In his 1820 book “A Treatise on Adulteration of Food and Culinary Poisons”, Fredrick Accum (1769–1838) described how every citizen could reliably detect the worst of the common types of food adulteration by simple means. Fredrick Accum should have had a place of honor in history as a pioneer of consumer protection. But that is not how things played out.

As previously mentioned, Accum’s book is a huge hit. The first edition is sold out within a month. The second edition appears three months after the first and sells out within a week. The reasons for which Fredrick Accum did not become a pioneer in consumer protection with this 1820 book about simple methods for detecting food adulteration are the subject of this final part of the article.

4 The Fall of Fredrick Accum

By exposing convicted perpetrators, Accum causes them economic difficulties and interferes with economic activity in London. This certainly doesn’t make him any friends and he must have expected retribution.

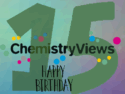

In the foreword of the second edition of his A Treatise on Adulterations of Food (see Fig. 8), which is released three months after the first edition and sells out within a week, he responds sharply to anonymous threats he hasreceived:

Figure 8. The “Death in the Pot” image on the title page of the second edition was made even more gruesome than that of the first edition (see Fig. 4). (Image: wikimedia commons, wellcome images L0001006, public domain)

“To those who have chosen anonymously to transmit to me their opinion concerning this book, together with their maledictions, I have little to say; but they may rest assured, that their menaces will in no way prevent me from endeavouring to put the unwary on their guard against the frauds of dishonest men, wherever they may originate; and those assailants in ambush are hereby informed that in every succeeding edition of the work, I shall continue to hand down to posterity the infamy which justly attaches to the knaves and dishonest dealers who have been convicted at the bar of the Public Justice of rendering food deleterious to health.”

These are brave words because Accum underestimates the power of his hidden enemies. Their attack comes from an unexpected party: the venerable Royal Institution, where Accum worked between 1801-1803 under Director Humphry Davy. Before an unusual board meeting of the Royal Institution on December 21, 1820, Secretary Mr. Thomas Harrison reports [11]:

“In consequence of the report made by Mr. Sturt, the Assistant Librarian, to the Managers on the 5th of November last that a number of books, in the reading room, had been made imperfect by having several leaves and plates taken out of them … and that the books which he had discovered to be mutilated were books that Mr. Accum … was in the habit of reading. The Secretary had directed Mr. Sturt to have holes bored in the cupboard of the room adjoining the reading room for the purpose of watching more closely the persons who frequented that room.

“On the evening of the 20th of December, Mr. Sturt saw Mr. Accum enter the room, where he remained for nearly two hours, during which time he watched him very closely from the cupboard and had no doubt but that he had torn several leaves out of a volume of Nicholson’s Journal. Immediately after Mr. Accum had quitted the Institution … Mr. Sturt examined the books which he had seen in Mr. Accum’s hands and found that Parmentier’s Treatise on the Composition and use of Chocolate had been taken out of Nicholson’s Journal Volume 5, which he was positive had been entire the week before.

“Mr. Sturt requested a private hearing with the Sitting Magistrate, who issued a warrant to search the house of Mr. Accum, in Compton Street and sent thither Bishop and Nicholls, two officers with Mr. Sturt. The latter after a search of nearly two hours discovered a number of leaves which he identified as been torn out of books belonging to the Royal Institution. The officers brought Mr. Accum and the leaves before the Magistrate.”

According to the minutes of the meeting:

“The Magistrate after hearing the whole of the case observed that however valuable the books might be from which the leaves found in Mr. Accum’s house had been taken, yet the leaves separated from them were only waste paper. If they had weighed a pound, he would have committed him for the value of a pound of waste paper, but this not being the case he discharged him.”

The Royal Institution is not satisfied with the dismissal of the theft charge. On the 23rd of December 1820, they decide to bring a second court case, calculating that they will have a better chance of conviction.

This second indictment is for the felonious theft of 200 pieces of paper of the value of ten pence and 120 grams of paper with a value of four pence and is accepted. A trial date is set for April 5th, 1821. To be released, Fredrick Accum pays a bail of 200 pounds, and two of his friends, publicist Rudolph Ackermann and architect John Papworth each pay 100 pounds.

4.1 Flight from England

When a prominent personality like Accum is accused by a venerable institution like the Royal Institution, it causes a great hue and cry and much discussion among the public, which is fueled by Accum’s secret enemies. The rumor mill churns, and prejudices run rampant. The excessive malice and derision of the press especially wounds Accum.

Accum’s world is falling apart [12]. He doesn’t know what to do, is distressed, stops working, and becomes depressed. Some of his friends try in vain to settle the case out of court, other “friends” turn away from him. His former publishers no longer want to print his books. He sees only one way out: by the time the trial begins on April 5th, Accum has already left England.

4.2 Why a Trial?

Because of Accum’s flight, whether any damage occurred at all, or the what the extent of any damage was, remains unsettled by the courts. It remains baffling that the Royal Institution brought a second case with so much urgency when their own statements indicate that it was about the laughable loss of 14 pence.

It is suspected that external powers exerted pressure, but this cannot be proven. It is striking that the Assistant Librarian Mr. Sturt cut a hole in the wall at the behest of the Secretary of the Royal Institution. He is then not only present as the police search Accum’s house, but also finds and identifies the telltale pages there. In addition, Sturt makes all visits to government offices relating to the trial. For his dedication, Mr. Sturt is explicitly thanked for his “zeal, diligence, and intelligence in this matter” at a board meeting.

However, it is also well known that Accum is quite eccentric and is rough with his own books, tearing out pages when he wants to make a quick note. Some of his friends suspect that he may demonstrates the same childish behavior with the books of others without realizing it is wrong. It thus remains unclear the extent to which he contributed to the tragic developments that ended in his flight from England.

4.3 Forgotten

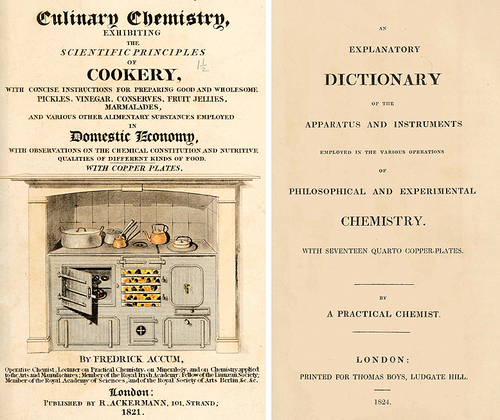

Fredrick Accum acquires a questionable reputation and becomes a persona non grata in England, eventually sinking into oblivion. The peak of this willful erasure is reached by one of his former publishers, who publishes a new edition of the beloved “Dictionary on Chemical Apparatus” in 1824 in which the author is not listed as Fredrick Accum, but rather “A Practical Chemist” [13] (see Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Right: Culinary Chemistry from 1821. Left: In the new edition of the “Dictionary on Chemical Apparatus” in 1824, the author is called “A Practical Chemist” instead of Fredrick Accum. (Images: links: wikimedia commons, public domain; right: Wellcome Library, public domain)

Only a few friends stand by Accum, including the German-British publisher Rudolph Ackermann, who speaks up for him as a bondsman prior to the trial. He convinces Accum to finish the manuscript he is working on, “Culinary Chemistry” (see Fig. 8) and adds a moving foreword:

“The publications which I have presented to the world, having been almost exclusively confined to subjects connected with the Fine Arts, I feel it in some measure incumbent on me to explain the cause of my having undertaken to be the publisher of this volume. It has arisen from a distressing event, in which its very ingenious, useful, and elaborate Author, happened to be involved.

“The work was in some degree of advancement, when the sudden and most unexpected misfortune to which I have alluded, threw him at once into a state of discouragement, that gave a check to all his exertions. I, who had known him long, and had every reason, from a most intimate acquaintance, to think well of him, both in his private as well as professional character, co-operated with many of his friends, some of whom are in the superior ranks of life, to encourage him in the renewal of his former energy—but I could succeed no further than in prevailing upon him to complete it.

“This little work on Culinary Philosophy, which promised to be highly useful in some of the leading objects of Domestic Economy. When it was ready for publication, the prejudice which had been excited against him, rendered his former publishers averse from presenting it to the public. I therefore felt myself under a kind of indispensable engagement—nor am I ashamed of it, as the work was brought to a state of publication by my interference, though out of my usual line of business, to become its publisher. I accordingly, under these circumstances, made it my own by purchasing the copy-right. Nor, from its scientific novelty, and promised utility, have I the least hesitation in presenting Mr. Accum’s Work to the Public.”

In this way, publisher Rudolph Ackerman rescues this culinary chemistry gem for posterity and chemists who love to cook can take joy in Accum’s appreciation of chemistry in the culinary arts [14]:

“The art of preparing good and wholesome food is, undoubtedly, a branch of chemistry; the kitchen is a chemical laboratory; all the processes employed for rendering alimentary substances fit for human sustenance, are chemical processes …. “

4.4 Return to Germany

In 1815, Accum became a corresponding member of the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin, Germany. This connection helps him in his integration, and in 1822 he is appointed Professor of Technical Chemistry and Mineralogy at the Royal Trade Academy and also named Professor of Physics, Chemistry, and Mineralogy at the Royal Building Academy in Berlin in 1824. In the course of this teaching activity, he writes the two-volume textbook “The Physical and Chemical Nature of Building Materials, their Selection, Properties, and Practical Use.”

In Berlin, he is no longer in the public spotlight, although he remains active. He is the driving force for the introduction of gas lighting in Berlin. With his connections to England, he helps Berlin’s boulevard “Unter den Linden” to be brightly illuminated in the neogothic style with 26 English gas lamps on September 20th, 1826.

In 1828, Accum has a prestigious house built at Marienstrasse 23 in the center of Berlin (see Fig. 10) [15], where he lives until his death. In his final years, he suffers from gout. The state of his health declines in early June of 1838 and he dies about 16 years after his return to Germany, on June 28, 1838, aged 69.

Figure 10. Friedrich Accum‘s house at Marienstrasse 23 in Berlin, Germany. (Image: Jörg Zägel, wikimedia commons cc 3.0)

His obituary in the October issue of The Gentleman’s Magazine [16] demonstrates how long preconceptions and misinformation about Accum persisted in England. His books were correctly quoted but the depiction of his departure from England was completely distorted:

“For many years he taught at institutions in Surrey and London. His career ended abruptly when it was discovered that he, in order to spare himself the effort of transcribing, damaged valuable books belonging to these institutions. He was then obliged to quit the country.”

This was a distortion of the facts.

5 Friedrich Accum’s Legacy

Accum was not an academic researcher, however, he earned our appreciation for his application of analytical chemistry in the study of foods. His pedagogical talents in presentations and publications are legendary and contributed greatly to the popularization of chemistry in English society in the early 19th century. Chemical historian C.A. Browne exults, “No author understood better than Accum how to convey the allure of chemistry to the public.”

His book, A Treatise on Adulteration of Food was a milestone in the history of food chemistry. Unfortunately, he could not benefit from the fruit of his work, because after his departure from England, the public lost interest in Accum and unfortunately also in the subject of food adulteration.

Criminal adulterators continued undisturbed and Accum’s work seemed to have no effect. Food adulteration was only discussed in medical journals and brave individuals, warned by Accum’s failure, only occasionally tried to take up this perpetually relevant topic.

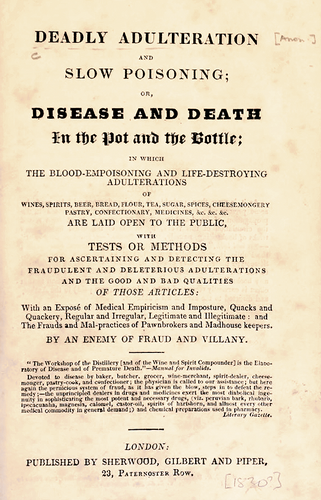

Fear of the adulterator lobby (publicans, brewers, pharmacists, etc.) was so great that the author known as An Enemy of Fraud and Villainy, an 1830 book with a title that alluded to Accum’s work, Disease and Death in the Pot and the Bottle, published it anonymously (see Fig 11) [17].

Figure 11. Title page of “Disease and Death in the Pot and the Bottle” by an anonymous “Enemy of Fraud and Villainy” (Image: wellcome collection public domain, wellcomecollection.org/works/j8jnvr38)

5.1 Blueprint for John Mitchell, Arthur Hill Hassall, and Others

It took until 1848 for English Chemist John Mitchell to bravely publish his book on The Falsifications of Food, and the Chemical Means Used to Detect Them under his full name [18]. He had found out that since Accum’s time, food was being even more egregiously and extensively adulterated. Accum’s warnings still applied.

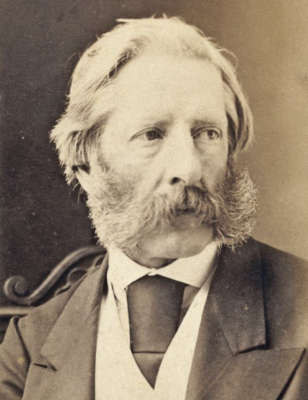

Based on these indications, Arthur Hill Hassall (1817–1894), an English doctor with a particular interest in hygiene and public health (see Fig. 12), investigated the current state of food adulterations in a series of publications and summarized his results in a report to the British Parliament [19].

In gathering his data, Hassall used the same approach as Accum, but significantly expanded the data he collected. The result of this tedious work was shocking. Practically all vinegar samples obtained were blended with sulfuric acid and contained toxic copper salts; coffee, bread, and confectionary were diluted and contaminated with poisonous heavy metal salts. Of 28 samples of cayenne pepper, only four (!) were authentic, 22 of these contained the red-brown, iron-containing mineral pigment called burnt Sienna, 13 contained lead-containing minium (lead tetroxide), and one sample contained cinnabar (HgS).

Figure 12. Arthur Hill Hassall (1817–1894). (Image: wellcome library, London, V0026521, cc 4.0)

In his report to the British Parliament, Hassall used Accum’s gambit of listing the suppliers of adulterated wares by their full names. He even went so far as to add their precise addresses as well (see extra info below).

Pigments in Various London Confectionary Around 1850

Pigments in Various London Confectionary Around 1850

See extra info

The yellow candied almonds sold by Mr. Blanchard, South Street, Manchester Square, contained poisonous amounts of lead chromate.

White sugar buttons with red spots sold by Mr. Hampton, Grafton Street, Soho, contained cinnabar.

The ginger palates sold by S. Berry, 21 Great Windmill Street, Haymarket, contained lead chromate in absolutely poisonous amounts.

Depending on their color, the sugar seeds sold by G. Reading, Church Lane, Whitechapel, contained Prussian blue, minium (lead tetroxide), or lead chromate.

The sugar seeds sold by W. J. Odell, Brick Lane 28, Spitalfields, contained Scheele’s green (copper arsenite), lead chromate, and verditer (basic copper carbonate).

The cake ornaments sold by F. Allen, High Street 117, Whitechapel, contained lead chromate, minium, cinnabar, and Scheele’s green in poisonous quantity.

Hassall illustrated his report with medical records. These proved, in agreement with Accum’s findings, that the primary victims of adulterated confectionary were children. In 1847, the Pharmaceutical Journal reported that on the 14th of September, three adults and eight children presented themselves at the Marylebone Infirmary Hospital. They suffered from severe vomiting and gagging, and their vomit was green. Upon questioning, it was discovered that one of the children had purchase green confectionary for two pence and distributed them. The symptoms appeared within 10 minutes of consumption. After administration of eggs and sugar stirred into fresh milk, the vomiting was so effective that the patients could all be discharged after two days. The publisher of the Pharmaceutical Journal added the following comments [20]:

“The pigment usually employed by confectioners for green ornaments, is the arsenite of copper, a fact which has been frequently published, with a caution respecting its dangerous properties. Notwithstanding the notoriety of this circumstance, confectioners appear to be quite reckless on the subject and sell the poison to children at so cheap a rate, that a whole family may be poisoned for two-pence! In the above case, if timely medical aid had not been at hand, eleven persons might have lost their lives in consequence.”

The extent of such, partially lethal poisonings finally led to legislative consequences as the Adulteration Act of 1860 was passed thanks to Hassall’s dedication. This first legislation proved to have little effect, and the Sale of Foods and Drugs Act was passed in 1875, which became an effective weapon against adulteration as amendments were added.

It is a relief to learn that although Accum has been forgotten by the English public, the next generation of experts in the second half of the 19th century used his methods as a blueprint for the development of superior food laws [21]. As well as benefitting consumers in Great Britain, other European countries and the USA were also spurred to take similar action.

5.2 Current Laws and Food Adulteration in the EU

Today, foods are among the most regulated consumer goods in the EU. The laws and regulations are extremely detailed and comprehensive. There are over 100 regulations about the production and labelling of foods.

Although this body of legislation may look very perfectionistic in detail, leading to occasional head shaking in industrial practice, it ensures safe food for the protection of the consumer. We need not fear poisoning with copper, arsenic, and lead today. However, this does not mean that adulteration no longer occurs. As in Accum’s time, cheating, mixing, and dilution in the name of profit continue today. However, adulterators have also learned and avoid easily detectable toxic additives.

The German Agricultural Society (Deutsche Landwirtschafts-Gesellschaft DLG) outlined the current state of food adulteration in a gripping brochure [22,23], which lists the current top ten.

Top Ten Current Food Adulterations

- Olive Oil: incorrect indication of source, mixing with old stock, mixing with soybean, corn, sunflower, hazelnut, or other oils.

- Fish: incorrect species, aquaculture sold as wild caught, soy protein added to processed fish dishes.

- Organic foods: Inclusion of conventionally cultivated products.

- Milk: Stretching with plant oils and water, mixing with foreign protein and substances included to appear as protein, such as melamine.

- Grains: incorrect type of grain, purity, false origin, method of cultivation, stretching with foreign substances in flours.

- Honey and maple syrup: Stretching with invert sugar or saccharose syrups, addition of sugar and water.

- Coffee and Tea: Coffee: origin, variety, stretching with roasted corn, stretching with malt or legumes. Tea: origin, variety, stretching with used tea leaves, mixing with dyed sawdust, stretching with worthless stems.

- Spices: Chili: stretching with marigold petals, sandalwood shavings, dyed grass, fibers from red beets or pomegranates, dying with yellow and red pigments.

- Wine: Origin; purity; vintage; addition of water, sugar, or ethylene glycol; false labelling.

- Fruit juice: Orange and apple juice: addition of other fruit juices, simulation of “fresh pressed” by addition of cloudy substances, dilution with water and sugar, addition of artificial fragrances or flavors, as well as dyes.

Writing up this top ten brings on a feeling of déjà vu, and Accum’s presence is tangible. If some readers are inspired by the fantastic idea of taking up Accum’s ideas, which are clearly still relevant, they should learn from this outstanding chemist and campaigner for consumer protection and imitate his prowess, perseverance, and incorruptibility.

We can also learn from his mistakes. On the one hand, sometimes large goals are more easily met in small steps; on the other, one should never tear pages out of library books because “they are books and therefore sacred”. (The original quotation is from “The Tin Drum” by Günter Grass: “Even bad books are books and therefore sacred.”)

Acknowledgement

My thanks to Dr. Gerhard Karger, GDCh, Frankfurt, Germany, who handed me this fascinating topic on a silver platter, and Dr. Hans Bauer, Berlin, Germany, who contributed with substantial suggestions and his constructive criticism of the manuscript.

References

[11] R. J. Cole, Ann. Sci. 1951, 7, 128.

[12] C. Bing, J. Nutrition 1966, 89, 3.

[13] An Explanatory Dictionaly of the Apparatus and Instruments emloyed in the Various Oerations of hilosohical and Exerimental Chemistry, J. Green, London, UK, 1824.

[14] Frederick Accum, Culinary Chemistry – The Scientific Principles of Cookery, with Concise Instructions for Preparing Good and Wholesome Pickles, Vinegar, Conserves, Fruit Jellies, Marmalades, and Various Other Alimentary Substances Employed in Domestic Economy, with Observations on the Chemical Constitution and Nutritive Qualities of Different Kinds of Food, R. Ackermann, London, UK, 1821.

[15] Bärbel Beetz, Über die Geschichte dieses Hauses: Berlin, Marienstraße 23, rüffer & rub Sachbuchverlag, Zürich, Switzerland, 2021.

[16] , Gentleman’s Magazine 1838, 10, 448.

[17] , Deadly adulteration and slow poisoning, or, Disease and death in the pot and the bottle, Sherwood, Gilbert and Piper, London, UK 1829?.

[18] J. Mitchell, Treatise on the Falsifications of Food, and the Chemical Means Used to Detect Them, Hyppolyte Bailliere, Paris, France 1848.

[19] A. H. Hassall, Food and its Adulterations, Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, London, UK, 1855.

[20] Mr. Hetley, Pharm. J. Trans. 1847, 7, 199.

[21] Über den Einfluss der Analytischen Chemie auf die Gesetzgebung im Nahrungsmittelbereich siehe: A. J. Ihde, J. Chem. Educ. 1974, 51, 295.

[22] Food Fraud – Lebensmittelverfälschungen: Möglichkeiten und Chancen zur Risikominimierung in komplex vernetzten Wertschöpfungsketten, DLG-Expertenwissen 11/2018, DLG e.V. Fachzentrum Lebensmittel, Frankfurt, Germany 2018.

[23] Jeffrey C. Moore, John Spink, Markus Lipp, Development and Application of a Database of Food Ingredient Fraud and Economically Motivated Adulteration from 1980 to 2010, J. Food Sci. 2012, 77(4), R118-R126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2012.02657.x

The article has been published in German as:

- Aufstieg und Fall des Fredrick Accum: Da ist der Tod im Topf,

Klaus Roth,

Chem. unserer Zeit 2024, 58(3), 156-168.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ciuz.202300034

and was translated by Caroll Pohl-Ferry.

Death in a Pot: From England’s Famous Chemist to Exiled and Forgotten – Part 1

Why did Fredrick Accum’s 1820 book about simple methods for detecting the adulteration of foods not make him a pioneer of consumer protection?

Death in a Pot: From England’s Famous Chemist to Exiled and Forgotten – Part 2

Let us take a closer look at the book about simple methods for detecting adulterations of food, published by Fredrick Accum in 1820

See similar articles by Klaus Roth published on ChemistryViews.org