The German National Research Data Infrastructure (NFDI, Nationale Forschungsdateninfrastruktur) initiative and its consortia, such as NFDI4Cat, aim to create an interdisciplinary network that enables the sustainable handling of research data according to the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles.

Dr. Andreas Förster serves as the Executive Director of DECHEMA e.V., Frankfurt, Germany, and is also the spokesperson and coordinator of NFDI4Cat. Dr. Sara Espinoza is the Project Coordinator of NFDI4Cat at DECHEMA. With Dr. Vera Koester for ChemistryViews, they discuss the goals and working methods of NFDI4Cat, the benefits it offers to researchers in academia and industry, and the transformative impact of FAIR data sharing on catalysis research.

Could you please give an introduction to NFDI4Cat and explain its main goals?

Andreas Förster: NFDI4Cat is a project funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) to digitalize the research data lifecycle in catalysis and catalysis-related sciences. The main goal of NFDI4Cat is to enhance data accessibility, facilitate the development of new catalysts, and unite the catalysis community.

To achieve this, the project focuses on collecting data in the lab and organizing it using well-defined categories along with relevant metadata. The data is then stored in a manner that complies with the FAIR principles, ensuring it is findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable. This allows not only researchers within the same lab but also those from other labs and institutions to access and use the data, fostering collaboration and innovation across the entire catalysis community.

NFDI4Cat is part of a larger funding program by the DFG, including a total of 27 consortia running for five years. There is a possibility of extending this project for an additional five years. Currently, in its midterm, NFDI4Cat started on October 1, 2020.

Do you cooperate closely with other projects such as NFDI4Chem?

Andreas Förster: Sure. NFDI4Chem is a very good example, we are very intensively cooperating with them. Examples of collaboration include joint training events such as our upcoming programming course: Python Computing 4 Chemists (and others). Other examples are, for instance, NFDI4Ing, which is the National Research Data Infrastructure for Engineering Sciences, and FAIRmat, a consortium that focuses on condensed-matter physics and the chemical physics of solids.

Sara Espinoza: NFDI is active in trying to keep all consortia working together, as we all are facing the same challenges. There are regular meetings where we work together within different sections, and there are specific topics where we all have to work together, allowing for more communication between various NFDIs.

We have also several events where we try to cooperate, for example, in May, NFDI4Chem and NFDI4Cat held an event with Pedro Mendes from the Research Data Alliance (RDA). RDA is a global research community organization aiming to facilitate open data sharing.

What are the benefits of NFDI4Cat for scientists in the catalysis community?

Sara Espinoza: There are different positive aspects. It depends on the individual’s perspective. From the perspective of scientists, there are several advantages. When a scientist publishes a paper, a significant amount of data generated before and after the publication often remains unused. NFDI4Cat has the advantage of storing this ‘unused data,’ making it easier to find and cite in the future, thereby promoting its reusability.

For new researchers joining an institution, everything becomes easily accessible. They no longer need to spend time searching and asking others about previous work. Instead, they can simply go and see what has already been done and what is happening.

As our infrastructure develops further, our goal is to foster data sharing among researchers, encouraging open communication and collaboration. This means that scientists can benefit from improved collaboration and more open communication.

For funding agencies, the advantage lies in expanding the impact of their investment. Previously, experiments that weren’t published or weren’t made available for everybody can now be accessed by others, ensuring that valuable data is not lost. This allows researchers to retrieve and use the data when needed.

Andreas Förster: I think ensuring that the data is well-defined and universally usable is a real advantage for researchers and, ultimately, this approach leads to catalyst or process development based on comprehensive data analysis.

How do you make sure the data you collect is correct?

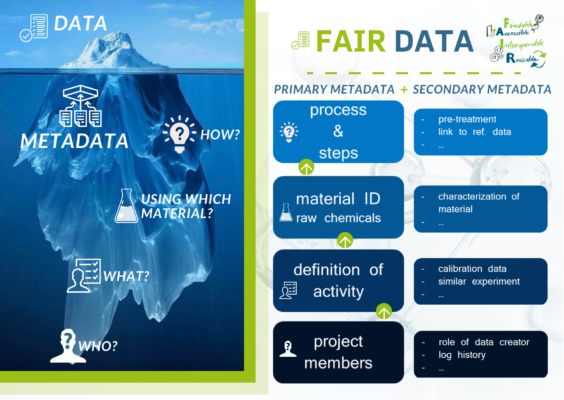

Sara Espinoza: This is one of the ongoing discussions we are having. Our focus is on ensuring a shared language and enabling the use of ontologies. A first version of a vocabulary guideline has been created.

Specifically, we aim to determine the minimum amount of information required for scientists to trust a data source. The idea is to provide a minimal set of metadata that enables scientists, particularly those using raw data, to decide if this data is good or not. By ensuring all the necessary information is available, individuals can make informed decisions based on the provided information.

Can you say a few words on ontology?

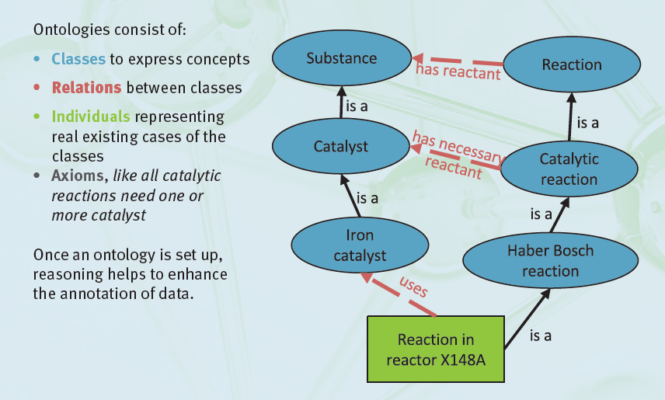

Sara Espinoza: That is always the first question we are asked. In the context of research data, ontology is a way to describe knowledge in a way that humans as well as computers can understand. Essentially, an ontology defines concepts, relationships, and properties within a particular domain, offering a formal and structured representation of knowledge. This structured framework of information makes data integration and interoperability easy and enables better understanding and analysis of complex relationships.

Figure 1. Schematic explanation of ontology. © Alexander Behr/Hendrik Borgelt

Andreas Förster: It is interesting that you address this question of what ontology means. The same question is also raised by researchers who are active in catalysis. Only a small percentage is familiar with ontologies and their description. This highlights the importance of NFDI4Cat’s goal to raise awareness of these concepts which are developing right now. These approaches, as well as other research management methods and tools, will be critical for the future of catalysis.

The DFG currently tries to make it mandatory for projects and publications to provide data according to the FAIR principles. However, most researchers are unaware of this requirement, although it will be essential for future research in catalysis and other fields. NFDI aims to increase awareness within the community, disseminate knowledge, and develop tools together with the community.

Sara Espinoza: The crucial aspect of NFDI is that everything is established by experts to ensure consistency, but it also needs to be accepted by the community.

What are the first steps you are taking here?

Sara Espinoza: To create ontologies and establish a shared vocabulary, we started by examining the different words people use to describe similar concepts. We aim to develop guidelines so that at least in the catalysis community everybody uses the same language. This shared language serves as the starting point for creating ontologies and allowing computers to also understand and interpret the information effectively.

Andreas Förster: Before data can be shared, it must be captured and stored and we have to define the right way to do it. That’s happening simultaneously, and it is another challenge, convincing even young researchers to use electronic laboratory notebooks (ELNs) and properly store these data. An ELN is a digital platform or software that replaces traditional paper laboratory notebooks and streamlines the process of recording, organizing, and managing scientific research data.

However, in practice, researchers often continue to use traditional handwritten notes, or sometimes ELNs do not interface with each other or other repositories. So, first and foremost, we must persuade researchers to use and preserve data correctly.

We/NFDI4Cat have been looking at some of the existing ELNs, at how they fit the needs of different research groups, which are the best, what are the capabilities, and what are the drawbacks. Our goal is not to provide a single tool for all research groups but to have a set of recommended ELNs that can be used by the different research groups and that meet the overall goal of delivering FAIR reseach data.

To do so, we have to agree on a common set of ontologies and standards, as Sara mentioned before. Metadata refers to information about the data itself, providing additional details or context. For example, it may include parameters like temperature or pressure. We need to make sure that this is stored in a consistent way and can be read by the different tools which will exist. This is the main purpose and ideally, this is also in agreement with other consortia such as the materials-developing community.

Figure 2. Schematic explanation of metadata. © Mohammad Khatamirad and Sara Espinoza

The goal of metadata is to ensure that experiments are conducted accurately and can be repeated reliably?

Andreas Förster: Yes, metadata is the solution for this.

Sara Espinoza: That is one of the reasons why we are using a community-driven approach. We try to collect use cases from the community, which enables us to identify the necessary steps involved in each different process in catalysis research. By doing so, we learn what kind of metadata is needed. For example, if certain information, like the amount of liquid used, is not provided, the metadata will be considered incomplete and will not meet the established standards. In this way, through the use cases and the definition of the standards, the users can decide which data is trustworthy and complete.

Currently, we are actively collecting the use cases. To do this, we ask researchers to share with us their experimental methods, as provided in academic papers, for example, and we talk to scientists about processes or methodologies that they use on a daily basis. These aspects are often forgotten and not listed properly.

Andreas Förster: If a research group wants to share some methods of their research, they are invited to test our tools with their data. It’s not only that we get the data and then we work with this, but working with us involves getting insights such as: “Yeah, this works, we have tested this,” or “You should use our tools because they are more suitable for your needs.” Also, the groups get feedback such as, “If you do this and that in this way, you should also measure this and that, otherwise you will not cope with the future needs.” I think this is a good opportunity to develop this field together.

When you say that the data is stored, it is not necessarily shared with everyone?

Andreas Förster: Exactly. In the future, it could also be the case that industry is providing part of its data into our knowledge base. Of course, it is necessary that the intellectual property (IP) behind it is protected and that the owners of the data can decide with whom they want to share what.

In my opinion, sharing data is of great benefit to society as a whole. We can make catalysis more efficient, we can improve new catalyst development, and this can be done faster. But, of course, the needs of the researchers from industry and universities who have developed these data must be respected. There is a group within NFDI4Cat that is trying to propose a model of how data can be published, it’s called the cool-off model [1]. This means that initially only the organization that prepared the data will have access to it. After a certain time, the group will be expanded and after another time, it can be fully opened. This is just one possible model that we are currently discussing.

Sara Espinoza: Our motto is: as open as possible and as restricted as necessary. It is important to work toward this cultural change to show people that there is nothing wrong with sharing data. I think this is a challenge that all the different NFDIs are facing together.

Probably. As we move further towards digitalization, I also believe that it is important for people to change their attitude because those who have access to extensive data resources will have a significant advantage over others.

Sara Espinoza: We are trying to transform research and nobody can do it alone.

You always emphasize the close cooperation with the community. How do you attract scientists to get involved?

Sara Espinoza: We are currently working on a reward model for data sharing. How can we really get researchers to actively and willingly share the data that they’re working on? There’s also been some discussion about some kind of point system for people who really share their data and so on.

Andreas Förster: Publishers can play a role, of course. They can require that an article could only be published if the data is accessible. Another approach, of course, is funding organizations like the DFG. They could demand that FAIR data is published.

Sara Espinoza: We work very closely with the journal ChemCatChem. Together, we came up with the idea of the Digital Chemist Award. We want to find interesting methods and software tools that make it easier to manage research data because that’s usually the biggest problem or challenge when we talk to scientists. They think it means so much extra work, and they don’t want to share their data because of it.

What is currently your biggest challenge?

Andreas Förster: Of course, there are scientific or organizational challenges like developing ontologies but this is manageable, and we have good experts in our team. The greatest challenge is in my opinion to get people involved, to get other researchers involved so that the new concept of research data management is really spread across the community.

If I were a catalysis chemist, what do you recommend I do, how should I contact you?

Sara Espinoza: There are numerous ways for people to get involved. For example, each task area within NFDI4Cat has meetings, and people can participate and make their opinions heard. As just mentioned, we are looking for use cases, so people can contact us and just give us use cases to help us develop new ontologies. We have or are trying to establish the Research Data Management School of Catalysis to train scientists, for example, in basic programming and how to work with GitLab. GitLab is a web-based platform that provides version control, project management, and collaboration tools for software development teams. NFDI4Cat has an open repository for software development in GitLab.

We have a form on our website for those who would like to get in contact.

How did you get involved with NFDI? What interested you most about it?

Sara Espinoza: I gave a TED talk during my Ph.D. research called “How UV Radiation and Nanotechnology Make Cancer Treatment Less Harmful” and there I got to know David Middelbeck, who thinks the fundamentals of learning need to adapt to the digital age. He co-founded an organization working to teach people technical skills. That’s how I got into data science. With a little programming skills and readily available, high-quality research data, you can automate everything, and you can use your time for valuable stuff—with programming everything is simpler.

When I started looking for a job, I found my current position as Project Coordinator of NFDI4Cat and found the idea behind it really interesting because I do think that everybody needs to learn these technical skills. It is also critical to make the most of all of the work that has been done and all of the money that has been invested in research and making it accessible for everyone is essential.

Andreas Förster: This is Sara´s personal view, but it can be generalised because our community has to adopt these new technologies, tools, and ways of thinking. As Executive Director, my ultimate aim is to engage DECHEMA as a promoter and driver of these advancements within the community. This is why I am personally engaged in this project. I think it is highly relevant in addition to all scientific topics like hydrogen and the circular economy, it is a new way of thinking, a new technology that will change the future of research and catalysis.

… and maybe it also helps us to understand catalysis better?

Andreas Förster: Yes, indeed. If we have this data available and know about the metadata, then we will have a better understanding of some processes.

Thank you very much for the interview, I appreciate the opportunity to get insights into these changes happening in chemistry.

Reference

[1] Abel Salazar, Bianca Wentzel, Sonja Schimmler, Roger Gläser, Schirin Hanf, Stephan A. Schunk, How Research Data Management Plans Can Help in Harmonizing Open Science and Approaches in the Digital Economy, Chemistry – A European Journal 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.202202720

Andreas Förster, born in 1966, studied chemistry at the University of Würzburg, Germany, and obtained his Ph.D. in physical chemistry from the same university in 1997. In the same year, he became a part of DECHEMA, where he has held various positions, with his most recent role being Executive Director.

Furthermore, he holds the position of Coordinator for the National Technology Platform SusChem Germany and is Spokesperson and Coordinator of NFDI4Cat.

Sara Espinoza earned her Bachelor’s degree in Biotechnology and Process Engineering at Flensburg University of Applied Sciences and her Master’s degree in Biomedical Engineering at Münster University of Applied Sciences. In 2019, she obtained her Ph.D. from the University of Osnabrück, Germany, graduating with magna cum laude honors. Since 2021, she holds the position of European and National Project Coordinator at DECHEMA.

Selected Links

- NFDI4Cat website

- NFDI4Cat – Digital Chemist Award

Also of Interest

- Christoph Wulf, Matthias Beller, Thomas Boenisch, Olaf Deutschmann, Schirin Hanf, Norbert Kockmann, Ralph Kraehnert, Mehtap Oezaslan, Stefan Palkovits, Sonja Schimmler, Stephan A. Schunk, Kurt Wagemann, David Linke, A Unified Research Data Infrastructure for Catalysis Research – Challenges and Concepts, ChemCatChem 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/cctc.202001974

- Vera Koester, Alexei Lapkin, Interview: The Future of Making Molecules, ChemistryViews 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/chemv.202300003

Alexei Lapkin, University of Cambridge, UK, on the state of the art and challenges of transforming chemistry into the digital realm