Absinthe is in! After decades of a nearly complete ban, this high-proof beverage has been back on the EU market since 1991. This favorite drink of Bohemian Parisians at the end of the 19th century hints at a touch of decadence that has a decided promotional effect today. After a couple of glasses, those with a creative nature were supposedly kissed by the same Green Fairy that had previously intoxicated and inspired Baudelaire, Verlaine, Wilde, Toulouse-Lautrec, and van Gogh to create masterpieces.

We hope to uncover what chemical trick the “fée verte” used back in the day, and to determine whether we can still hope for a kiss from the Green Fairy when consuming modern absinthe.

1 A Brief History of Absinthe

1.1 Discovery of Distillation and of Absinthe

After the discovery of distillation by Arabs in the 8th century, it became possible to produce alcoholic herbal extracts. Monks in the Middle Ages used these to prepare herbal liqueurs by adding sugar. The Bénédictine and Chartreuse produced by Benedictine and Carthusian monks are still consumed today.

Absinthe is a high-proof alcoholic beverage whose flavor stems from the wormwood shrub Artemisia absinthium (see Fig 1), which is native to central and southern Europe.

|

| Figure 1. Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium). |

Wormwood is in the Asteraceae family, within a species-rich genus that also includes tarragon, mugwort, and sagebrush. Growing to over a meter in height, this bush is native to southern Europe, North Africa, and Asia. It has silver-gray leaves with felt-like hairs and small, spherical, yellow flowers. For absinthe production, the parts of the plant above ground are usually harvested upon flowering.

Absinthe was originally produced around 1800 in French-speaking Switzerland. Both Dr. Pierre Ordinaire [1] and his landlady, the herbalist known as Mother Henriod (Suzanne-Marguirite Motta) are named as its inventors. Both lived in Couvet, near Neuchâtel, in French-speaking Switzerland.

It has been conclusively documented that a recipe for absinthe was sold to Major Dubied by Mother Henriod in 1797. Dubied began commercial production the following year [2,3]. Sales increased rapidly, and by 1805, his son-in-law Henri-Louis Pernod (1776–1851) founded a branch factory known as Pernod Fils in Pontarlier, in nearby France.

Because the wormwood plant was an old remedy for worms and malaria, absinthe also had a reputation for being effective against these diseases. Beginning in 1830, this was exploited by French military leadership: All 100,000 of the soldiers serving in North Africa were given a daily ration of absinthe. The assumption that wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) is effective against malaria likely stems from confusion with Artemisia annua, which has been proven to be effective against malaria.

In any case, business flourished, especially because soldiers returning from Algeria continued to demand their daily absinthe when they came home. It became well-known, but not popular. This changed abruptly: In 1873, barely 7,000 hectoliters of absinthe were consumed in France, by 1900, this had risen to an astronomical 240,000 hectoliters [4]. These volumes refer to the pure ethanol.

Additional Info:

|

1.2 What Drove the French to Absinthe?

Until the fall of Napoleon III in 1870, the opening of premises that could sell alcoholic beverages (debits de boissons) was strictly limited. This had political motivations, because state powers were suspicious of gathering places where heavy drinking and politicizing occurred. After Napoleon’s fall, all bureaucratic obstacles were dropped and with a spirit of optimism, bars, cafés, and cabarets sprouted like mushrooms. In Paris, there was eventually more than one bar per 100 inhabitants, more than any other city in the world. For many people, bars were places where they could escape their wretched lives in their poorly heated and cramped apartments for a few hours. Living conditions and hygiene were generally catastrophic, with cholera still raging in Paris in 1860.

In a bar, people could read the newspaper, make use of available writing utensils, or get invited to a game at the billiard tables. Women, for whom a trip to the bar was previously thought to be unseemly, socialized there, and the public consumption of alcohol became socially acceptable for everyone, from the workers to the bohemians to the bourgeoisie.

Originally, the Romani people who immigrated to France from Bohemia were called Bohemians and earned their living as musicians and jugglers. Later, this term expanded in the vernacular to include unkempt, seemingly care-free people who lived a footloose life. A “Vie de Bohème” was a life with dissolute ways and loose morals—wonderful material for novels and operas, such as La Bohème by Giacomo Puccini.

The exploding consumption of absinthe had a second cause as well: Absinthe is based on brandy, which was distilled from inferior wine. After 1850, methods of production were developed for producing spirits from fermented turnips or grain. This turnip brandy initially had only a limited market because wine was plentiful and cheap. However, things changed drastically in 1860, when the grapevine louse Phylloxera vitifoliae was introduced to France from America. By 1920, this pest had destroyed nearly all French grapevines and drove two generations of vintners to ruin.

The grapevine louse reached Klosterneuburg near Vienna in Austria in 1867. In 1874, it reached the Annaberg Garden near Bonn, in 1907, the Moselle, and in 1931, it got to Baden in Germany. Many scientific studies investigated the complicated reproductive cycle of the grapevine louse, which primarily attacks the roots in winter. After many years, a solution was found: Native vines of Vitis vinifera were grafted onto American rootstock of the species Vitis riparia and Vitis berlandieri, which are resistant to the louse.

The severe crop failures caused wine to become expensive. This also affected absinthe producers, who quickly switched to using the cheaper spirits based on turnips and grain. Based on the relative amounts of ethanol, absinthe was now suddenly cheaper than wine! It was the interplay of all these factors—the spirit of optimism after the fall of Napoleon III, the more permissive lifestyle of the French and the partial emancipation of women that accompanied it, the development of rational production methods for cheap industrial alcohol, and the high price of wine resulting from the grapevine louse—that explains the collective absinthe frenzy of the French in the Belle Epoque.

1.3 The Sharp Decline

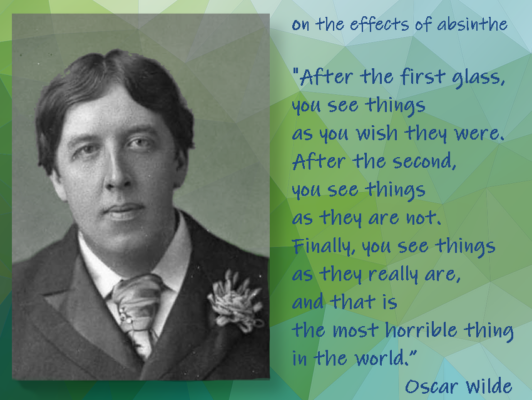

Between 1870 and 1914, the French drank two thirds of the absinthe produced in the world. Absinthe was cheap, bars and cabarets teemed with life, and the daily afternoon drink of absinthe in the “green hour” (heure verte) became a ritual for many French people. Bohemians, poets from Baudelaire to Verlaine, painters from Toulouse-Lautrec to van Gogh, many actors, and professors raved about the fantastic effects of absinthe. Oscar Wilde coined the term “the green fairy”, who embraces the drinker after a few glasses and helps him attain amazing bursts of creativity. The notion that absinthe was an aphrodisiac was a powerful driver of sales. In short, absinthe was “in”.

The elevated consumption of absinthe, as well as the overall increase in alcohol consumption of the French, had consequences: The number of inmates in institutions for the mentally ill and suicidal increased. Chronic absinthe abuse led to addiction, mental confusion, a decrease in mental faculties, dementia, and severe hallucinations, followed by depression, cramps, paralysis, and finally death. This syndrome became known as absinthism. Calls for a ban from medical practitioners grew as absinthe was not only held responsible for psychological disorders, but suddenly also for tuberculosis, syphilis, criminality, and overall moral decline.

Ironically, the military, which had first made absinthe popular in France, now became a relentless opponent. The Ministry of War raised the alarm, demanding a ban because of the poor physical condition of Frenchmen called to military service. French wine producers joined in, naturally interested in lower absinthe consumption and higher (expensive) consumption of wine. Many physicians and eventually the Académie de Médicine supported a ban.

Nevertheless, the French continued to drink their absinthe, undaunted. It took a spectacular family drama to bring about a sudden mood swing in Europe: On August 28, 1905, Jean Lanfray, a 31-year-old vineyard laborer in the Swiss canton of Vaud, started his day at around 6:00 with two glasses of absinthe before going to a café, where he drank a crème de menthe and a cognac.

While at work in the vineyard, he drank seven glasses of wine. At four in the afternoon, he drank a coffee with brandy at the café before proceeding to drink another liter of red wine at home. There he got into a violent argument with his wife about the fact that she had not cleaned his boots. The argument escalated and he shot his wife. He then shot his four-year-old daughter Rose as she entered the room and his two-year-old daughter Blanche, who was sleeping in the next room. He then tried to kill himself. Jean Lanfray was charged with four counts of murder because his wife was pregnant.

Despite the comparatively small amount of absinthe he consumed early in the morning, the court-appointed expert, the famous psychiatrist Albert Mahaim, ascribed the cause of the murders unambiguously and exclusively to absinthism. The accused was sentenced to 30 years in prison. He hanged himself in his cell a few days after his conviction.

This trial made massive waves that resulted in bans in nearly every country: Belgium in 1905, Switzerland by referendum in 1908, the USA in 1912, and France in 1915. Friedrich Ebert, president of the German Reich, signed a law on April 27, 1923, forbidding the production and importation of absinthe in Germany.

Absinthe abruptly disappeared from the market. The traditional producers in France and Switzerland, led by Pernod, switched their production over to anise brandies without wormwood additives. Known as pastis, these are still very popular today.

The ban on absinthe was lifted in 1981 in Germany, though the use of wormwood oil was initially still banned under flavor regulations. Absinthe has been allowed in Germany and other European countries since 1991, according to EU law. In Switzerland, motherland of absinthe, the ban was lifted in June of 2004. Since then, the 10,000 L that had been illegally produced annually can be sold over the counter again. Over 100 different varieties of absinthe, primarily produced in Spain, France, and the Czech Republic, are currently available on the German market.

2 In Search of the Green Fairy

2.1 The Green Fairy

The green fairy was the euphoric and stimulating effect of absinthe. If the reports of artists of the time are to be believed, many of their masterworks were created while in this intoxicated state. Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) described the effect: “After the first glass, you see things as you wish they were. After the second, you see things as they are not. Finally, you see things as they really are, and that is the most horrible thing in the world.”

If one drank too much, the green fairy turned into a monster that gave the drinker a severe hangover. Chronic abuse led to mental disorders and severe muscle cramps; in advanced stages, it eventually led to personality breakdown, suicidality, memory disorders, paralysis, and death.

Although the observed symptoms correspond to those of chronic alcoholism, the majority of the scientific community at the end of the 19th century were convinced that, in contrast to other alcoholic beverages, absinthe was a danger to health. They firmly believed in a new disease: absinthism. This belief inspired scientific studies meant to prove the harmfulness of wormwood as opposed to the harmlessness of ethanol. It was believed that the green fairy was to be found somewhere in the wormwood.

In the experimental hunt for the fairy, they used pure ethereal oil (wormwood or absinthe oil) that was obtained directly from the plants by steam distillation. This oil roughly corresponds to the volatile components obtained in the production of absinthe by distillation.

2.2 Production of a Small Absinthe Supply

Top-quality absinthe can only be produced from premium spirits and herbs of the highest quality. Below is an original recipe from Pontarlier in 1855 [5,6]. There are countless variations on the ingredients and procedures given in this basic recipe. The botanical ingredients also include licorice root, nutmeg, elder, lemon balm, juniper, speedwell, and many others.

1st Step: Maceration and Distillation

A total of 95 L of plant-derived brandy (85 vol% ethanol) is poured over a mixture of 2.5 kg wormwood (Artemisia absinthum), 5 kg anise, and 5 kg fennel. After 12 h at room temperature, 45 L of water is added, and the mixture is slowly distilled until 95 L of distillate is obtained.

The first fraction has an alcohol content of 80–60 vol% and contains mainly the highly volatile, aromatic components of the wormwood flavor; the middle fraction contains mostly the clove- and cinnamon-like components [7,8].

2nd Step: Coloration

A mixture of 1 kg wormwood plants, 1 kg hyssop, and 500 g lemon balm is covered with 40 L of the distillate obtained in the first step.

After some time, the mixture is filtered and the resulting clear, pale-green solution is combined with the remaining 55 L of distillate from the first step and diluted to a total volume of 100 L with water. The ethanol content of the absinthe obtained by this method is 74 vol%.

A gas chromatogram of wormwood oil gives an idea of the number of volatile components in wormwood: It contains hundreds of substances. Because the basis of good absinthe consists of at least a half dozen different herbs that give off their volatile components during distillation and their non-volatile components in the maceration, absinthe is an extremely complex mixture of substances from a chemical point of view.

In the next section, the search for the green fairy includes self-experiments and a possible molecular formula, as well as the right way to drink absinthe.

References

[1] A.-M. Villon, L’absinthe: Histoire – Fabrication – Traitement, La Nature 1894, 22, 149, 181.

[2] M.-C. Delahaye, L’Absinthe, Histoire de la fée verte, Berger-Levrault, Straßburg, France, 1983. ISBN: 9782701305325

[3] M.-C. Delahaye, L’Absinthe – Son Histoire, Musée de l’Absinthe, Auvers-sur-Oise, France, 2001. ISBN: 9782951531628

[4] Michael Robert Marrus, Social Drinking in the Belle Epoque, J. Soc. Hist. 1974, 7(2), 115–141. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh/7.2.115

[5] Historical Recipes, feeverte.net. (archived version accessed March 1, 2024)

[6] W. N. Arnold, Absinthe, Sci. Am. 1989, 260, 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0689-112

[7] D. W. Lachenmeier et al., Absinthe, a Spirit Drink – Its History and Future from a Toxicological-Analytical and Food Regulatory Point of View, Dtsch. Lebensm.-Rundsch. 2004, 100, 117–129. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3459437

[8] D. Lachenmeier, Absinth: eine Spirituose mit Vergangenheit und Zukunft aus analytischer und lebensmittelrechtlicher Sicht, www.ua-bw.de, 2008. (accessed March 1, 2024)

The article has been published in German as:

- Der Zauber der Grünen Fee,

Klaus Roth,

Chem. unserer Zeit 2005, 39, 130–136.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ciuz.200590014

and was translated by Caroll Pohl-Ferry.

Absinthe – The Magic of the Green Fairy – Part 2

Self-experiments, a possible sum formula in search of the green fairy, and the right way to drink absinthe

Absinthe – The Magic of the Green Fairy – Part 3

How toxic is thujone and how much of it is ingested when drinking absinthe?

See similar articles by Klaus Roth published on ChemistryViews.org