Die Sendung mit der Maus (The Show with the Mouse) is a popular German children’s television program. It uses a mix of animated segments, live-action features, and short educational documentaries to explain complex topics in a simple, engaging way. Each episode typically includes the famous “Maus-Spots” (Mouse spots), which are short, funny cartoons featuring the Mouse character. The program has gained iconic status in Germany due to its unique ability to make learning fun and accessible for children and at the same time explain topics in ways that also appeal to adults.

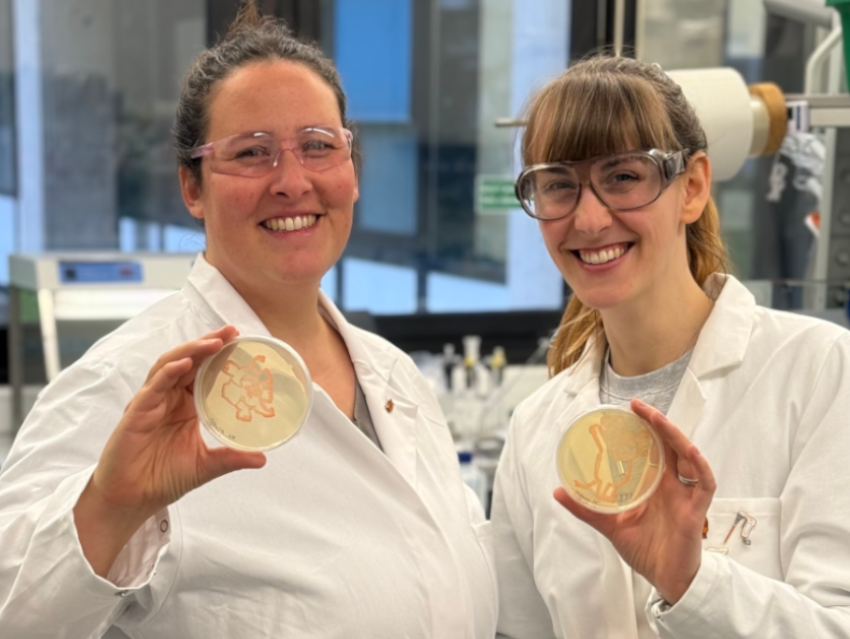

In a recent show, Lena Daumann, a Professor at Heinrich-Heine University in Düsseldorf and her Ph.D. student Sophie Gutenthaler-Tietze introduced their research on bacteria that use lanthanides in their metabolism [1]. Here, they talk with Vera Koester for ChemistryViews about their research and experiences filming for the popular German children’s program as well as with other outreach activities.

Rare earths are not exactly the kind of research topic you would usually explain to children. How did you get onto the famous “Sendung mit der Maus”?

Lena Daumann: It all started with the so-called “Türen auf mit der Maus-Tag” (Open Doors with the Mouse Day). On October 3rd, across Germany, labs, institutes, companies, castles, police stations, and so forth open their doors to show kids between the ages of six and twelve what they do. This year, over 750 “doors” opened across Germany for the public.

The event is managed through the website of the “Sendung mit der Maus”, where you can submit a proposal with what you want to show. I applied with an experimental lecture on rare earth elements, followed by tours of our labs where we give insights into how we want to tackle the problem of rare earth recycling. And not only did my “door” get accepted, but the organizing team also selected us, out of all entries, to be featured in a “Sachgeschichte” (educational story) for the TV show.

The event is managed through the website of the “Sendung mit der Maus”, where you can submit a proposal with what you want to show. I applied with an experimental lecture on rare earth elements, followed by tours of our labs where we give insights into how we want to tackle the problem of rare earth recycling. And not only did my “door” get accepted, but the organizing team also selected us, out of all entries, to be featured in a “Sachgeschichte” (educational story) for the TV show.

It already sounds like you have some experience with science outreach.

Lena Daumann: Yes, I have been doing science outreach since gradschool, it’s something that I really enjoy doing. And luckily I now have a team that feels the same.

In Munich, I had a two-year citizen science project with a local school where every Friday the school students would come to our labs and do research on green methods for recycling of rare earth elements. Sophie has also been in front of TV cameras before. So, when we are approached to share our research with the public, we are always happy to do it.

How did it then proceed? I assume the film crew didn’t just show up one day, right?

Lena Daumann: No [laughed]

First, the director called me for an interview, and I explained to her what my research is about and what we could show. I also involved Sophie at this stage because we already have done a lot of outreach in the context of rare earth elements and bacteria together.

Together, we then went through all the equipment we have, explained our scientific workflow, and tried to break down how we could explain to kids what we’re doing.

Sophie Gutenthaler-Tietze: Yes exactly, it is quite a challenge to figure out how much you will be able to show, as you only have seven minutes for a “Sachgeschichte” and it needs to be a full story in order to be suitable for children.

Even though Lena and I love to think in pictures anyway, doing a format for kids starting from three years old is on another level. For example, when you talk about metals, you have to explain what a metal is in the first place. You always need to make sure to build a connection between concepts, subjects, and objects kids already know. You really have to think about all those little details, because when you do science outreach for adults you don’t have to start with the word metal, right?

That’s right.

Lena Daumann: And we also have to say the director, Nina Lindlahr, was helping us a lot by constantly reminding us, “No, that’s too complex. We need to break it down into smaller steps.”

Then Nina wrote the first screenplay, and we edited it on paper, met again, and as soon as we had found a good storyline, two days of shooting followed.

Sophie Gutenthaler-Tietze: What I really want to emphasize is that quite a bit of preparation goes into two days of shooting. You have to make sure that everything is prepared for the experiments you want to do, so in our case that the bacteria are in the right growth phase and so on. We really tackled this as a team and a lot of the other group members were involved behind the camera to help with the preparations in the lab. It is not only the people in front of the camera but also the people behind the scenes that make science communication possible.

That must have been quite a disruption of the normal lab work. Was everybody happy with stopping their normal work?

Sophie Gutenthaler-Tietze: The whole team was excited about “Sendung mit der Maus” coming to our lab. I think for a lot of scientists in Germany it is a childhood dream to be involved with the “Sendung mit der Maus”. So many of us got excited about science (or how things work) in the first place because of that show!

With the camera team spending two days in your lab, they recorded much more than they in the end used for the show?

Sophie Gutenthaler-Tietze: Yes, that’s the sad bit about filming, that you have these really fun moments in front of the camera with cool ideas, but in the end, you only have seven minutes. I would have had a hard time picking what to show in the final episode, so I definitely would not want to change jobs with a director.

Did you receive any feedback from children, maybe from family or friends who watched the show?

Sophie Gutenthaler-Tietze: Yes, my nieces and nephews are big “Maus”-fans and got really excited about seeing me on TV. I would say it’s kids-approved.

Lena Daumann: Oh yeah! I watched it with my son, and he was really excited about recognizing the university, as he often accompanies me in my office.

And people I studied chemistry with a long time ago, sent me photos of their kids sitting in front of the TV enjoying the episode. We did get a lot of positive feedback. I think it might have been our outreach activity with the biggest impact so far.

With all of your outreach experience, why would you say is it important that kids get involved in chemistry even at this young age?

Lena Daumann: I feel that kids at a very young age are already really good experimentalists and incredibly curious, and that needs to be nurtured. For example, I do lots of science experiments with my son at home. But not everyone has parents that know how to do that or have any “equipment”.

For the Open Door Day with the Maus, we also prepared 150 experimentation kits for kids of all ages to do at home with instructions for fun experiments using normal household items and food. Our kits had some pipettes and other lab stuff they could use to explore for example red cabbage indicator with all its beautiful colors and the concept of pH. We could give out these kits because we got funding from the HHU Citizens‘ University office.

Even toddlers are already little scientists, they investigate things all the time. Like they drop an egg and realize “Oh just now it was a hard thing and now it’s slimy.” They observe and maybe drop an egg again.

Sophie Gutenthaler-Tietze: Kids are just so curious. I think it’s important to foster that interest so that they don’t lose it. We definitely need the next generation of scientists. Experiments-kits like the one Lena talked about are one possibility to get them in touch with experiments and science, another option is public events like Soapbox Science or science museums—they also have great offers for kids!

Obviously, as a Ph.D. student, you have lots of other tasks to do, so one could think why are you doing this and not just focusing on your research?

Sophie Gutenthaler-Tietze: First, I’m very lucky to have Lena as a supervisor, who is also super engaged in science outreach and always supports the outreach activities I want to do. And I would say, when you’re motivated about something and love what you are doing, or at least for me that’s the case, I want to share it and I always want to tell people how cool and amazing it is. Every outreach activity I do is a motivation boost for my own research, especially when you see that you can spread the joy that you have for science.

And I also believe science outreach is very important for our society and in terms of representation. We need to show the full diversity of scientists to inspire the next generations. In my opinion, it is worthwhile taking time for this during a Ph.D.

On “Die Sendung mit der Maus”, you look very professional on TV and come across as really cool. So, some people might think, “I could never do that”. Many chemists already struggle to make their work understandable and interesting for non-scientist adults. What are some good ways to learn this skill?

Sophie Gutenthaler-Tietze: Thank you, that is nice to hear! I definitely was nervous, but the film team was very relaxed and the moderator Jana Forkel created a great atmosphere and made it really easy for me! And luckily it was not my first time in front of a camera, that helped a lot.

So my tip would be: “Practice!” I think almost every person that does a Ph.D. or senior people in science tend to like to push themselves a bit further, right? In that sense, I would also see science communication as something that can be your challenge to push yourself a bit. The first time you’re a bit uncomfortable before the camera, but the next time you already have fun in front of it.

Lena Daumann: And of course, there are also lots of different formats of science outreach. So not everyone is maybe comfortable with TV and doesn’t have to be. Other options include standing behind a table display at a university science night, doing a lab tour on an open day, or visiting schools for hands-on experiments.

Sophie Gutenthaler-Tietze: You can also write an article for example. And as I said, practice really helps. Talk to the non-scientists in your family or among your friends and ask them for feedback. For me, that always helps.

I think that’s a great tip. So, what motivated you to become a scientist?

Lena Daumann: I have always been very fond of experimenting. Already when I was a small kid, I was all about extracting, mixing, observing. I also bred frogs and butterflies, whatever. I was very into the natural sciences and actually wanted to become a professor since I was in kindergarten. I didn’t really know what a professor was at that time, and in my imagination, it was more or less an old white-haired guy in a lab coat who could do experiments all day. And I thought “Oh that’s cool I wanna do that!”.

Sophie Gutenthaler-Tietze: I would say that for me the chemistry thing started a bit later. When I first had chemistry in school, I was super amazed and saw, “Okay, that’s something I’m really interested in and I really love it.” Before that, I always wanted to become a vet and work with animals. But after my first chemistry lecture, I was sure, chemistry is what I want to do. And I went the way step by step, never having the foresight that I would actually do a Ph.D someday. But I’m so glad that I got here.

You just mentioned this white-haired old man in a white coat chemist. How important are role models?

Lena Daumann: I think representation matters. When I started studying chemistry over 20 years ago, there weren’t (m)any female professors in my direct vicinity.

Sophie Gutenthaler-Tietze: Yes, representation definitely matters. During my studies, I had Lena as a Professor and it really made a difference to see a female scientist talking about chemistry with so much passion, energy, and excitement.

Sophie Gutenthaler-Tietze: Yes, representation definitely matters. During my studies, I had Lena as a Professor and it really made a difference to see a female scientist talking about chemistry with so much passion, energy, and excitement.

Lena Daumann: Also when talking about representation: I would also like to mention the importance of realistic science representation. That includes wearing lab coats and safety goggles when you are in front of a camera in the lab. In my lab at HHU, we do not sacrifice safety for the sake of a better photo. Also, on the TV show we did show a lot of experiments, and it was important to me that people of the team that do the actual experiments on a day-to-day basis would be shown doing them. If a professor that rarely does their own experiments anymore, then suddenly stands in front of the camera when the TV teams shows up, it’s just not authentic.

We have heard that your research involves rare earth elements and bacteria. Could you tell us more about your work?

Lena Daumann: Sure! I’m a bioinorganic chemist, which means I want to understand the roles different metal ions play in living processes. And I am specifically interested in rare earth elements. Other than their name suggests, they are not particularly rare and are found everywhere in nature, and also in our daily lives. We need them in cell phones, computers, in the strongest magnets, in the green energy sector, and in medicine. And it turns out: bacteria use these elements as well!

They use lanthanides, such as lanthanum or neodymium, as Lewis acids in the active sites of key enzymes for their metabolism. It was long thought improbable that living organisms use these elements, because they are poorly bioavailable and the somewhat unfortunate common misconception that lanthanides, as part of the rare earth elements, are rare.

And how long has it been known that bacteria use rare earth elements?

Lena Daumann: In 2011, there was the first paper on this by Japanese scientists [2]. They found that adding lanthanum to the growth medium of a methylotrophic bacterial strain induced the expression of a methanol dehydrogenase-like protein. But for a couple of years this study was overlooked, maybe also because the strain was just fine without lanthanides, so in this case these elements were not essential.

In 2014, a study by microbiologists from Nijmegen, the Netherlands, however, reported a strain that was dependent on lanthanides for growth [3]. And that really got the ball rolling in this field. So, we now distinguish between bacteria that can use lanthanides (and they will, if they are around!) and bacteria that need lanthanides as essential elements for their C1-metabolism.

So how do these bacteria now help with rare earth element recycling?

Lena Daumann: While most of the work we do is trying to learn more about how bacteria sense, take-up, use, and store these elements, we and others also aim to make specific modifications to proteins, enzymes, and other biomolecules involved in this process. We want to leverage the know-how of nature to separate and recover rare earth elements.

Sophie, do you maybe want to talk about your Ph.D. project?

Sophie Gutenthaler-Tietze: Yeah, for sure. In my Ph.D. I focus on two different projects, both with the greater goal of laying the groundwork for bio-inspired and sustainable REE-recycling [rare earth element]. One project is all about bio-inspired peptides which we modify in order to increase their Ln-affinity. And the other one is about figuring out how these bacteria acquire lanthanides in the first place. For this, specific chelators, termed lanthanophores, were suggested by us and other scientists in the field.

What’s really exciting is that we recently identified a small metallophore [5] which is actually involved in the Ln-metabolism. But as often in science, it turns out it is not as easy as initially anticipated [6]. So there is still so much to discover and understand—it never gets boring!

Do you also work with other metals than lanthanides?

Lena Daumann: We have recently shown that not only can we use lanthanides for these bacteria, but also some radioactive actinides, if they have the right ionic radius and a 3+ charge. We demonstrated that our bacteria and their Ln-dependent enzymes can actually use americium and curium instead of lanthanides [4]. So, also actinides can have a biological role, although that might not be the one that they have in nature. This could be, of course, interesting for the separation of not only lanthanides among each other, but also from the actinides.

Very fascinating research. Thank you very much for the interview.

References

[1] Seltene Erde in “Die Maus”, Das Erste, WDR, Germany, 22.09.2024. (for our readers from Germany)

[2] Y. Hibi, K. Asai, H. Arafuka, M. Hamajima, T. Iwama, K. Kawai, Molecular structure of La3+-induced methanol dehydrogenase-like protein in Methylobacterium radiotolerans, Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2011, 111(5), 547–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2010.12.017

[3] Arjan Pol, Thomas R. M. Barends, Andreas Dietl, Ahmad F. Khadem, Jelle Eygensteyn, Mike S. M. Jetten, Huub J. M. Op den Camp, Rare earth metals are essential for methanotrophic life in volcanic mudpots, Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 16(1), 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.12249

[4] Helena Singer, Robin Steudtner, Andreas S. Klein, Carolin Rulofs, Cathleen Zeymer, Björn Drobot, Arjan Pol, N. Cecilia Martinez-Gomez, Huub J. M. Op den Camp, Lena J. Daumann, Minor Actinides Can Replace Essential Lanthanides in Bacterial Life, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202303669

[5] Alexa M. Zytnick, Sophie M. Gutenthaler-Tietze, Allegra T. Aron, Zachary L. Reitz, Manh Tri Phi, Nathan M. Good, Daniel Petras, Lena J. Daumann, Norma Cecilia Martinez-Gomez, Identification and characterization of a small-molecule metallophore involved in lanthanide metabolism, PNAS 2024. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2322096121

[6] S. M. Gutenthaler-Tietze, M. Mertens, M. T. Phi, P. Weis, B. Drobot, A. Köhrer, R. Steudtner, U. Karst, N. C. Martinez-Gomez, L. J. Daumann, Comparative Binding Studies of the Chelators Methylolanthanin and Rhodopetrobactin B to Lanthanides and Ferric Iron, ChemRxiv 2024. https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2024-9f26t

Lena J. Daumann, born 1983 in Emmendingen, Germany, studied chemistry at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, and received her Ph.D. in bioinorganic chemistry from the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, in 2013. After postdoctoral positions at Berkeley, USA, and Heidelberg, she accepted a professorship in Bioinorganic and Coordination Chemistry at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität (LMU), Munich, Germany, in 2016. Since October 2023, she has been Professor of Bioinorganic Chemistry at Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf (HHU), Germany.

Lena’s research focuses on the role of lanthanide elements in bacteria. In addition, she develops sustainable, bio-inspired separation and recycling methods for this group of elements. She is involved in several collaborative research projects funded by the German Research Foundation.

Lena’s research focuses on the role of lanthanide elements in bacteria. In addition, she develops sustainable, bio-inspired separation and recycling methods for this group of elements. She is involved in several collaborative research projects funded by the German Research Foundation.

Among other awards, Lena has received the Ars Legendi Prize for Chemistry and the Bavarian Prize for Excellence in Teaching. In 2020, she received a Starting Grant from the European Research Council (ERC).

Sophie Gutenthaler-Tietze studied chemistry at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität (LMU) and started her Ph.D. there in Lena Daumann’s group in 2020 and moved with her to Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf (HHU) in 2024 to finish her PhD on bio-inspired Ln-binding peptides and bacterial metallophores.

During her studies, she was supported by the Deutschlandstipendium and throughout her Ph.D. by a scholarship from the Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes. She is a Lindau Alumna of 2022 and has won several awards for her Bachelor’s and Master’s theses, as well as prizes for presenting her Ph.D. projects at conferences.

Sophie Gutenthaler-Tietze is a science communication enthusiast and was a 2022 Soapbox Science speaker in Munich. She then joined the Soapbox Science team and is now on the organizing side. In addition, she has appeared on TV shows like Princess of Science and has moderated episodes for the TV show Planet Schule.

Selected Publications

- S. M. Gutenthaler-Tietze, J. Kretzschmar, S. Tsushima, R. Steudtner, B. Drobot, L. J. Daumann, Reversing Lanmodulin’s Metal-binding Sequence in Short Peptides Surprisingly Increases the Lanthanide Affinity: Oops I Reversed it again!, ChemRxiv 2024. https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2024-wnd7x

- Chia-Lin Lin, Pei-Chi Huang, Simone Graessle, Christoph Grathwol, Pierre Tremouilhac, Sylvia Vanderheiden, Patrick Hodapp, Sonja Herres-Pawlis, Alexander Hoffmann, Fabian Fink, Georg Manolikakes, Till Opatz, Andreas Link, M. Manuel B. Marques, Lena J. Daumann, Manuel Tsotsalas, Frank Biedermann, Hatice Mutlu, Eric Täuscher, Felix Bach, Tim Drees, Steffen Neumann, Nicole Jung, Stefan Bräse, Supporting Sustainability of Chemistry by Linking Research Data with Physically Preserved Research Materials, ChemRxiv 2023. https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2023-2dd4c

- Helena Singer, Robin Steudtner, Ignacio Sottorff, Björn Drobot, Arjan Pol, Huub J. M. Op den Camp and Lena J. Daumann, Learning from Nature: Recovery of rare earth elements by the extremophilic bacterium Methylacidiphilum fumariolicum, Chem Comm. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3CC01341C

- H. Singer, R. Steudtner, A. S. Klein, C. Rulofs, C. Zeymer, B. Drobot, A. Pol, N. C. Martinez-Gomez, H. J. M. Op den Camp, L. J. Daumann, Minor Actinides Can Replace Essential Lanthanides in Bacterial Life, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202303669

- S. M. Gutenthaler, S. Tsushima, R. Steudtner, M. Gailer, A. Hoffmann-Röder, B. Drobot, L. J. Daumann, Lanmodulin peptides–unravelling the binding of the EF-Hand loop sequences stripped from the structural corset, Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers 2022, 9(16), 4009–4021. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2QI00933A

- H. Singer, B. Drobot, C. Zeymer, R. Steudtner L. J. Daumann, Americium preferred: lanmodulin, a natural lanthanide-binding protein favors an actinide over lanthanides, Chemical Science 2021, 12(47), 15581–15587. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1SC04827A

- Lena J. Daumann, Essential and Ubiquitous: The Emergence of Lanthanide Metallobiochemistry, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201904090

- Bérénice Jahn, Arjan Pol, Henning Lumpe, Thomas R. M. Barends, Andreas Dietl, Carmen Hogendoorn, Huub J. M. Op den Camp, Lena J. Daumann, Similar but Not the Same: First Kinetic and Structural Analyses of a Methanol Dehydrogenase Containing a Europium Ion in the Active Site, ChemBioChem 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.201800130

- Lena J. Daumann, David S. Tatum, Benjamin E. R. Snyder, Chengbao Ni, Ga-lai Law, Edward I. Solomon, Kenneth N. Raymond, New Insights into Structure and Luminescence of EuIII and SmIII Complexes of the 3,4,3-LI(1,2-HOPO) Ligand, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137(8), 2816–2819. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja5116524

- Lena J. Daumann, Gerhard Schenk, David L. Ollis, Lawrence R. Gahan, Spectroscopic and mechanistic studies of dinuclear metallohydrolases and their biomimetic complexes, Dalton Transaction 2014. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3DT52287C

- Lena J. Daumann, Peter Comba, James A. Larrabe, Gerhard Schenk, Robert Stranger, German Cavigliasso, Lawrence R. Gahan, Synthesis, Magnetic Properties, and Phosphoesterase Activity of Dinuclear Cobalt(II) Complexes, Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52(4), 2029–2043. https://doi.org/10.1021/ic302418x