The official name of the Summer Olympic Games is “Games of the (for example) XVIII. Olympiad”. An Olympiad is a period of four years, the time between two Olympic Summer Games. The Summer Olympic Games are always held in the first year of the Olympiad after which they are named.

We want to dive a little into the history and, of course, the chemistry of the marathon, a road race of over 40 km that traditionally concludes the Olympic Games. We hear about strychnine and brandy instead of water during the race, the first women in the marathon, how the distance went from about 40 km to exactly 42.195 km, hyponatremia from water intake, cannabinoid receptors, and much more.

Olympic Marathons – Tales From the First Marathon to Paris 2024

Athens, 1896

The ancient Olympic Games took place around the second millennium BC. They lasted five days and included running, duels, chariot racing, and a pentathlon. Toward the end of the fourth century AD, the Roman Emperor Theodosius banned all pagan cults. Since the Olympic Games were a religious event in ancient Greece, they were also banned.

The first modern Olympic Games were held in Athens, Greece, in 1896 on the initiative of the French Baron Pierre de Coubertin. At the end of the 1800s, very little was known about the ancient world, yet it was used as a myth to enhance the idea of modern sports and competition. Sports competitions were popular at that time and there were several national Olympic Games in Europe. Baron Pierre de Coubertin made the games international.

The 1896 Games in Athens included the first organized marathon, which became the highlight of the Games because it is the sport most closely associated with the ancient myth. According to the Greek legend, the messenger Pheidippides ran the approx. 40 kilometers from Marathon to Athens to deliver the news of the Greeks’ victory over the Persians and then collapsed. In the first marathon races, runners were also pushed to their physical limits and some even died.

The 1896 Games in Athens included the first organized marathon, which became the highlight of the Games because it is the sport most closely associated with the ancient myth. According to the Greek legend, the messenger Pheidippides ran the approx. 40 kilometers from Marathon to Athens to deliver the news of the Greeks’ victory over the Persians and then collapsed. In the first marathon races, runners were also pushed to their physical limits and some even died.

The first organized marathon took place on April 10, 1896. There were 17 runners; four of them were not from Greece. The winner was the Greek Spyridon Louis, who ran about 40 kilometers in 2 hours and 58 minutes, a sensationally good time.

A Greek woman, Stamata Revithi, also wanted to run the marathon, but she was denied entry because she was a woman. The next day, she ran the marathon alone, accompanied by the press, but when she tried to enter the stadium, she was also denied entry.

Women were not allowed to run the marathon until 1984, and only in 2012 were women allowed to compete in all sports for the first time. The first women participated in the Second Olympiad in Paris, France, in 1900, but only in sports such as tennis and golf, which were included in the games at that time.

Saint Louis, 1904

The Games of the third Olympiad were held in St. Louis, USA, in 1904 as part of the World’s Fair, which ran from May to October, and attracted very few foreign participants due to the high cost of travel from Europe.

The marathon was held on August 20, 1904. The course was unpaved, hilly, and very dusty, and the day was very hot. In those days, it was not recommended to drink during the race, so there was only one water stop on the course.

The winner was Thomas Hicks. But he was very lucky to make it to the finish line and survive. He was reportedly knocked unconscious several times along the way, and his supporters helped him a few times by rinsing his mouth with distilled water (see also below for more on why this is not a good idea). But it gets even better: At 27 or 28 kilometers, he was given a dose of strychnine (a strong poison) mixed with egg whites, and at 32 kilometers, he was given brandy to go with it. It was considered a legal doping agent at that time [1].

London, 1908

The marathon took place on July 24, 1908, in London during the fourth Olympic Games. It was again a very hot day, and for the first time the marathon course was 42 kilometers and 195 meters long, as it is today. How did this come about?

The start of the marathon was to be at Windsor Castle and the finish, as usual, at the stadium. The organizers measured everything and finally realized that their marathon route would not pass the Royal Box in the stadium. It was exactly 385 yards or 195 meters from their measuring point in the stadium to the Royal Box, which was then added to the distance.

This distance was kept the following games and in the 1920s, the length of the marathon was officially set at 42 kilometers and 195 meters (or 26 miles and 385 yards) to allow for comparisons between different races.

Paris, 2024

There are many exciting stories about the marathons of the various Olympic Games. But let us jump to Paris, to the streets of the 33rd Olympic Games in 2024. There will be two changes this year in the premier event of the Olympic Games. Normally, the men’s marathon closes the Olympic Games. This time, the Men’s Marathon will be held on August 10, 2024, at 08:00, 24 hours before the women’s marathon, which closes the Games.

There will also be a general public marathon, “Le Marathon Pour Tous”, on the Olympic course at the evening of August 10. Around 20,000 places will be allocated, with another 20,000 available for a 10-kilometer race [2].

And a Little Chemistry

Hitting The Wall – Or How to Maximize Energy

The energy for running a marathon comes from carbohydrates consumed and converted into glycogen by the liver and stored in the muscles. Runners are able to store enough glycogen for about 30 km of running.

The energy for running a marathon comes from carbohydrates consumed and converted into glycogen by the liver and stored in the muscles. Runners are able to store enough glycogen for about 30 km of running.

When glycogen is depleted, the body burns fatty acids, the building blocks of fat in our bodies. This can cause dramatic fatigue known as “hitting the wall.” Fatty acids are broken down into ketones and the pH drops. To get rid of the ketones, more urine is produced, causing dehydration which can be dangerous.

Training aims to maximize glycogen efficiency and reduce this fatigue. Runners often use carbohydrate-based energy gels to maintain energy levels during the race. Alternatives to gels include various forms of concentrated sugars and foods high in simple carbohydrates that can be digested easily.

To break down glucose effectively to H2O and CO2, oxygen is needed. This so called aerobic respiration is approx. 20 times more efficient than anaerobic respiration. Anaerobic respiration is better suited for short and fast activities such as sprinting.

Training increases the ability of the body to take in O2 and the ability of the cells to use it. However, when the aerobic respiration rate drops, the cells break down glucose into lactic acid. While it has long been thougth that lactic acid causes muscle soreness, its high concentration actually disrupts biological processes. This disruption prompts the brain to signal the body to slow down, resulting in the sensation of intense muscle pain.

Is It Possible to Drink Too Much Water?

Drinking water is important, as it keeps the body cool when you sweat. The liquid water on the skin evaporates, turning into water vapor and the energy for this comes from body heat. Sweat also gets rid of salt, which is why sports drinks contain sodium chloride, calcium chloride, potassium phosphate, and other salts, collectively known as electrolytes.

When you drink water, it moves from the stomach through the intestines into the blood plasma, and from there it is quickly distributed throughout the body. The body can handle significant amounts of water because the kidneys efficiently regulate the water and electrolyte balance, excreting excess water as urine [3].

However, when water intake exceeds the kidneys’ ability to expel it and it is not released as sweat, the body swells, and the concentrations of all dissolved substances decrease, reducing osmotic pressure. Of special importance for our water and electrolyte balance is the concentration of sodium ions in the extracellular fluids (e.g., blood plasma, lymph fluid, cerebrospinal fluid). This condition is called hyponatremia, which can result in serious complications such as brain swelling [3].

Out of scientific curiosity, many have attempted to consume large amounts of water to measure the resulting changes in blood pressure, pulse, urine output, and other factors. In 1916, the British physiologist John Gillies Priestley drank three liters of water in a short period of time. He excreted the same amount as urine within a few hours, at a rate of up to 1.2 liters per hour. In his publication, he reported no health-related side effects [4].

In October 1983, at the American Medical Joggers Association’s annual meeting, a 24-year-old medical student and a 45-year-old physician participated in an ultramarathon event. An ultramarathon is a run that is longer than the traditional marathon length; various distances are run. Both exerienced marathon runners followed the advice to drink 300 to 360 mL of liquid every 1.6 km. This reulted in each to consume over 20 liters during the race.

They finished in a severely disoriented state and were diagnosed with water poisoning due to low sodium levels. The 45-year-old received a hypertonic salt solution intravenously and recovered quickly. The 24-year-old was given an isotonic solution, suffered severe complications, and remained hospitalized for five days [3].

Why Would You Run a Marathon?

Well, running into the packed Olympic Stadium at the end of the race must be amazing. But not many get to experience that moment.

Well, running into the packed Olympic Stadium at the end of the race must be amazing. But not many get to experience that moment.

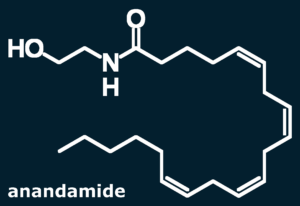

But there is the “runners high”. The euphoria known as a “runner’s high” might be due to the brain’s endocannabinoid system, which also responds to δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the active ingredient in cannabis. Anandamide (pictured), also known as N-arachidonoylethanolamine, is found in runners’ blood. It acts on the same receptors as the psychoactive THC and leads to increased dopamine levels, resulting in the euphoric feeling.

References

[1] Klaus Roth, Strychnine and Brandy in a Marathon (Part of Strychnine: From Isolation to Total Synthesis – Part 1), ChemistryViews 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/chemv.201500031

[2] ClubParis2024 (accessed July 22, 2024)

[3] Klaus Roth, Can Too Much Water Be Toxic?, ChemistryViews 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/chemv.201700047

[4] J. G. Priestley, The regulation of the excretion of water by the kidneys, J. Physiol. 1916, 50, 304. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1921.sp001974

Source

- Richard Hemmer, Daniel Meßner, Eine kurze Geschichte der Olympischen Spiele (der Neuzeit), Geschichten aus der Geschichte GAG242, Podcast May 2020.

Also of Interest

A compilation of articles on chemistry related to sports