Street, City, Country

Haus „Zum Sessel“, Totengässlein 3, Basel, Switzerland

Who Was There?

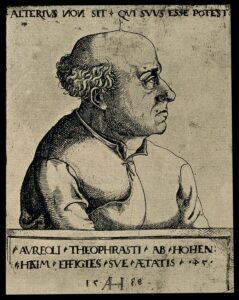

Paracelsus (Theophrastus Bombast von Hohenheim) (1493–1541)

Figure 1. Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim [Paracelsus]. Reproduction, 1927, of etching by A. Hirschvogel, 1538. © Wellcome Collection gallery (2018-03-23) CC BY 4.0

When Did He Live There?

1527–1529

What is it Today?

The Pharmacy Museum of the University of Basel. It is located in the historic center of Basel.

Founded in 1924, the museum preserves its original form as a “scientific cabinet” and presents the history of medicines and their preparation. It houses one of the largest collections of pharmaceutical artifacts, including historical pharmacy equipment, an alchemist’s laboratory, ceramics, mortars, first-aid kits, medicines, and related books. The museum aims to explain the scientific, art-historical, and ethnological aspects of the history of pharmacy. It represents a scientific collection from the 1920s that has been preserved and expanded until today.

Original Building?

Yes.

Brief History of the House

The building was first mentioned in 1316 as the “Unter Krämern” bathhouse. From 1480, it was home to the renowned printer and publisher Johannes Amerbach (c. 1440–1513), followed by Johannes Frobenius (often called Froben; c. 1460–1527) in 1507, one of the most famous printers of his time. Erasmus von Rotterdam (c. 1466–1536), a Dutch philosopher, theologian, and humanist, stayed and worked in the house from 1514 to 1516. The house also hosted known illustrators such as Hans Holbein the Younger (1497–1543) and his brother Ambrosius (c. 1494–1519), as well as Urs Graf (c. 1485–1528), known for his woodcuts and engravings.

In 1527 and 1529, the famous physician and alchemist Paracelsus worked and lived there as Froben’s family doctor.

In 1917, the first pharmaceutical institute at the University of Basel was founded at this location.

What Is Paracelsus Known For?

His Life

Paracelsus was a Swiss physician, alchemist, and philosopher, renowned for revolutionizing medicine in the 16th century.

He was born in Einsiedeln, which was part of the Holy Roman Empire and under Austrian rule. His father was a physician, and his mother was probably a native of the Einsiedeln region and a bondswoman of Einsiedeln Abbey. Bondswomen were often tied to estates, households, or institutions, and their work could be agricultural, domestic, or otherwise.

Figure 2. Monument to his birthplace on the Teufelsbrücke (Devil’s Bridge) near Einsiedeln.

Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus von Hohenheim later became known as Paracelsus. Some believe that Paracelsus deliberately chose his name to position himself as superior to the second-century Roman medical writer Celsus. However, this interpretation is not universally accepted and remains controversial.

Between 1517 and 1524, he traveled extensively across Europe, including to Tyrol, where he visited mines and metallurgical workshops to study metallurgy and alchemy. It is historically uncertain whether he obtained his doctorate in Ferrara, in modern-day Italy.

In 1527, he became the city physician in Basel. He had the right to give lectures (in German). He criticized the professors for never truly seeing the sick, which caused great unrest among them, and he also harshly criticized the pharmacists. Examples of his rhetorical attacks on pharmacists and university physicians include:

“If your physicians only knew that their prince Galen … is in hell, from where he has sent letters to me, they would make the sign of the cross with a fox’s tail on themselves. In the same way, your Avicenna sits in the vestibule of the infernal portal.”

Galen (c. 129–c. 200 CE) was a Greek physician who made significant contributions to anatomy, physiology, and pharmacology. His ideas formed the basis of medical knowledge in Europe and the Islamic world well into the Renaissance.

Avicenna (Ibn Sina) (c. 980–1037 CE) was a Persian polymath and physician whose works in medicine were highly influential in the Islamic world and in Europe. His approach to medicine integrated Greek medical theories, especially those of Galen, with his own philosophical and scientific insights.

“Come then and listen, you impostors who prevail only by the authority of your high positions! After my death, my disciples will burst forth and drag you out into the light, and they will expose your filthy drugs with which, until now, you have surrounded the death of princes… Woe to your necks on the Day of Judgment! I know that the monarchy shall be mine. Mine also shall be the honor and the glory. Not that I praise myself: Nature praises me.”

Two years later, Paracelsus was forced to resign in disgrace after his abusive and bombastic behavior offended public opinion. He left Basel and continued to travel restlessly around Europe. He died in Salzburg in 1541.

His Doctrines

Paracelsus challenged the traditional medical practices of his time. He was revolutionary in proposing the use of one’s own observations of nature, rather than relying on ancient texts. He proposed that the world is made up of three elements or principles: salt, sulfur, and mercury.

He developed theories and medicines based on alchemy (chemicals and minerals) and is considered the father of toxicology, not least because of the famous quote ‘Dosis facit venenum’ (The dose makes the poison).

Alchemy is the ancient practice of transforming substances to bring to completion something that has not yet been completed. This can include a wide range of activities in nature, such as cooking, chemical transformations, and physiological processes like digestion. Alchemy sought to refine and transmute matter, believing that everything in nature could be perfected or transformed through certain mystical or chemical processes.

Chemistry, on the other hand, emerged as the scientific discipline that provides the key to unlocking the mystery of the universe created by a chemist and governed by chemical laws. It relies on empirical observation and experimentation to explain how matter behaves and transforms.

Paracelsus refuted ancient medical teachings and rejected the reliance on traditional herbal or organic remedies. Instead, he advocated for the use of mineral medicines, which were inorganic substances, in treating diseases. He believed that diseases were specific and could be targeted with specific remedies, or arcana, to cure them. The arcana would destroy and eliminate the poisons produced by a disease, which itself was due to the decay of the excreta produced by any chemical process. For instance, the emerging pandemic of syphilis in Europe at the time illustrated that diseases had identifiable causes and could be treated with precise chemical solutions, rather than general herbal cures.

Paracelsus also introduced a new branch of medicine called iatrochemistry, which integrated chemistry into medical practice. This field applied chemical principles to understanding and treating illnesses. However, the Paracelsians, a group of followers, believed that chemical knowledge was a mystical and almost secretive discipline, to be shared only among those inspired in the manner of a magus, a wise or magical figure. The iatrochemical doctrines became widely popular in the 17th century.

References/Sources

[1] Swiss Chemical Landmark 2020: Pharmaziemuseum der Universität Basel – Arbeitsort von Paracelsus, SCNAT Plattform Chemie, Haus der Akademien, Bern, Switzerland. (accessed November 24, 2024)

[2] Rudolf Wolf, Theophrastus Paracelsus von Einsiedeln in: Biographien zur Kulturgeschichte der Schweiz, Zürich 1861, S. 1–50.

→ Back to Overview: Guess the Houses and Molecules