The EuChemS Chemistry Congress (ECC) is the largest European chemistry congress. It is held every two years in a different European country. Previous editions have been held in Budapest, Turin, Nuremberg, Prague, Istanbul, Seville, Liverpool, and Lisbon.

In 2024, ECC9 was held in Dublin, Ireland, from July 7–11, 2024. It was jointly organized by EuChemS and the Institute of Chemistry Ireland (ICI), under the leadership of ICI President Pat Guiry. The ICI is the professional body representing chemists in Ireland.

The Venue

The convention center was located on the banks of the River Liffey in Dublin’s former Docklands, now a financial district, and next to the Samuel Beckett Bridge, designed by renowned architect Santiago Calatrava (*1951) to resemble a harp, the national symbol of Ireland, representing the legacy of Celtic culture. The Dublin Convention Center was designed by Irish architect Kevin Roche (1922–2019) and opened in 2010. Its glass front, especially from the top floor, offers a great view of Dublin and the Wicklow Mountains beyond. But that’s just a side note as this is about chemistry, not sightseeing.

Samuel Beckett Bridge. (Photo © V. Koester)

The Talks

From what I heard, besides many high-quality talks, the two talks by Nobel Laureates Frances Arnold and David MacMillan were particularly remarkable for many conference attendees. Hearing a Nobel Laureate talk about their research is always fascinating. Still, in this case, they did an excellent job of explaining complicated things in a very clear and entertaining way.

In the boxes below you will find short summaries of a few selected talks. Of course, there were many, many more great and interesting presentations at the conference – a total of 534, plus eight plenary sessions and eight European Younger Chemists’ Network (EYCN) sessions, posters, exhibitors, and the opportunity to network with some 1650 participants.

Talk by Frances H. Arnold

“We can read DNA, we can write DNA, but we still do not know how to compose it.” If we want to make a new enzyme or make an existing one work under non-natural conditions, we have to be able to compose that sequence of DNA that encodes that capability. Nature has done this through evolution, through mutation and natural selection, and over a long period. Similar to this, Frances Arnold and her team are designing new enzymes. They use evolution to randomly mutate the DNA towards a desired aim. The process is similar to the selective breeding of plants and animals by which humans have modified the biological world to serve our needs. “We have done this in an iterative process without understanding the underlying mechanism.”, Arnold said. In 2016, Frances Arnold and coworkers created, for example, an enzyme that could create a Si–C bond [1]. Using cytochrome c from Rhodothermus marinus, they improved the reaction to be 15 times more efficient than industrial catalysts. Their recent work uses directed evolution, simulation, and machine learning to optimize and develop enzymes, applied to biocatalysis in pharmaceuticals, biofuels, sensors, and diagnostics.

First Enzyme to Break a Si–C BondIn a recent publication [2], Frances Arnold and her team identified and evolved a cytochrome P450 enzyme to efficiently hydroxylate and cleave the carbon-silicon bonds of methylsiloxanes. These are human-made organosilicon compounds that are resistant to biodegradation and may bioaccumulate. Their enzyme is the first to break a silicon-carbon bond, including both linear and cyclic forms.

Beyond ScienceIn addition to her research, Frances Arnold shared her scientific journey and role as an advisor to the Biden administration, emphasizing the importance of promoting values such as “hope over fear, unity over division, science over fiction, and truths over lies.” She also portrayed herself in an episode of the TV show The Big Bang Theory.

References[1] S. B. Jennifer Kan, Russell D. Lewis, Kai Chen, Frances H. Arnold, Directed evolution of cytochrome c for carbon–silicon bond formation: Bringing silicon to life, Science 2016, 354(6315),1048-1051. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah6219 [2] Nicholas S. Sarai, Tyler J. Fulton, Ryen L. O’Meara, Kadina E. Johnston, Sabine Brinkmann-Chen, Ryan R. Maar, Ron E. Tecklenburg, John M. Roberts, Jordan C. T. Reddel, Dimitris E. Katsoulis, Frances H. Arnold, Directed evolution of enzymatic silicon-carbon bond cleavage in siloxanes, Science 2024, 383(6681), 438-443. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adi5554 |

Other Captured Moments

During the opening ceremony, the 2023 EuChemS Award for Service was presented to Robert Parker, former CEO of the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC). Amilra De Silva, Professor at Queen’s University Belfast, Ireland, gave a plenary talk on supramolecular chemistry. (Photos © Vera Koester)

Gianluigi Albano (left) of the University of Pisa, Italy, was awarded the European Young Chemist’s Award (EYCA) Gold Medal (Photo from X). Hartmut Frank (middle), Professor at the University of Bayreuth, Germany, received the 2023 EuChemS Award for Service from EuChemS President Angela Agostiano, Professor at the University of Bari, Italy (Photo © Karin J. Schmitz/GDCh). Avelino Corma, Professor and founder of the Instituto de Tecnología Química (CSIC-UPV) in Valencia, Spain, received the EuChemS Gold Medal (Photo from X).

David A. Leigh, Professor at the University of Manchester, UK, has received the August Wilhelm von Hofmann Medal 2024 from the German Chemical Society (GDCh) for his pioneering achievements in the field of nanoscience as well as his tireless efforts as an ambassador for chemistry. He received the medal and certificate from the President of the GDCh, Stefanie Dehnen, Executive Director of the Institute of Nanotechnology at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Germany.

The German Chemical Society (GDCh) team at their booth: (left to right) Tom Kinzel, designated Managing Director, Karin J. Schmitz, Director of Public Relations, Jasmin Herr, Management Executive Officer, Hans Georg Weinig, Director Education, Career and Science. And of course, Erlie, the GDCh mascot, cannot be missing. (Photos © Karin J. Schmitz/GDCh)

Speakers and chair of the “How and Why You Should Engage in Science Policy” session. (Photo © EYCN)

From left: Helen Pain, CEO of the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC), Frances H. Arnold, Professor at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), Pasadena, CA, USA and Nobel Laureate, Floris Rutjes, Professor at Radboud University Nijmegen, The Netherlands, and Vice President of EuChemS, Maximilian Menche, EYCN and BASF.

European Young Chemists’ Network (EYCN) team members and others meet with Professor ChemChicken at the EuChemS booth. (Photo © EYCN)

From left: Monja Schilling, Helmholtz Institute Ulm, Germany, Marie-Désirée Schlemper-Scheidt, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland, Noah Al-Shamery, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, João Borges, University of Aveiro, Portugal, Patrick Fritz, University of Fribourg, Switzerland, Maximilian Menche, BASF SE, Ludwigshafen, Germany, Thomas Vranken Hasselt University, Belgium, Miguel Steiner, ETH Zürich, Switzerland, Fernando Gomollón-Bel, Agata Communications, UK, Federico Bella, Politecnico di Torino, Italy, Manuel Souto, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Spain, Aurora Walshe, Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC), UK.

American Chemical Society (ACS) and GDCh group photo. (Photo © Karin J. Schmitz/GDCh)

From left: Hans Georg Weinig, Director Education, Career and Science, Tom Kinzel, designated Managing Director GDCh, Mary K. Carroll, President ACS and Professor at Union College (Schenectady, New York), USA, Stefanie Dehnen, President GDCh and Executive Director of the Institute of Nanotechnology at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Germany, Albert G. Horvath, CEO ACS, Peter Schreiner, Professor at Gießen University, Germany and former President GDCh, Jodi Wesemann, Director of Strategy and Society Programs for ACS, Christina I. McCoy, Manager, Global Relations, Member Engagement ACS, Adelina Voutchkova, Director Green Chemistry, Safer Chemical Design, Catalysis ACS.

Talk by David LeighDavid Leigh, Professor at the University of Manchester, UK, accompanied his lecture on molecular machines with magic tricks involving rings, scarves, and newspapers.

Ratchet Mechanisms in ChemistryDavid Leigh’s work focuses on ratchet mechanisms, which control the movement of molecules in a directed way, rather than relying on random motion. There are two principal types applicable to chemistry:

First Autonomous Chemically Fueled Synthetic Molecular MotorThe first autonomous chemically fuelled synthetic molecular motor was presented in 2016 [1,2]. David Leigh describes a system where a small macrocycle moves continuously and directionally around a larger molecular track, powered by the chemical fuel fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl chloride (Fmoc-Cl). The mechanism is illustrated by a Wollit and Gromit movie [2]. The motor operates as long as unreacted fuel remains, achieving directionality through asymmetric reaction rates that prevent the macrocycle from reversing direction. Specifically, the chemical fuel reacts faster when the macrocycle is farther from the reactive site and slower when it is closer. This difference in reaction rates creates a bias that propels the macrocycle in one consistent direction, preventing it from moving backward and ensuring continuous, directional motion around the track.

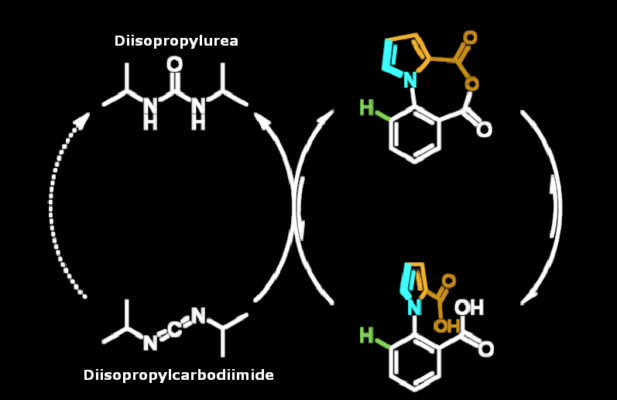

First Autonomous Unidirectional 360° Single-Bond RotationIn 2022, the Leigh group developed an autonomous single-bond rotary motor that operates through an information ratchet mechanism. 1-phenylpyrrole 2,2′-dicarboxylic acid is a catalysis-driven motor that can continuously convert a chemical fuel into energy to induce repetitive 360° directional rotation of the two aromatic rings around the covalent N–C bond that connects them [3]. The biaryl motor features carboxylic acid groups on each ring that cannot pass each other via rotation around the C−N biaryl bond; instead, interconversion of atropisomeric conformations occurs through rotation in the opposite direction. When fueled with a carbodiimide, however, a cyclic anhydride forms, enabling the carboxyl groups to pass each other through a low-energy ring flip, allowing effective rotation past each other.

Applications and PotentialDavid Leigh’s research has shown that these mechanisms can be applied not only to synthetic molecular machines and motors but also to various chemical exchange processes. This is leading to the creation of advanced functional molecules and the first examples of molecular robots. Using artificial molecular ratchets for practical applications is still early in development. They have been integrated into various materials such as surfaces, gels, and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). Light-driven motors have shown potential in twisting polymer chains to contract gels and disrupt cell membranes, yet broader applications interfacing with bulk materials remain unexplored, and molecular motors have primarily functioned as switches. Exploring synthetic ratchets interfaced with membranes holds promise, mimicking biological machines that pump species across membranes and maintain non-equilibrium states. Challenges persist in their robustness and versatility compared to biological counterparts. The recognition of molecular ratchet mechanisms in biology, and their invention in synthetic systems, is proving significant in areas as diverse as supramolecular chemistry, systems chemistry, dynamic covalent chemistry, DNA nanotechnology, polymer and materials science, molecular biology, heterogeneous catalysis, endergonic synthesis, the origin of life, and many other branches of chemical science.

References[1] Miriam R. Wilson, Jordi Solà, Armando Carlone, Stephen M. Goldup, Nathalie Lebrasseur, David A. Leigh, An autonomous chemically fuelled small-molecule motor, Nature 2016, 534, 235–240. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18013 [2] Cracking Nanomotor, Gromit!, Leigh group website (accessed July 17, 2024) [3] Stefan Borsley, Elisabeth Kreidt, David A. Leigh, Benjamin M. W. Roberts, Autonomous fuelled directional rotation about a covalent single bond, Nature 2022, 604, 80–85. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04450-5 [4] Stefan Borsley, David A. Leigh, Benjamin M. W. Roberts, Molecular Ratchets and Kinetic Asymmetry: Giving Chemistry Direction, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202400495 |

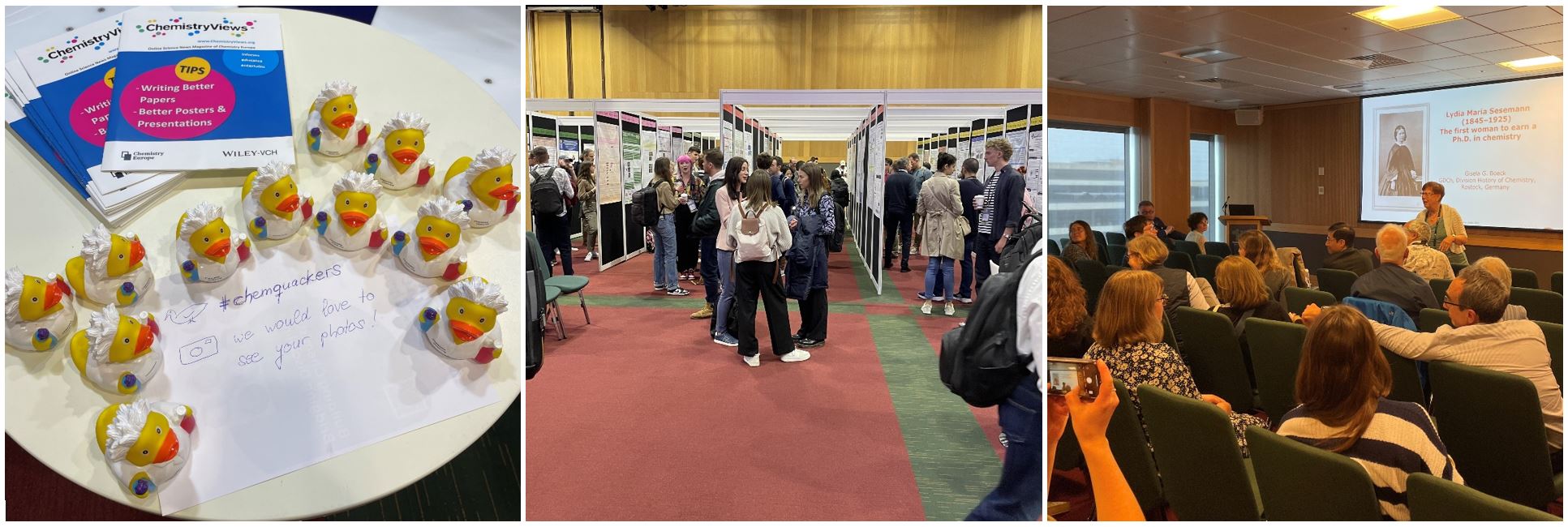

Some Chemquackers traveled with us to Dublin. The photo in the middle was taken during a coffee break in the exhibition and poster hall. The picture on the right shows Gisela Boeck, Professor at the University of Rostock, Germany, and Chair of the GDCh History Division, during her talk on Lydia Sesemann, the first woman to receive a Ph.D. in chemistry. (Photos © Vera Koester)

EYCN Program: Some of the speakers: Monja Schilling, Helmholtz Institute Ulm, Germany, Pilar Goya Laza, Professor at Instituto de Química Médica, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC, Spanish National Research Council), Madrid, Spain and former EuChemS President, Vera Koester and Anne Nijs, both Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany, and two snapshots of sessions. (Photos © Maximilian Menche)

Some more snapshots: In the first, João Borges, Senior Researcher at the University of Aveiro, Portugal, Vera Koester, Editor ChemistryViews, and Juliana Vidal, Program Manager at Beyond Benign, Canada/Brasil.

Some more snapshots: In the first, João Borges, Senior Researcher at the University of Aveiro, Portugal, Vera Koester, Editor ChemistryViews, and Juliana Vidal, Program Manager at Beyond Benign, Canada/Brasil.

In the middle, speakers and chair of the “Road to Success” session in the EYCN program. (Photo © Fernando Gomollón Bel)

From left: Fernando Gomollón Bel, Agata Communications, Cambridge, UK, Vera Koester, ChemistryViews, Christoph Schotes, Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany, Giulia Moncelsi, Elsevier-Reaxys, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, Nessa Carson, AstraZeneca, Macclesfield, UK, and Maximilian Menche, EYCN and BASF SE, Ludwigshafen, Germany.

Last but not least, a picture of the statue of James Joyce on North Earl Street, also known as “the prick with the stick” to Dubliners. James Joyce’s final work, “Finnegans Wake,” written over 18 years and published in 1939, reflects his realization that physics, like his use of language, begins to blur as one moves into the microscopic world. This concept fascinated physicist Murray Gell-Mann so much that when he discovered the fundamental particles of matter in 1965, he named them “quarks,” after a quote from Finnegans Wake: “Three quarks for pattern-marking!” (Photo © Vera Koester)

Chemistry EuropeFounded in 1995, Chemistry Europe is an association of 16 European chemical societies, all members of EuChemS. It publishes a family of high-quality scientific chemistry journals covering a wide range of disciplines, as well as the science news magazine ChemistryViews. The EuChemS Chemistry Congress, along with the Chemistry Europe Councils and Representatives Meetings, is one of the main meeting places for members of Chemistry Europe.

Flagship Journal – ChemistryEuropeAt a Chemistry Europe Mini-Symposium Luisa de Cola, Professor at Università degli Studi di Milano Statale, Italy, and Lars C. Grabow, Professor at the University of Houston, TX, USA, and both editors of the new, high-impact journal ChemistryEurope, reported on their research.

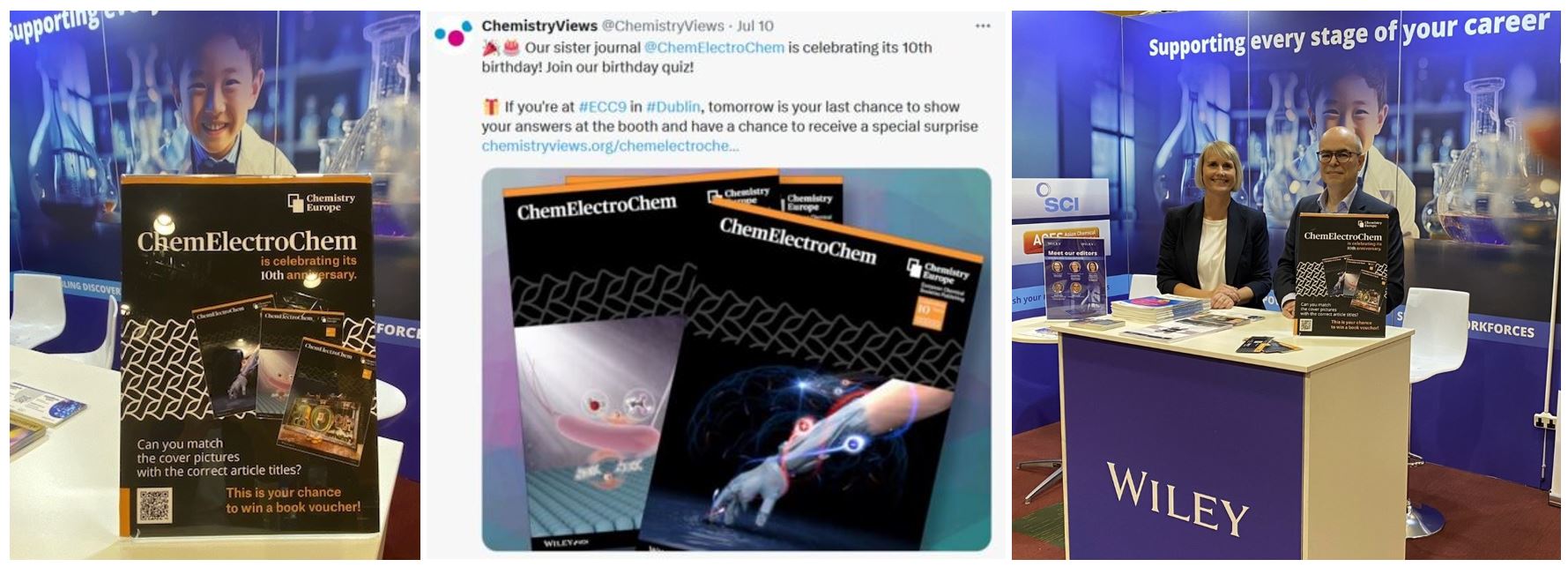

ChemElectroChem Quiz in ChemistryViewsTo celebrate the 10th anniversary of ChemElectroChem, a quiz was held at the Wiley booth and on ChemistryViews. Many participants had fun trying to match cover images and article titles from the journal and win a prize at the booth. The quiz runs until July 21, 2024. A book voucher will be raffled among all participants. So, join in quickly 😊

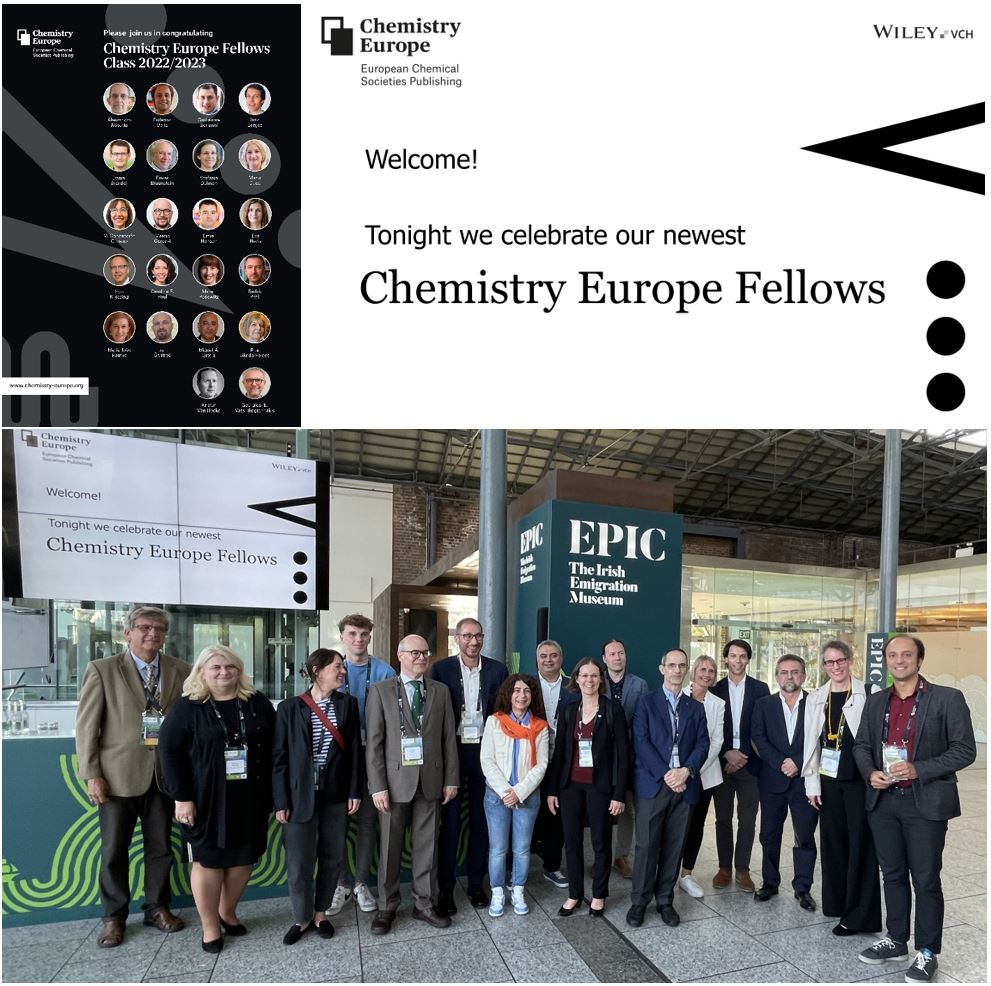

Fellows ReceptionThe Chemistry Europe Fellows Reception took place in the nearby Epic Museum, a museum about immigration, with about 60 invited guests. Every two years, Chemistry Europe recognizes innovative ideas and outstanding support for its publication activities by awarding the title of Chemistry Europe Fellow. The European Chemical Societies participating in Chemistry Europe award their Fellows with certificates and trophies at a national meeting. Traditionally, the entire class of new Fellows is also honored with a reception at the ECC. And we love celebrating with our authors, readers, supporters, and, in the meantime, many friends. Thank you all for the great party and support! The next round of Fellow nominations will begin next spring. We are currently accepting nominations for the Chemistry Europe Award.

|

Next EuChemS Chemistry Congress

The 10th EuChemS Chemistry Congress (ECC10) will be hosted by the Royal Flemish Chemical Society (KVCV) and will be held in Antwerp, Belgium, from July 12 to 16, 2026.

I am already looking forward to seeing everyone again and meeting many new people.

Also of Interest

Quiz/Game: ChemElectroChem Anniversary Brain Teaser

Quiz/Game: ChemElectroChem Anniversary Brain Teaser

Can you match the cover pictures with the correct article titles? Then you might win a nice book!

Meeting the 2018 Chemistry Nobel Laureate Frances Arnold and learning about her research field

Compilation of statements by Presidents of chemical societies (ACS, GÖCH, RACI, RSC, SCI) on the GDCh’s motto “Rethinking Chemistry”

Highlights of the Young Chemists’ Program at the 8th EuChemS Chemistry Congress

Event Highlight: Discussing Chemistry with Friends in Europe

8th EuChemS Chemistry Congress (ECC8) brought scientists from Europe and around the world to Lisbon, Portugal

Chemistry Europe honors new Fellows for their exceptional support and contributions to the European joint publishing venture

The prize was awarded to Frances H. Arnold, George P. Smith, and Sir Gregory P. Winter for their work on directed evolution

The prize was awarded to Benjamin List (Germany) and David MacMillan (USA) for the development of asymmetric organocatalysis

Ohter Publications

- ECC9 Concludes, EuChemS Magazine July 2024.

Frances H. Arnold, Professor at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), Pasadena, CA, USA, said, she fell in love with enzymes because they can do chemistry better than human chemists and do it cleanly and effectively with only a few waste products.

Frances H. Arnold, Professor at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), Pasadena, CA, USA, said, she fell in love with enzymes because they can do chemistry better than human chemists and do it cleanly and effectively with only a few waste products.