum in 1820.

3 Chemistry Textbook About Food Adulteration

Accum’s anger about this audacity and unscrupulousness awakened the desire to warn the general public about the extent of these adulterations. This rage, coupled with his technical competence and a talent for explaining complex concepts in a way that was easil understood flowed into his most well-known work, “A Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons”.

The full title is, “A Treatise on Adulterations of Food, and Culinary Poisons, exhibiting the fraudulent Sophistications of Bread, Beer, Wine, Spiritous Liquors, Tea, Coffee, Cream, Confectionery, Vinegar, Mustards, Pepper, Cheese, Olive Oil, Pickles, and other Articles employed in domestic economy, and Methods of detecting them.”

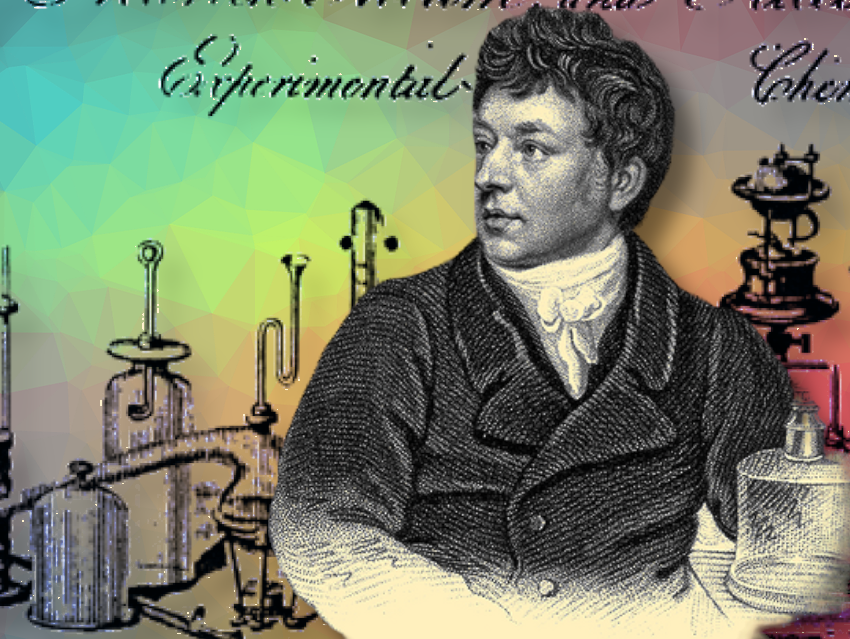

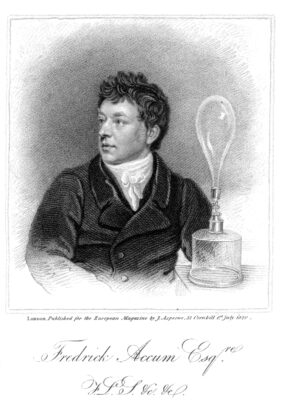

Published in 1820, this book was the first to address the topic of food adulteration and was a hit. The first edition was sold out within a month. The presses ran at full tilt and Accum’s book became the most extensively reviewed chemistry textbook of all time [6,7]. He was at the apex of his career (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Accum was honored as a pioneer of gas lighting with this engraving published in the European Magazine in 1820. (Image: Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

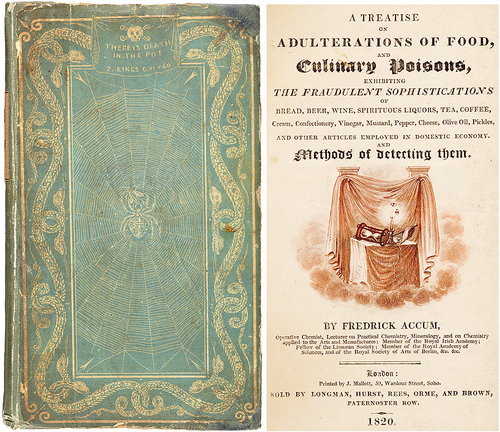

It is difficult to understand the hype without having been there. Imagine we have just arrived in London in 1820 and are lucky enough to snag a copy of Accum’s first edition. A look at the cover would shock us: twelve snakes wind around a spiderweb, the center of which is occupied by a giant spider devouring a helpless fly (see Fig. 4). This gruesome ensemble is crowned by a skull and a saying from the Old Testament of the Bible warns, “There is Death in the Pot.”

In the second book of Kings, the prophet Elisha gathered his hungry disciples and asked one of his servants to gather plants in the area to make a soup. The stew tasted bitter, and the horrified disciples cried out, “There is death in the pot.” The prophet calmed them and asked the servant to “get some flour.” The prophet added the flour to the pot and said, “Serve it to the disciples to eat.” All the bitterness had disappeared.

Figure 4. Cover and title page of the first edition of “A Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons” (1820) [8]. (Images: Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

The Bible verse listed on the book cover, “2 Kings, Chapter VI, verse 40,” is incorrect; it should be “2 Kings, Chapter IV, verse 40.” This error in the Roman numerals was corrected in the second edition.

3.1 Alarming

Right on the first page of his book, Accum makes it unmistakably clear where he’s going []:

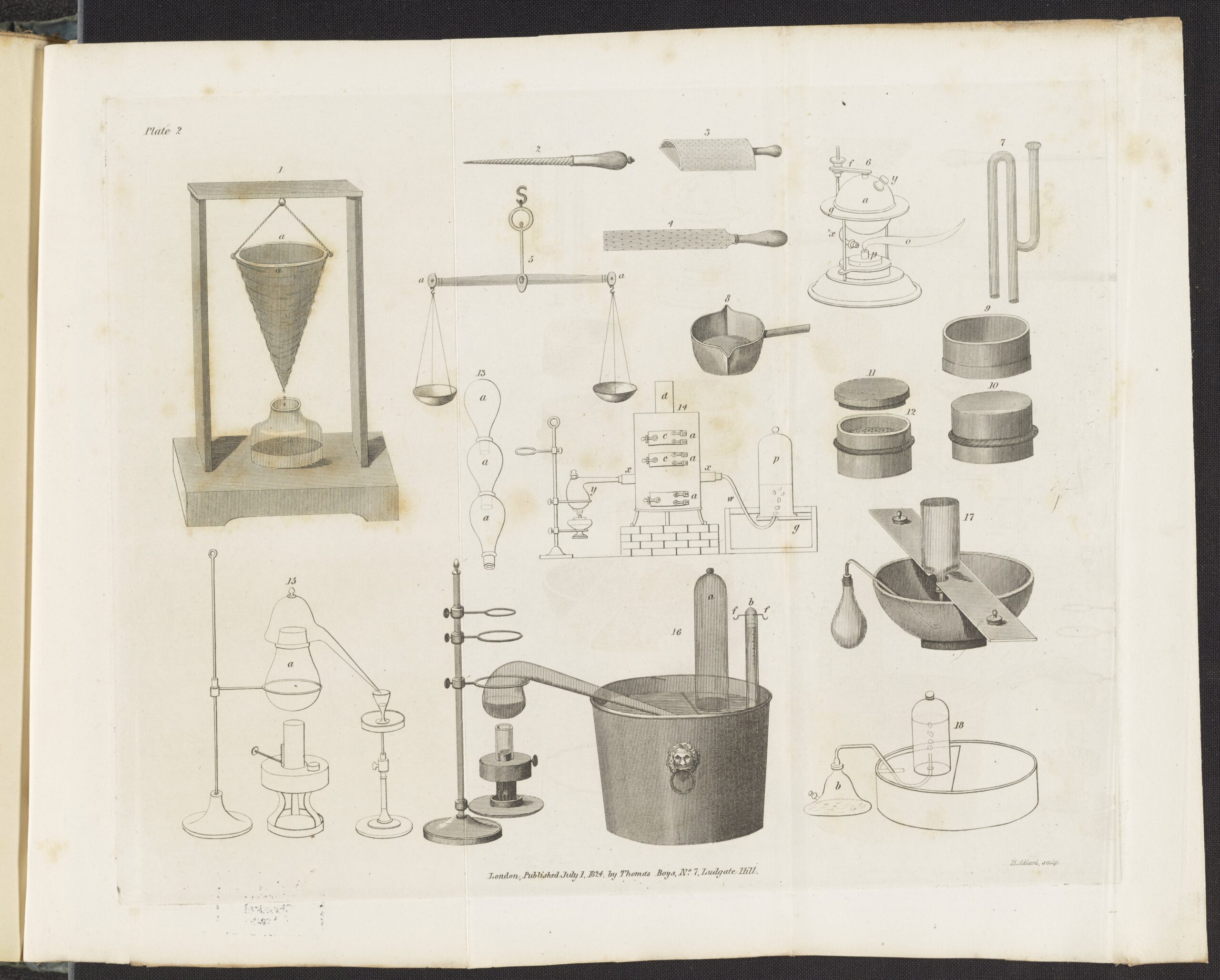

“This Treatise, as its title expresses, is intended to exhibit easy methods of detecting the fraudulent adulterations of food, and of other articles, classed either among the necessaries or luxuries of the table; and to put the unwary on their guard against the use of such commodities as are contaminated with substances deleterious to health.” (see Fig. 5)

Figure 5. Plate 2: Various chemical and pneumatic apparatuses, Engraver: Henry Adlard, of: Friedrich Christian Accum, Explanatory Dictionary of the Apparatus and Instruments Employed in the Various Operations of Philosophical and Experimental Chemistry, Boys, Thomas Shotter, London, UK, 1824. (Public Domain Mark 1.0; Courtesy of Science History Institute)

Even the most naïve of the most careless consumers in 1820 know that dilution, adulteration, and enhancement of household goods is common practice. Soap is diluted with white clay, and in paper mills, the weight of printing paper is increased by the addition of plaster. With Anglo-Saxon humor, Accum consolingly states that it could be worse, because the “The frauds committed in the tanning of skins, and in the manufacture of cutlery and jewelry, exceed belief”. Such adulterations are punishable, but “only” affect the purse. When it comes to food, the adulterations reach a whole new level, and Accum is not amused:

“But of all possible nefarious traffic and deception, practised by mercenary dealers, that of adulterating the articles intended for human food with ingredients deleterious to health, is the most criminal, and, in the mind of every honest man, must excite feelings of regret and disgust. Numerous facts are on record, of human food, contaminated with poisonous ingredients, having been vended to the public; and the annals of medicine record tragical events ensuing from the use of such food.

“The eager and insatiable thirst for gain, is proof against prohibitions and penalties; and the possible sacrifice of a fellow-creature’s life, is a secondary consideration among unprincipled dealers. … The man who robs a fellow subject of a few shillings on the high-way, is sentenced to death; while he who distributes a slow poison to a whole community, escapes unpunished.”

3.2 Introduction to the Tricks Used by Adulterators, Diluters, and Poisoners

Once Accum has riled us “careless” people up emotionally, he introduces us to the world of criminal adulterators, diluters, and poisoners:

“To such perfection of ingenuity has this system of adulterating food arrived, that spurious articles of various kinds are everywhere to be found, made up so skilfully as to baffle the discrimination of the most experienced judges.

Indeed, it would be difficult to mention a single article of food which is not to be met with in an adulterated state; and there are some substances which are scarcely ever to be procured genuine.”

Accum shows how the most important foods can be adulterated. And the list of additives is long, ranging from water for the dilution of beer, wine, or milk, to highly toxic heavy metal compounds used to enhance confections and liquor.

In addition to simply informing us about the issue, Accum develops tests for the detection of adulterations, “In stating the experimental proceedings necessary for the detection of the frauds which it has been my object to expose, I have confined myself to the task of pointing out such operations only as may be performed by persons unacquainted with chemical science; and it has been my purpose to express all necessary rules and instructions in the plainest language, divested of those recondite terms of science, which would be out of place in a work intended for general perusal.“

Some examples:

3.2.1 Vinegar

Vinegar is normally obtained through the fermentation of malt or wine. It should be pale brown, completely transparent and aromatic, with a pleasant, somewhat pungent taste.

In 1820, vinegar is often adulterated by dilution with water and the addition of sulfuric acid to increase acidity. This is not a health hazard, but is a fraud, and consumers are warned by Accum and provided with the appropriate test:

Detection of sulfuric acid in vinegar:

“The presence of this acid is detected, if, on the addition of a solution of acetate of barytes, a white precipitate is formed …” This is a classic reaction for the detection of sulfate ions. After addition of barium acetate to a solution containing sulfate ions, barium sulfate, which has low solubility, precipitates out as a white solid. SO42–+ Ba2+ →BaSO4↓

This should be sufficient for filing a claim, but in practice, identification of a vinegar counterfeiter is difficult, because the merchants are not the producers, and the entire chain of processing chain would have to be traced back to the source.

3.2.2 Pickles

This British specialty consists of diced vegetables (cucumbers, bell peppers, green beans, cauliflower, etc.) that have been covered in hot vinegar and placed in jars. Because the vegetables get paler over time, copper salts are added for color. The toxicity of these compounds is well known by about 1800, as the English physician Dr. Thomas Percival strikingly reported about the fatal poisoning of a seventeen- year-old woman in 1783 [9]:

“A young lady who amused herself, while her hair was dressing, with eating samphire pickles impregnated with copper. She soon complained of pain in the stomach; and, in five days, vomiting commenced, which was incessant for two days. After this, her stomach became prodigiously distended; and, in nine days after eating the pickles, death relieved her from her suffering.”

Sea fennel (Crithmum maritimum, rock samphire, or samphire) is a 10–50 cm high member of the carrot family that grows within range of the sea spray on the rocky shores of the Mediterranean Sea and Eastern Atlantic as far as Northern Ireland and Scotland. It can be used in salads and is an aromatic side dish in Majorcan cuisine.

This knowledge about the toxicity of copper has not penetrated into the culinary arts or households of this time. It is shocking how the recipes popular around 1800 often called for the direct addition of copper salts or required extremely long, close contact with the hot surfaces of copper pots and pans. Accum warns us not to rely on traditional recipes, but to scrutinize them critically, urgently advising that all copper surfaces of cookware should be plated with tin.

As for recipes containing copper salts, Accum names the journals and cookbooks in which thoughtless authors copy ancient recipes over and over. Here are three terrifying examples:

The Ladies’ Library: “To Pickle Gerkins”

“Boil the vinegar in a bell-metal or copper pot; pour it boiling hot on our cucumbers.”

Bell metal (bronze) is a copper-tin alloy. In the presence of oxygen in air, copper is oxidized, and the vinegar takes on the blue-green color of copper acetate. 2 Cu + O2 + 4 CH3COOH → 2 Cu(CH3COO)2 + 2 H2O

Modern Cookery, or the English Housewife: “To Make Greening”

“Take a bit of verdigris, the bigness of a hazel-nut, finely powdered; half-a-pint of distilled vinegar,and a bit of alum powder, with a little bay salt. Put all in a bottle, shake it, and let it stand till clear. Put a small tea-spoonful into codlings, or whatever you wish to green.”

One British pint = 568 mL. This reaction forms verdigris, a basic copper acetate that has antimicrobial activity and is toxic.

The English Housekeeper: “To Render Pickles Green”

“To render pickles green, boil them with halfpence, or allow them to stand for twenty-four hours in copper or brass pans.”

All three of these recipes lead to life-threatening poisoning. The boiling of a copper-containing coin in an acidic brew particularly makes us shudder, because Dr. Thomas Percival has already described what happens:

“A small boy swallowed a halfpenny coin. The next day he could not take any more food into his stomach. He vomited large quantities of a green liquid that smelled of verdigris. As the symptoms slowly subsided, he was persuaded to eat solid food and to partake of physical exercise by day. In the evening, the youth was given an enema, after which the coin was excreted.”

For his anxious readers, Accum provides a test for the easy detection of copper in pickles and other foods:

Detection of copper in pickles:

“To detect the presence of copper, it is only necessary to mince the pickles, and to pour liquid ammonia, diluted with an equal bulk of water, over them in a stopped phial: if the pickles contain the minutest quantity of copper, the ammonia assumes a blue colour.”

Liquid ammonia is ammonia (NH3) dissolved in water (ammonium hydroxide); Cu2+ (pale blue) + 4 NH3 → [Cu (NH3)4]2+ (deep blue)

3.2.3 Tea and Coffee

Both of these high-priced foods are often adulterated. In the case of tea, similar-looking leaves of local native plants are primarily used:

“Various persons often dye and prepare very large quantities of sloe leaves and previously used tea leaves or leaves from other trees, bushes or plants into an imitation of tea. They sold this as genuine tea.”

Accum also discovers that most of the green teas he examines are adulterated with copper carbonate to intensify the green color of the tea after brewing. This adulteration is easy to detect by using the copper test given for pickles.

Analysis of roasted and ground coffee pushed the analytical chemistry of 1820 to its limits, as most adulteration involved the use of foreign plant materials. Accum comforts his readers with Anglo-Saxon humor:

“The adulteration of ground coffee, with pease and beans, is beyond the reach of chemical analysis; but it may, perhaps, not be amiss on this occasion to give to our readers a piece of advice given by a retired grocer to a friend, at no distant period:—”Never, my good fellow,” he said, “purchase from a grocer any thing which passes through his mill. You know not what you get instead of the article you expect to receive—coffee, pepper, and all-spice, are all mixed with substances which detract from their own natural qualities.”—Persons keeping mills of their own can at all times prevent these impositions.”

The fact that we can use our own senses to judge aromatic beverages like tea and coffee was proven by the High Court in 1818 in the case of “The King against Brady”. In this trial, grocer Alexander Brady was charged with having sold a sham coffee powder consisting mainly of ground, roasted peas and beans with a small amount of coffee, as genuine coffee.

“One of the commissioners tasted some of the eighteen pounds of sham-coffee produced by the officers, and declared that it was a most infamous stuff, and unfit for human food.

Defendant.—’Why, I have sold it for twenty years.’

Commissioner.—’Then you have been for twenty years acting most dishonestly, defrauding the revenue; and the health of the poor must have suffered very much by taking such an unwholesome article. Your having dealt in this article so long aggravates your case; you have for twenty years been selling burnt beans and pease for genuine coffee.—You are convicted in the penalty of 50£.’”

The purchasing power of the British pound sterling in 1820 corresponds to about 6,200 pounds today [10].

3.4 Beer

In his most comprehensive chapter, Accum covers the adulteration of beer.

“Malt liquors, and particularly porter, the favourite beverage of the inhabitants of London, and of other large towns, is amongst those articles, in the manufacture of which the greatest frauds are frequently committed. The statute prohibits the brewer from using any ingredients in his brewings, except malt and hops; but it too often happens that those who suppose they are drinking a nutritious beverage, made of these ingredients only, are entirely deceived.”

Beer is adulterated at all stages of production. From the partial replacement of malt and hops – the only legal ingredients — with substitutes, to addition of forbidden dyes and bitters and finally dilution and blending at the bar. There was substitution, cheating, tricking, and poisoning – the list of legally forbidden additives is long.

Below is a small selection:

Fishberry is used in place of malt and hops; they prevent a second fermentation of the bottled beer. Their effect is intoxicating.

Fishberries are the dried, 1 cm fruit of the Fishberry (Indian berry, Levant nut, Anamirta cocculus), a climbing plant native to Southeast Asia. The pharmacological activity of its bitter ingredients is similar to strychnine. Ingestion of 2–3 g of berries is a lethal dose for humans.

Calamus is used in brewing as a substitute for hops and to increase their intensity; one pound of calamus is equivalent to about six pounds of hops.

Calamus (sweet flag, sway, muskrat root, Acorus calamus) is native to Asia and was introduced to Central Europe in the 16th century. The root is used as a traditional medicine, flavoring, and tea, as well as being a typical ingredient in digestive bitters.

Quassia “leaves a bitter taste in the mouth, long after the beer has been consumed.”

Quassia (Quassia amara) is a tree native to South America. Its wood is used as a bitter in traditional medicine. Because of its extreme bitterness a quassia tincture can be painted on fingers to discourage fingernail chewing. Quassia is also an ingredient in bitter liquors.

Beans are used to give malt beverages a mellow flavor.

Oyster shells are very useful in mellowing sour beer; however, the barrel must not be fully closed once they are added.

Alum (potassium aluminum sulfate) is consistently added to vats because it gives the beer an aged flavor.

Vitriol of Iron “(Iron sulfate) lends porter a foaming quality when it is poured out of one vessel into another, a beer-heading agent, commonly comprised of green vitriol (iron sulfate), alum, and salt. This addition to the beer is usually made by the publicans.”

The scale of the adulterations is so immense that it is barely believable. Accum felt compelled to record not only the deeds, but also the names of the convicted offenders and legally condemned perpetrators (see Extra Info below).

In doing this he was conscious that such exposures are problematic:

“However invidious the office may appear, and however painful the duty may be, of exposing the names of individuals, who have been convicted of adulterating food; yet it was necessary, for the verification of my statement, that cases should be adduced in their support; and I have carefully avoided citing any, except those which are authenticated in Parliamentary documents and other public records.”

Extra Info: Examples of prosecuted and convicted London druggists, grocers, brewers, and publicans, and their crimes and penalties from the early 1800s

See answer

Druggists and Grocers

Druggists and grocers who supplied illegal ingredients to brewers for adulterating beer between 1812 and 1819:

- John Dunn and another, druggists, for selling adulterating ingredients to brewers, verdict 500 pounds.

- Whitcombe, Dunn, and Waller, druggists, for having liquor for darkening the color of beer, hid and concealed.

- T. Renton, grocer, for selling molasses to a brewer, loss of license.

Brewers

Brewers prosecuted and convicted from 1813 to 1819 for receiving and using illegal ingredients in their brewings:

- Ing, brewer, using Cocculus india, hard coloring, and honey, dead.

- Blake and others, brewers, for using adulterating ingredients, and mixing strong and table beer, 250 pounds.

- Moore, brewer, for using coloring, 300 pounds

- Webb and Ball, for using ginger, Guinea pepper, and brown powder (name unknown), first 100 pounds. Second 500 pounds.

- Clarke, for using molasses, 150 pounds.

- Swain and Sewell, for using Cocculus india, Guinea opium, etc., 200 pounds.

- Mitchell, for using Cocculus india, vitriol, and guinea pepper, left the country.

- Gray, for using ginger, hartshorn shavings, and molasses, 300 pounds.

- Lane, brewer, for using wormwood instead of hops, 5 pounds.

Publicans

Publicans prosecuted and convicted from 1815 to 1818, for adulterating beer with illegal ingredients, and for mixing table beer with their strong beer.

- Harris, for using salt of steel, salt, molasses, etc., and for receiving stale beer and mixing it with strong beer; 42 pounds

- Dean, for using salt of steel, salt, molasses, etc., and for mixing table beer with strong beer; 50 pounds.

3.2.5 Wine

Like beer, everything you could think of to increase profit has also been added to wine. Among the most dangerous additives was the sweet-tasting compound called lead sugar (lead acetate, Pb(CH3COO)2).

“The most dangerous adulteration of wine is by some preparations of lead, which possess the property of stopping the progress of acescence of wine, and also of rendering white wines, when muddy, transparent … Wine merchants persuade themselves that the minute quantity of lead employed for that purpose is perfectly harmless, and that no atom of lead remains in the wine. Chemical analysis proves the contrary; and the practice of clarifying spoiled white wines by means of lead, must be pronounced as highly deleterious.

Lead, in whatever state it be taken into the stomach, occasions terrible diseases; and wine, adulterated with the minutest quantity of it, becomes a slow poison … If to debase the current [Pg 83]coin of the realm be denounced as a capital offence, what punishment should be awarded against a practice which converts into poison a liquor used for sacred purposes.”

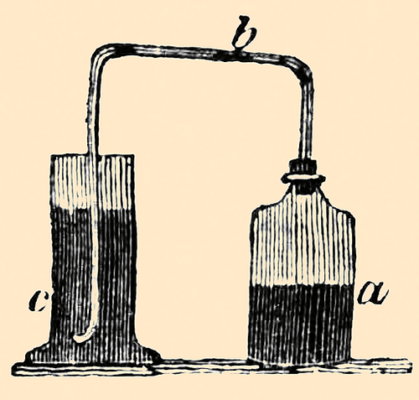

The minutest quantities of lead can be detected by the “wine test”, in which the required water saturated with hydrogen sulfide can be prepared at home by the following procedure.

Figure 6. Diagram for the preparation of water saturated with hydrogen sulfide (Image: Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

Production of Water Saturated with Hydrogen Sulfide

See Figure 6. “Take a bottle (a) or Florence flask, adapt to the mouth of it a cork furnished with a glass tube (b), bent at right angles; let one leg of the tube be immersed in the vial (c) containing the water to be examined.

“Then take one part of sulphuret of antimony of commerce, break it into pieces of half the size of split pease, put it into the flask, and [Pg 71]pour upon it four parts of common concentrated muriatic acid (spirit of salt of commerce). Sulphuretted hydrogen gas will become disengaged from the materials in abundance, and pass through the water in the vial (c). Let the extrication of the gas be continued for about five minutes.”

Hydrogen sulfide is a highly toxic gas. We can detect very low concentrations of this gas by its characteristic rotten egg odor. To estimate the amounts used in this process, we assume a pea-sized piece (d = 8 mm) to be 1 g of antimony sulfide Sb2S3 (M = 2340 g/mol; 72 % Sb, 28 % S, density 4.5).

Full conversion (Sb2S3 + 6 H+ → 3 H2S + 2 Sb3+) would produce 0.28 g of gaseous hydrogen sulfide. If the vial contains 100 mL water, it can hold 0.4 g of dissolved hydrogen sulfide, which is significantly more than is produced by the reaction.

“The wine test consists of water saturated with sulphuretted hydrogen gas, acidulated with muriatic acid. By adding one part of it, to two of wine, or any other liquid suspected to contain lead, a dark coloured or black precipitate will fall down, which does not disappear by an addition of muriatic acid …

The action of the sulphuretted hydrogen test, when applied in this manner, is astonishingly great; for one part of acetate of lead may be detected by means of it, in 20,000 parts of water.”

Pb(CH3COO)2 + H2S → PbSi + 2 CH3COOH; with a solubility product of L = 10–30 [mol2/L2], lead sulfide is extraordinarily insoluble.

Sulphuret of antimony (antimony (III) sulfide) is a shiny mineral with the molecular formula Sb2S3.

3.2.6 Lead in Olive Oil and Cheese

With slight modifications, the “wine test” can be used to test all foods for adulteration with lead. This caused Accum to come across some surprises:

Around 1800, Spanish olive oil often contains lead because it is stored in lead containers. Accum recommends olive oil from Italy and France, because lead containers are usually not used there.

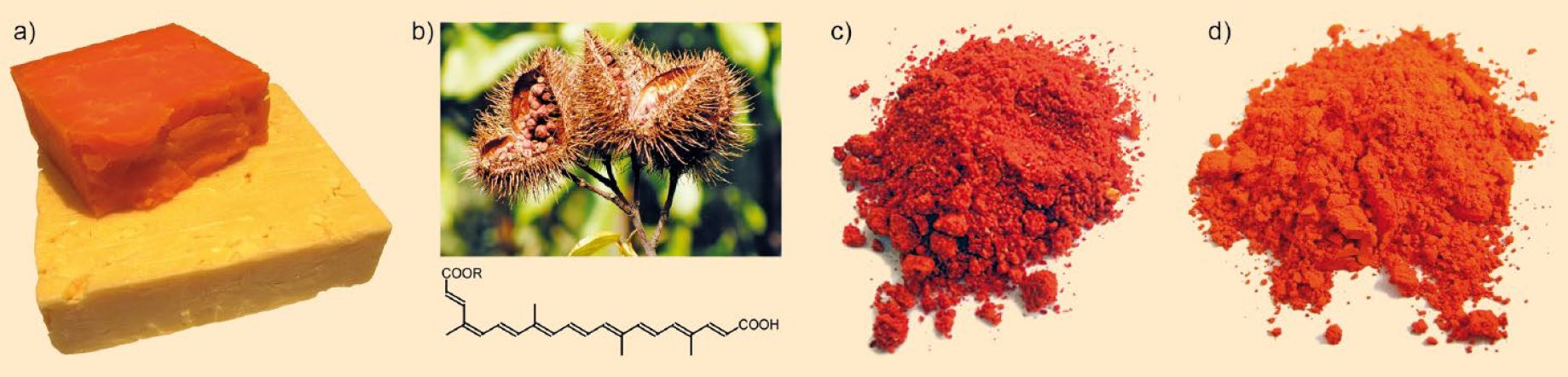

The curious means by which lead can end up in Gloucester cheese are demonstrated by Accum’s tests on various samples of this specialty of southern England, which is colored with annatto, like the better-known cheddar (see Fig. 7).

Deep red annatto dye is made from the seeds of the achiote shrub (Bixa Orellana), which is native to the tropical regions of America. Today, this dye is approved for use as a food additive in the EU (E 160b). Chemically, annatto is a mixture of bixin and norbixin.

Figure 7. The color of Gloucester cheese. a) 12 months aged without (bottom) and with (top) annatto coloring; b) Opened fruits with the red seeds of the annatto tree, main components: Bixin, R = -CH3 and Norbixin, R = -H; c) Vermilion = mercury sulfide, HgS; d) Red lead = lead(II,III) oxide, Pb3O4.

(Images: a) GeoTrinity, Wikimedia Commons, CC 3.0; b) Rigues, Wikimedia Commons, CC 3.0; c) Vermilion, Wikimedia Commons, Kardinal9, CC 3.0; d) Red lead, Wikimedia Commons, BXXXD, CC 3.0)

When seed shipments from America were paused or only poor color quality was available in London, producers added cinnabar, which is relatively harmless when taken orally in small quantities because of its extremely low solubility. They also added red lead, a highly toxic compound. Here is the whole story:

“A gentleman, who had occasion to reside for some time in a city in the West of England, was one night seized with a distressing but indescribable pain in the region of the abdomen and of the stomach, accompanied with a feeling of tension, which occasioned much restlessness, anxiety, and repugnance to food. He attributed his illness to a plate of toasted Gloucester cheese, of which he had partaken heartily. The circumstance was mentioned to the mistress of the inn, who expressed great surprise, as the cheese in question was not purchased from a country dealer, but from a highly respectable shop in London.

“On subsequent inquiries, through a circuitous channel, unnecessary to be detailed here at length, on the part of the manufacturer of the cheese, it was found, that as the supplies of anotta had been defective and of inferior quality, recourse had been had to the expedient of colouring the commodity with vermilion [cinnabar]. Even this admixture could not be considered deleterious.

“But on further application being made to the druggist who sold the article, the answer was, that the vermilion had been mixed with a portion of red lead; and the deception was held to be perfectly innocent, as frequently practised on the supposition, that the vermilion would be used only as a pigment for house-painting.

“Thus the druggist sold his vermilion in the regular way of trade, adulterated with red lead to increase his profit, without any suspicion of the use to which it would be applied; and the purchaser who adulterated the anotta, presuming that the vermilion was genuine, had no hesitation in heightening the colour of his spurious anotta with so harmless an adjunct.

“Thus, through the circuitous and diversified operations of commerce, a portion of deadly poison may find admission into the necessaries of life, in a way which can attach no criminality to the parties through whose hands it has successively passed.”

3.2.7 Children’s Toys

Accum’s A Treatise on Adulterations of Food reveals the criminal food adulteration occurring in London around 1820 to a broad audience. For the most dangerous adulterations involving copper and lead compounds, he develops experiments every citizen can use to detect highly toxic heavy metals in their own food. In the last section of A Treatise on Adulterations of Food, Accum justifies the necessity of his thoroughness.

“When we consider the various unsuspected means by which the poisons of lead and copper gain admittance into the human body, a very common but dangerous instance presents itself: namely, the practice of painting toys, made for the amusement of children, with poisonous substances, viz. red lead, verdigris, &c.

[Editor’s comment: “viz.” (short for videlicet) means “namely” or “that is to say.” “&c.” (short for et cetera) means “and so forth” or “and others.”]

Children are apt to put every thing, especially what gives them pleasure, into their mouths; the painting of toys with colouring substances that are poisonous, ought therefore to be abolished; a practice which lies the more open to censure, as it is of no real utility.”

The book is a huge hit. The first edition was sold out within a month. The second edition is produced three months after the first and is sold out within a week. The reasons for which Fredrick Accum did not become a pioneer in consumer protection with this 1820 book about simple methods for detecting food adulteration are the subject of the next part of this article.

References

[6] C. A. Browne, Recently Acquired Information concerning Fredrick Accum, 1769-1838, Chymia 1948, 1, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.2307/27757110

[7] Accum included some reviews in his 1821 book “Culinary Chemistry”: The Project Gutenberg EBook of Culinary Chemistry, by Frederick Accum, 2019. EBook #60163

[8] Friedrich Accum, A treatise on adulterations of food, and culinary poisons, London, UK, 1820.

[9] T. Percival, Med. Trans. Coll Physicians 1783, III, 80. Reprint in: The Works, Literary, Moral, and Writings of Thomas Percival, M. D., Cambridge Library Collection, Hist. Med. 2013, 221, Cambridge University Press, UK. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107360679

[10] Value of £1 from 1820 to 2024, CPI Inflation Calculator. (accessed January 2024)

The article has been published in German as:

- Aufstieg und Fall des Fredrick Accum: Da ist der Tod im Topf,

Klaus Roth,

Chem. unserer Zeit 2024, 58(3), 156-168.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ciuz.202300034

and was translated by Caroll Pohl-Ferry.

Death in a Pot: From England’s Famous Chemist to Exiled and Forgotten – Part 1

Why did Fredrick Accum’s 1820 book about simple methods for detecting the adulteration of foods not make him a pioneer of consumer protection?

Death in a Pot: From England’s Famous Chemist to Exiled and Forgotten – Part 3

From the tragic case of Fredrick Accum, the significance of his work to this day, and the current state of food adulteration

See similar articles by Klaus Roth published on ChemistryViews.org