The 13th Helsinki Chemicals Forum (HCF) was held as a hybrid event for the first time this year. Most of the over 200 international participants attended the physical event on June 8–9, 2022, at the Helsinki Expo and Convention Center, Finland, to share and discuss relevant aspects of chemicals safety and regulations. Also, for the first time this year, the conference was held in conjunction with the ChemBio Finland and PulPaper trade shows. Participants were able to visit both fairs and take part in their conference programs.

ChemBio Finland is the event for chemistry and biotechnology professionals from the Nordic countries and the Baltic region, where more than 90 companies presented their products. It had a conference program with eight parallel tracks and was organized in cooperation with the Finnish Chemical Society, FIB Finnish Bioindustries, and the Chemical Industry Federation. PulPaper is the leading event for the global forest industry to discuss the latest technologies, where about 250 exhibitors presented their companies. It was organized in cooperation with the Finnish Forest Products Association. In total, more than 6,000 people visited the events.

For me, it was the first international meeting after the coronavirus pandemic, and I incredibly enjoyed meeting many friends and acquaintances again as well as making new contacts. As much as I appreciate online meetings, I once again became very aware of what I have been missing over the past few years and how much easier physical meetings make it to collaborate and share ideas, and all that while following the presentations, exploring the exhibition booths, enjoying the Finnish cuisine, and experiencing that the sun barely sets in Helsinki at this time of year.

Online meetings also have their advantages. Since the HCF 2022 was held as a hybrid event, over the next three months you can re-listen to presentations and discussions that you found particularly interesting or that you missed. You can also still register online if you did not attend the conference.

To truly connect the three events—HCF, ChemBio Finland and PulPaper—all three started with a joint session, the Green Economic Business Summit. Here, company leaders discussed how to ensure adequate economic well-being while reducing environmental impact—a major topic of each event as well. The company leaders gave examples on how the chemical industry commits itself to strict targets in terms of climate neutrality and sustainability.

1 The EU’s Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability (CSS)

The European Union (EU) is considered a leader in protecting human health and the environment. REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorization, and Restriction of Chemicals), the cornerstone of the EU’s chemical legislation, was enacted in 2007 to better protect people and the environment from harmful chemicals. It remains the most comprehensive regulatory framework for chemicals in the world and serves as a model for many other countries [1].

As part of the EU’s Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability (CSS), a key element of the European Green Deal (the EU’s new strategy toward a toxic-free environment), the REACH Regulation will be amended and strengthened. This will have major implications for the EU chemicals industry, downstream users of chemicals, producers of articles, and end-users in various sectors. How this revision can be efficiently managed is a subject of discussion.

Chemicals are an integral part of our daily lives, and their importance continues to grow. They are the building blocks for the goods we use as well as for high-tech materials needed for, e.g., a circular and climate-neutral economy. Europe (EU27) is the second-largest chemical producer in the world (14.4 %) after China (44.6 %). It is important that the chemical industry in Europe—as an important factor for prosperity in Europe—maintains its competitiveness and remains a world leader and a highly innovative sector [2].

This must not be jeopardized by additional regulations to protect the environment and human health. Instead, regulations must be such that they lead to more innovation. At least this is the plan of the European Commission. Europe is considered a pioneer with its REACH regulation. Many participants I spoke to said that what is happening in Europe is happening a little later elsewhere. The USA is far behind, but China is catching up very quickly. For example, in May 2022, the General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China officially released the approved Action Plan for New Pollutants Treatment [3,4]. Among other things, the government plans to gradually introduce and improve laws, regulations, and management systems on chemical-related environmental issues.

The idea is for the EU to take the lead in creating attractive framework conditions and thus strengthen the global position of the European chemical industry. One issue of great importance in this context is the circular economy. Factors such as immigration, digitalization, populism, increasing competition from other regions, comparatively high energy prices, innovation lag, high labor costs, regulatory and tax burdens, and research and development (R&D) intensity will strongly influence the development of the chemical industry in the coming years.

We can be really proud of what we have achieved with our chemical legislation, both in terms of protecting our citizens and the environment, and as an inspiration to the rest of the world, Kristin Schreiber, Director at the European Commission, emphasized in her talk. However, there are areas where we need to do more, and to do that, our processes need to become faster and more efficient. That is why REACH and CLP (classification, labeling, and packaging) are being revised. The primary aim is to accelerate action in three areas: those for which we have taken too long, those where there are legislative gaps, and those where the procedures turned out to be far too complex.

The European Commission’s strategy includes the following action plan:

- Banning the most harmful chemicals in consumer products; allowing these chemicals only where their use is essential.

- Considering the “cocktail effect” of chemicals when assessing chemical risks.

- Gradually banning per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in the EU unless their use is essential.

- Promoting investment and innovation capacity for the production and use of chemicals that are designed to be safe and sustainable throughout their life cycle.

- Promoting the EU’s supply of critical chemicals and their sustainability.

- Establishing a simpler process for assessing the risks and hazards of chemicals based on the principle of “one substance, one assessment”.

- Advocating for and promoting high safety standards for chemicals worldwide and no export of chemicals banned in the EU.

According to Kristin Schreiber (right), Director at the European Commission, the EU’s competitive advantage will not be affected by the CSS if it is implemented properly.

Kristin Schreiber thinks that the successful implementation of the chemicals strategy is a prerequisite for the European chemical industry to remain competitive in the long and medium-term. Europe has a very innovative, modern, and advanced chemical industry because new solutions have been found continuously. If implemented correctly, the CSS will create a major innovation and competitive advantage for the European industry. We can set the scene and set the standards and markets that the others have to adapt to. But “we need to make sure that we get it right”. She asserts that the European Commission is, of course, aware that the chemical industry currently faces many challenges, and whatever is done in terms of regulatory transition and change has to take the chemical industry with it, and that there has to be planning certainty.

A regulation is only as good as it is applied. The very constructive and sometimes, of course, critical feedback is very important and welcome, she concludes.

The chemical industry expects the CSS regulatory changes to affect about 28 % of its portfolio. Presumably, one-third of this can be substituted and/or reformulated. In addition to the question of whether this is technically and economically feasible, the question for the industry is how its customers will react to the substitutes and/or reformulated products. A reduction in product portfolio and business volume (in terms of sales) of about 12 % or EUR 70 billion of the 2019 market is expected, according to the European Chemical Industry Council (Cefic) [5].

Commitment to Safe and Sustainable Chemical MixturesAt the event, the Downstream Users of Chemicals Coordination Group (DUCC) celebrated twenty years of active engagement for a successful chemicals policy in Europe. DUCC is a platform of eleven European associations representing industry sectors that formulate mixtures (for consumers and professional or industrial users) ranging from cosmetics and detergents to aerosols, paints, inks, toners, printing chemicals, adhesives and sealants, construction chemicals, fragrances, disinfectants, lubricants, and the chemical distribution industry. Membership includes more than 9,000 companies [6].

DUCC was founded in 2001 following the publication of the European Commission’s White Paper “Strategy for a Future Chemicals Policy” which eventually led to the launch of REACH in 2007. Since then, DUCC has focused on the needs, rights, duties, and specifications of downstream users under REACH and CLP and is in regular discussion with the European Commission (EC) and the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) to ensure that downstream users’ concerns are appropriately addressed. DUCC is, for example, a founding member of two important ECHA initiatives on supply chain communication: the Exchange Network of Exposure Scenarios (ENES) and the Chemical Safety Reporting/Exposure Scenarios Roadmap (CSR/ES Roadmap). DUCC also sees itself as an important discussion partner as it has the expertise to help define concepts and find appropriate solutions to effectively implement REACH and CLP regulations to improve the workability of the system. It sees itself, therefore, in a key role in implementing the new Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability. DUCC calls for the use of science- and risk-based approaches at the core of any legislative decision, the ability to enable innovation and competitiveness, alignment with global standards such as the United Nations (UN) Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS), and the need to ensure a smart transition to the digitization of information. |

2 Experts on Challenges and Questions Related to the CSS

As usual, the HCF consisted of keynote presentations and panel discussions on current topics, this year mainly on the EU chemicals strategy. The discussions included short presentations and were moderated by representatives of the European Chemical Industry Council (CEFIC), the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), the European Commission (EC), the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

Dinner hosted by the City of Helsinki at the Empire Room (Old Court House). Welcome by Esa Nikunen (left), Director-General of the Environment Centre of Helsinki City, and Geert Dancet (right), Secretary-General of Helsinki Chemicals Forum.

With REACH, Europe has a sophisticated, worldwide unique system—even if we initially thought it would not work—which is a solid foundation [7]. Never before has so much data been collected on chemicals. They are freely available. But with micromanagement, ECHA spends a lot of time reviewing the same substances and groups instead of focusing more energy on harmful substances.

What is needed is a change in thinking. Chemicals need to be safe in the first place, and we need criteria to develop such chemicals in the best way. In Europe, we have very good conditions for this in terms of knowledge and financing. ECHA can help with its expertise.

2.1 Accelerating the Regulation of Chemicals

A panel discussion addressed how to accelerate regulatory decisions and actions for the most harmful chemicals, how the EU will ensure that faster regulatory actions are efficient and targeted while promoting green innovation, and what scientific principles should apply.

The production capacity of the global chemical industry nearly doubled between 2000 and 2017, and it is expected to double again by 2030 [8]. Approaches to promote sound chemicals management—including those to identify hazards and assess exposure—are often complex and slow which means that humans and the environment are unnecessarily exposed to harmful chemicals. Authorities worldwide are, therefore, under pressure to ensure adequate regulatory tools and measures to effectively control them.

The EU is revising parts of its chemical legislation, including REACH and CLP, to expand the categories of the most harmful substances and to be able to apply a faster hazard-based approach to such substances. Tools to do this include the grouping of substances (relevant information from analogous, or “source”, substances is used to predict the properties of “target” substances), a generic approach to risk management (automatic trigger of pre-determined risk management measures—e.g., packaging requirements, restrictions, bans—based on the hazardous properties of the chemical and general exposure considerations), and the concept of essential use (evaluates if substances of concern are essential for a particular use to provide a holistic approach). Currently, chemicals management mostly follows a risk-based approach, where the chemicals of highest concern are evaluated individually. Given the large number of chemicals, this approach is very time- and resource-consuming.

The EU is also working to streamline and simplify the regulatory framework, including accelerating risk assessment and management procedures. A first example of this is the proposed restriction of the large group of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs). Under the proposal, only essential uses of these chemicals will be allowed.

Tatiana Santos, Policy Manager for Chemicals and Nanotechnology at the European Environmental Bureau (EEB), Brussels, Belgium, believes we need full speed ahead now to accelerate regulatory action. We need to do better because regulators currently allow chemicals with unknown safety risks onto the market and then take years to understand and restrict the many potentially harmful substances. Industry refuses to provide adequate and reliable hazard information as required by law, delaying the process. Cheap and dangerous chemicals are still being used, even though safer alternatives are available. This results in more years of unhealthy exposure for people and nature, she continues.

During a discussion: Bisphenol A is an example of ECHA’s lengthy and complex process for issuing scientific opinions, followed by a long period of time for the European Commission to translate them into regulatory action, according to Tatiana Santos (second from left), Policy Manager on Chemicals and Nanotechnology at the European Environmental Bureau (EEB), Europe’s largest network of environmental citizens’ organizations.

The EEB thinks that European laws to control the use of hazardous chemicals have enormous potential, but it calls for setting binding and strict targets for the generic risk approach (GRA), writing strict deadlines into the law, applying the principle of “no data, no market” and showing zero tolerance for non-compliance, putting health before profit by applying the precautionary principle, identifying, assessing and regulating groups of chemicals, and simplifying the system by banning non-essential uses of Substances of Concern (SoC).

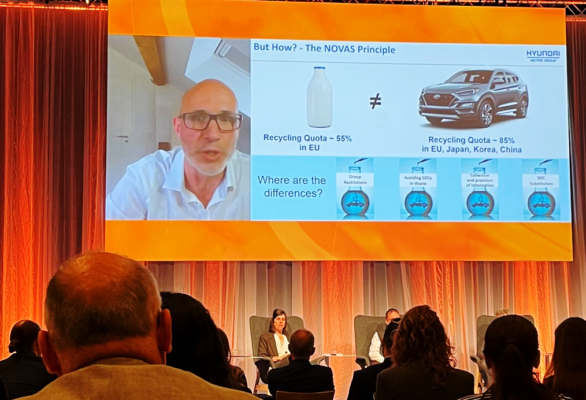

Timo Unger, European Research and Development Center, Hyundai & Kia Motor Company, Frankfurt, Germany, sees clustering as an alternative and smarter approach instead of grouping for the circular economy.

2.2 Safe and Sustainable by Design (SSbD)

A panel discussed how best to define and stimulate safe and sustainable by design substances that can replace substances of concern. To achieve the vision of a toxic-free environment while increasing the competitiveness of the European industry, the CSS announces the development of safe and sustainable by design (SSbD) criteria as well as a network to promote cooperation and information sharing across sectors and value chains and to provide technical expertise.

Christopher Blum, Sustainable Chemistry Scientific Officer, UBA (German Federal Environment Agency), Dessau, believes that SSbD should not only translate into improving the safety and sustainability of substances or materials but also into reducing the demand for materials and products.

Joel Tickner, Professor and Executive Director, Lowell University & Green Chemistry & Commerce Council, MA, USA, reminded the audience that most chemicals on the market were not designed to be safe but to be functional. However, economic research shows that people are willing to pay more for sustainable products and that these products are growing much faster in the marketplace. Nevertheless, he believes it is essential to keep asking the question: Do we actually need this chemical to perform a certain function? Do we even need this functionality?

Chemistry is not always the answer: A chemical can also be replaced by a modified process or service, such as instead of replacing bisphenol A in cash registers with another chemical, electronic receipts are used. You might call this functional substitution.

It will be necessary to educate current professionals and the next generation of leaders to integrate this thinking about safety and sustainability into the design phase.

2.3 Risk Management for Chemicals, Circular Economy, and Climate Policy (3Cs)

REACH focuses on risk management of hazardous substances and substitution of the most hazardous substances to reduce the exposure of workers, citizens, and ecosystems as much as possible. According to the CSS, a hazard-based approach would become the rule for managing chemicals of concern. Risk-based management, which has been used by REACH to date, is to remain the main principle for regulating other hazardous chemicals. Two other policy goals that also underlie the Green Deal are climate neutrality by 2050 and circular economy. These three goals are often referred to as the “3Cs”, representing chemical safety, circular economy, and climate.

|

Chemical substances can be regulated hazard-based or risk-based. In a hazard-based approach, substances are regulated based on their intrinsic properties, without considering exposure to the substance. In a risk-based approach, exposure is taken into account. The European Commission gives the following example on its website: A lion is intrinsically a hazard. Safely caged in a zoo, it poses no risk because there is no “exposure.” “Hazard-based” and “risk-based” decision making on chemicals: what is the regulatory context?, European Commission (accessed June 14, 2022) |

When assessing a chemical risk, it is important to also assess the impact on climate and the goals of circularity. A panel discussed whether and how chemical risk management can be aligned with circularity and climate policy objectives. And what this means for the review of REACH and CLP.

We need to keep several important elements together, some of which are conflicting, so it will not always be a win-win situation. We wash our clothes or laundry only at 30 °C and are happy to save energy. But along the way, we are shifting the problem to the substances like biocides in washing detergents that are entering the environment. We need to stop this, and instead need a holistic approach.

Lively discussions and enthusiastic speakers.

The panelists agreed that a clear prerequisite for success is better information sharing. There is a study underway that calls for environmental footprint data to be submitted at registration. This will not happen tomorrow, but it is certainly an idea that would allow the 3Cs to be better integrated and taken into account.

When you think about the circular economyin a more holistic way, it is not just about putting a chemical or material into circulation now and making that safe from a chemical point of view and for the climate. The panelist gave the following exampe: Right now, hopefully, all cars have catalytic converters to prevent air pollution. These are full of precious metals. Now if we switch to electric vehicles, they will not be needed anymore. The material will hopefully be recycled.

Circularity should also work when we do not need the recycled materials for the next two decades. Who is going to store them, what is going to happen to them? So it is not just about looking at the circular economy with the three Cs as a photo (now), but also as a film (span of time) to make sure that we can fight climate change in a circular economy without harming human and the environment. That requires a new way of thinking and dealing with material flows.

Creating a circular society is not just about economics. It is not just about collecting these materials and someone miraculously turning them into a new product. That is why it is important that in the future we put recycling in its proper, limited role, not at the center of a circular economy, but actually thinking about how we design problems so that we avoid the impacts in the first place.

A panelist said their salary does not usually allow them to afford something like a fair phone, but they decided to buy a fair phone to show that this kind of product is needed in the market. It can be upgraded, its lifetime can be extended, and the company cares about where some of its very important raw materials come from.

And social responsibility starts earlier: Consumers need to bring back things like an unused phone so it can be recycled instead of hoarding old items. People should remember they are part of the recycling process, and the recycling is not only efficient recycling and bending but also bringing things back on time.

Coming back to conflicting elements: If we want to combat climate change through renewable energy, then the next few years, the next decades are crucial to implementing various transformations. We will need an enormous amount of new materials for this, e.g., renewable energy devices. In the long term, of course, we need to design these so that they can be recycled afterward, but that is something that unfortunately we cannot realize in the short term.

2.4 Replacement of Animal Toxicity Testing

A panel discussed how to ensure that alternative testing methods are as protective of human health as the animal models they replace, and what global harmonization might look like.

Global regulations increasingly aim to limit or eliminate the use of animal testing in evaluating the safety of chemicals. In addition to the interest in eliminating animal testing for humane reasons, animal testing is time-consuming, costly, and may not accurately predict the effects of chemicals on humans. Biotechnology has produced a variety of non-animal test protocols. However, the application of these methods to regulatory decision-making remains relatively slow.

The science is evolving, and the panelists feel that now is the time to make the transition. There are some real challenges, especially with things like systemic and complex endpoints. The new approaches are not more uncertain; they bring an unfamiliar uncertainty that we need to get comfortable with. Once new methods and interpretive approaches are established, there are a large number of chemicals for which there are no data. For these reasons, increased collaboration between regulators, researchers, and industry is needed to develop short- and long-term goals for replacing animal testing.

3 The Cost of Inaction

We know that we cannot continue as we are. We need new ways of thinking, new solutions, and we are running out of time. David Azoulay, Managing Attorney in Geneva, Director of the Environmental Health Program, CIEL, Switzerland, calls the cost of inaction one of the biggest challenges. “We keep focusing on what it would cost to do something, and we tend to assume that doing nothing costs nothing. It doesn’t cost the same people, but the cost is actually huge. An important step in solving this problem would be to find a way to internalize the costs of externalities.”

Costs and benefits can be very different in different parts of the world. Clearly, the big picture is needed for proper decisions. But we seem to like to retreat behind too few facts or too complicated contexts.

There must be a social agreement on what we want to achieve. This must be clear before data is collected because otherwise, we end up with the same discussion over and over again about more information on this or that aspect being necessary.

And we need to communicate better. Sir Robert Tony Watson, who, among other things, chaired the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) from 1997 to 2002, suggested if-then approaches. If you want to achieve the following, these are the options for achieving it. If you want to avoid the following, here’s what you can do.

Problem solvers are farmers, forest owners, the chemical industry, the bio-industry, … probably/hopefully all of us.

The next HCF will take place in April 2024 together with the exhibitions ChemBio Finland and PulPaper.

References

[1] REACH – An Overview, ChemistryViews 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/chemv.201200029

[2] Facts and Figures of the European Chemical Industry, Cefic (accessed June 14, 2022)

[3] China Releases Action Plan for New Pollutants Treatment, REACH24H May 26, 2022. (accessed June 14, 2022)

[4] 国务院办公厅关于印发 新污染物治理行动方案的通知 国办发 (General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China officially released the approved Action Plan for New Pollutants Treatment), May 2022.

[5] Economic Analysis of the Impacts of the Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability Phase I report commissioned, European Chemical Industry Council (Cefic) December 2, 2021.

[6] Downstream Users of Chemicals Coordination Group (DUCC) (accessed June 14, 2022)

[7] Vera Koester, 10 Years of Making Chemicals Safer, ChemistryViews 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/chemv.201700041

[8] UN Global Chemicals Outlook, 2nd edition, UNEP, April 29, 2019. ISBN: 978-92-807-3745-5

- Helsinki Chemicals Forum

- PulPaper

- ChemBio Finland

- The New EU Chemicals Strategy,

Vera Koester

ChemistryViews 2021.

https://doi.org/10.1002/chemv.202100040

Expert discussions at the Helsinki Chemicals Forum included the Green Deal and the EU Chemicals Strategy - Identifying the Best Options for Chemicals Regulations,

Vera Koester,

ChemistryViews 2019.

https://doi.org/10.1002/chemv.201900054

Circular economy, plastic pollution, chemical data access are among the topics discussed at Helsinki Chemicals Forum (HCF2019) - More on Chemicals Legislation