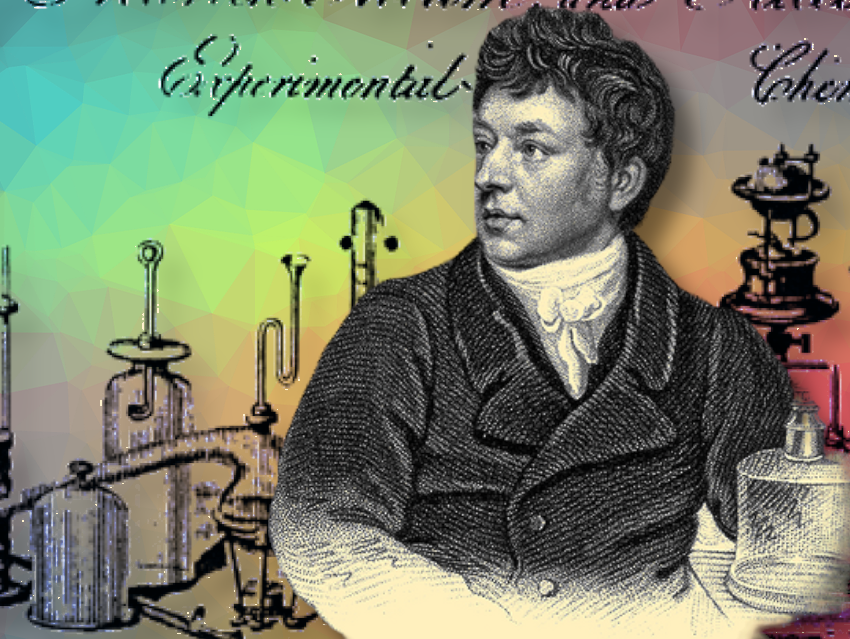

In his 1820 book “A Treatise on Adulteration of Food and Culinary Poisons”, Fredrick Accum (1769–1838) described how every citizen could reliably detect the worst of the common types of food adulteration by simple means. Fredrick Accum should have had a place of honor in history as a pioneer of consumer protection. But that is now how things played out.

Within a few weeks of publication of the book, his reputation was completely ruined. He lost his tremendous popularity and friends, and was driven out of England, his adopted country. His name sank into obscurity.

Why did this happen?

1 Who Was Fredrick Accum?

Friedrich Accum was born in 1769 to an affluent soap maker in Bückeburg, Westphalia, Germany. After graduating from school, Friedrich began an apprenticeship in a pharmacy run by the Brande Family in Hannover. As apothecaries to the English King George III, the Brandes also operated a pharmacy in Arlington Street in London, UK [1].

George III (George William Frederick) (1738–1820) descended from the House of Hannover and from 1760 reigned as King of Great Britain and Ireland as well as Elector of Braunschweig-Lüneburg. After the Vienna Congress of 1814, he was also King of Hannover.

Friedrich began working in the Brandes’ London pharmacy in 1793, studying at the Hunterian Anatomy School in his free time. This is where his steep ascent to being the most famous chemist of early 19th century England began — as outlined below.

1.1 The Rise of Fredrick Accum

1798: Accum published his first scientific work, “On the Light Emitted by Supersaturated Borate of Soda, or Common Borax”, in the Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts. He used the anglicized version of his name, Frederick, which he later changed to Fredrick.

1798: He married Mary Ann Simpson (1777–1816), who bore eight children, only two of whom survived childhood.

1800: Accum moved to Old Compton Street 11 in London, where he gave private lessons and took in students as boarders. For many years, his laboratory was the most important English institution for learning chemical laboratory practice.

1801: Accum was appointed Assistant Chemical Operator at the Royal Institution of Great Britain under Director Humphry Davy. He developed chemical demonstrations that were presented in popular evening lectures. These lectures were so popular that Albemarle Street, where the Royal Institution was located, was made the first one-way street in London in an attempt to ease the heavy coach traffic they generated.

1803: Accum left the Royal Institution to trade in laboratory equipment and chemicals. He built experiment kits that laypeople could use to carry out harmless chemical experiments at home and wrote the instructions for them. In addition, he was the successful author of several natural science textbooks that were aimed at the general public.

1803: His “System of Theoretical and Practical Chemistry” was published. It was the first English language textbook based on the findings of Antoine Lavoisier.

1808: In Philosophical Magazine, Accum published the results of his chemical analyses of mineral waters.

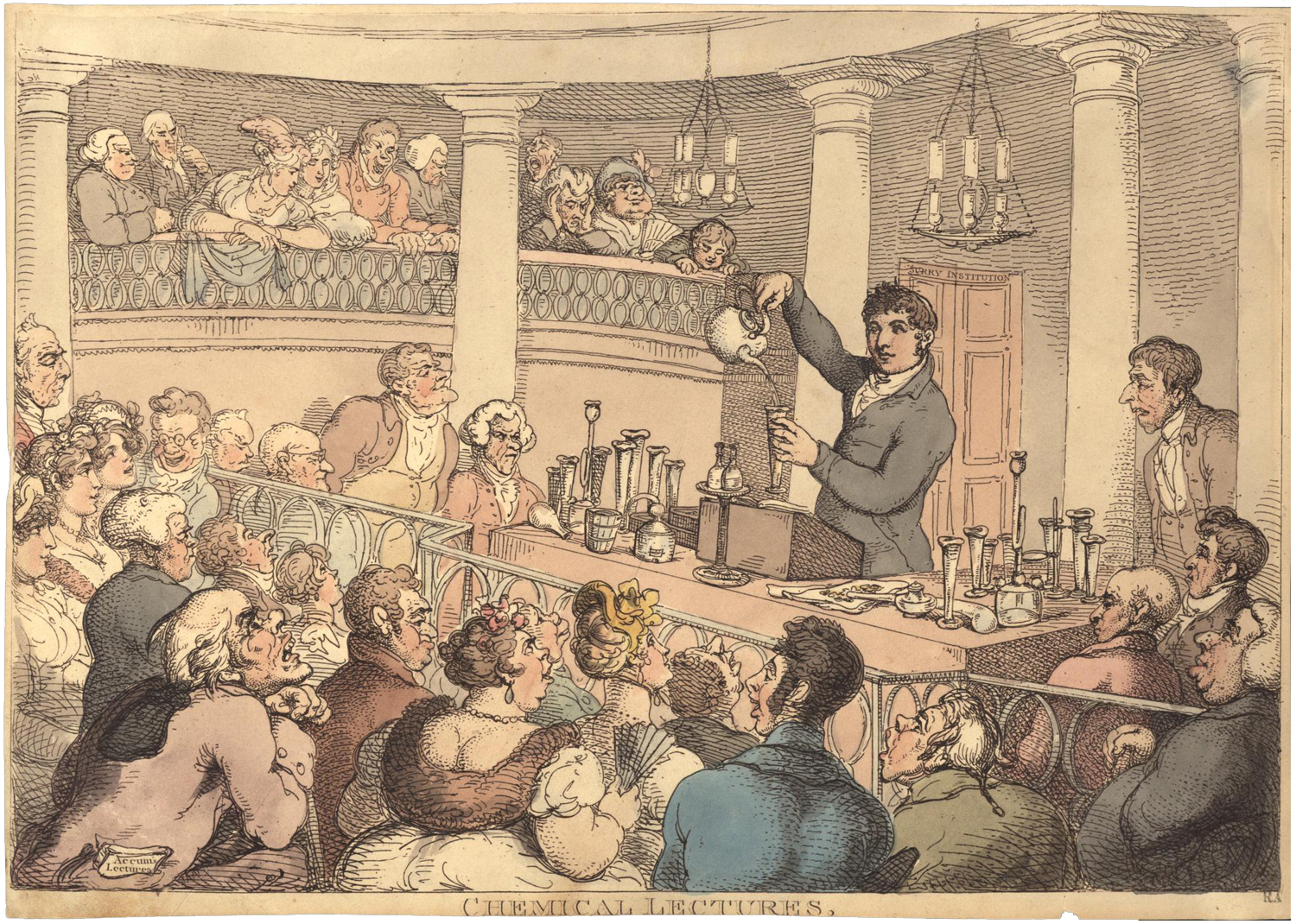

1809: Accum was appointed Professor of Chemistry at the Surrey Institution, whose goal was to promote and popularize the natural sciences. His assignment was to “initiate into the principles of chemical philosophy those, who possess no previous knowledge of it” [2]. His public lectures (Accum’s lectures) took place in the Rotunda on Wednesdays around 7:00 in the evening and were social events (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Accum’s Lectures. This 1809 caricature depicts illustrious members of the public yawning and paying little attention in the first row. A program entitled “Accum’s Lectures” protrudes from the right jacket pocket of an elderly audience member in the lower left corner. (Image: Wikimedia commons, public domain)

1810: On behalf of the Chartered Gaslight and Coke Company, Accum carried out numerous studies about the safe production and use of gas for lighting.

1812: Accum was appointed to the board of directors of the Chartered Gaslight and Coke Company.

1813: “Elements of Crystallography after the Method of Haüy”

1815: “A Practical Treatise on Gaslight”

1817: “Chemical Amusement, Comprising a Series of ―Curious and Instructive Experiments in Chemistry: Which are Easily Performed, and Unattended by Danger”. This printing was sold out within two months.

1.2 Versatile, Competent, and Pedagogically Talented Chemist

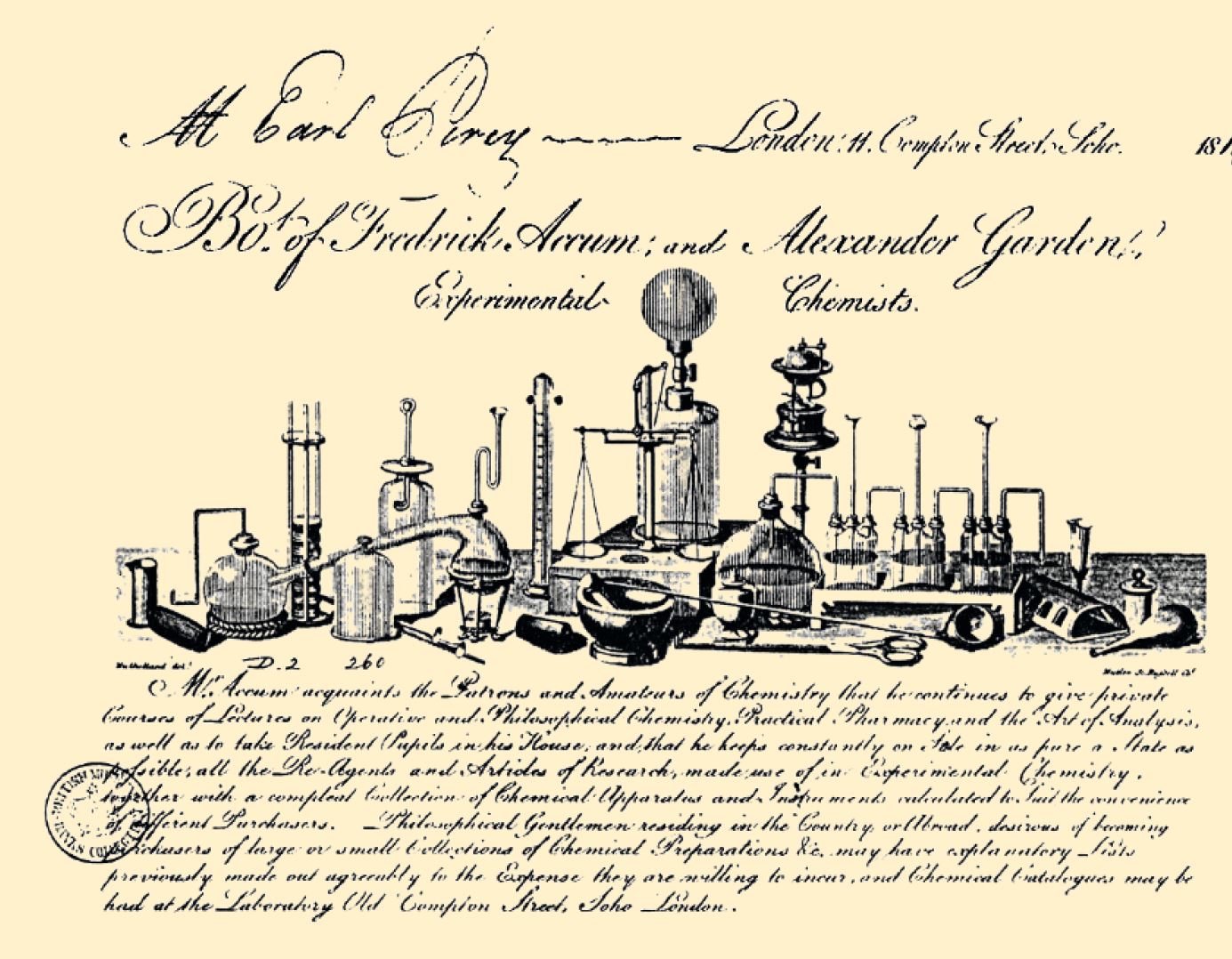

This excerpt from his work demonstrates that Fredrick Accum was a versatile, competent, and pedagogically talented chemist (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Accum’s professional card.

On this card, Accum presented himself as the multitalented person he truly was: “Mr. Accum acquaints the Patrons and Amateurs of Chemistry that he continues to give private Courses of Lectures on Operative and Philosophical Chemistry, Practical Pharmacy and the Art of Analysis, as well as to take Resident Pupils in his House, and that he keeps constantly on sale in as pure a state as possible, all the Re-Agents and Articles of Research made use of in Experimental Chemistry, together with a complete Collection of Chemical Apparatus and Instruments calculated to Suit the conveniences of Different Purchasers.” [3]

(Image: Wikimedia commons, public domain)

He was not an academic engaged in basic research; his studies always came back to practical applications intended to lead to immediate improvements in living conditions. He thus used the new chemical analytical methods of the time to determine the purity of foods and medications. Within a short time, he gained a reputation among both professionals and laypeople as a valued expert and consultant in this field.

2 Dark Blue Tea

The following case involving a large amount of poisoned tea was brought before Accum in 1819 and caused a huge stir in newspapers and journals [4,5]:

“A London char-woman having purchased an ounce of green tea, was struck by the lively blue color which the beverage made… on pouring into it a tea-spoonful of spirit of hartshorn. This person being in the habit of frequently partaking of tea in other houses where she went to work, and being constantly in the habit of adding a tea-spoonful of hartshorn, without having observed that singular appearance which her own tea leaves produced.

She made a complaint to the grocer from whose shop the tea was purchased. This person… having paid a fair price for his commodity, took a sample of the suspected tea leaves to Mr. Accum the chemist, who analyzed it, and pronounced it to contain toxic copper. So unexpected a result induced the vendor… whose whole support depended on the rectitude of a fair tradesman, to inquire into the fraud committed upon him.

He consulted some of his friends who received their tea from the same quarter, and it became evident that the deceptions practiced in this diabolical branch of commerce were greater than was by him expected.”

Accum’s anger at this audacity and unscrupulousness awakened his desire to warn the general public about the extent of such adulteration. This rage, coupled with technical competence and his talent for expressing complex concepts in a way that was easily understood flowed into his most well-known work: “A Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons”.

Published in January 1820, this book was the first to address the topic of food adulteration and was a hit. The first edition was sold out within a month. The presses ran full-tilt, and the book became the most comprehensively reviewed chemistry textbook of all time [6,7]. Accum was at the highpoint of his career (see Fig. 3).

References

[1] João Paulo André, Fredrick Accum: An important nineteenth-century chemist fallen into oblivion, Bull. Hist. Chem. 2018, 43, 79.

[2] Frederick Kurzer, A History of the Surrey Institution, Ann. Sci. 2000, 57, 109-141. https://doi.org/10.1080/000337900296218

[3] Fredrick Accum, Wikipedia (accessed August 2024)

[4] James Millar, XXXVII. On poisonous tea-leaves, Phil. Mag. 1819, 54, 28, 218-219. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786441908652215

[5] James Miller, Gaz. Health 1819, 4, 372.

[6] C. A. Browne, Recently Acquired Information concerning Fredrick Accum, 1769-1838, Chymia 1948, 1, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.2307/27757110

[7] Accum added some reviews to his 1821 book “Culinary Chemistry.” See: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/60163/60163-h/60163-h.htm

The article has been published in German as:

- Aufstieg und Fall des Fredrick Accum: Da ist der Tod im Topf,

Klaus Roth,

Chem. unserer Zeit 2024, 58(3), 156-168.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ciuz.202300034

and was translated by Caroll Pohl-Ferry.

Death in a Pot: From England’s Famous Chemist to Exiled and Forgotten – Part 2

Let’s take a closer look at the book published by Fredrick Accum in 1820 about simple methods for detecting food adulteration

Death in a Pot: From England’s Famous Chemist to Exiled and Forgotten – Part 3

From the tragic case of Fredrick Accum, the significance of his work to this day, and the current state of food adulteration

See similar articles by Klaus Roth published on ChemistryViews.org