Plants have been used to color creative works for centuries. One such plant, Chrozophora tinctoria, is known as dyer’s croton, dyer’s litmus, or turnsole. It has been used to make a blue-purple pigment, also called turnsole, for the best part of a thousand years—from the medieval period well into the 19th century, and perhaps even to this day in some niche artisanal crafts. Turnsole is an archaic name for both the plant, a member of the spurge family, and for the pigment, which also goes by the names katasol and folium.

Turnsole was originally spelled tornasol, meaning “turn to the sun” and alluding to the habit of the plant’s flowers to track the sun across the sky over the course of the day. It became a mainstay of medieval manuscript illuminators. As such, there was a rich literature on finding the plant, storing its fruit, and processing it into the dyestuff which was made into a watercolor and then painted onto cloth for later extraction and use in the actual artworks and manuscripts.

Interdisciplinary Work on a Medieval Blue

As with all pigments, chemists are keen to know the chemistry of such vivid chromophores that were used in major works of art, illuminated manuscripts, and even to dye the wheels in Dutch cheese making. Joana Oliveira, Victor Freitas, University of Porto, Portugal, Maria João Melo, NOVA University of Lisbon, Monte de Caparica, Portugal, and colleagues have performed an analytical and computational study to find the chemical structure of this medieval blue.

The team used a recipe from the middle ages to produce turnsole from the shells of the fruit of Chrozophora tinctoria. They brought together a large team of chemists with expertise in natural products identification, conservation scientists working in the reproduction of medieval colors; and a biologist with a great deal of botanical and field knowledge of the Portuguese flora. “This interdisciplinary approach proved essential to solving the complex structure of the blue dye,” the team writes. Moreover, by following the medieval recipe they could be sure that they were producing the exact same dye that had been used on those illuminated manuscripts and had perplexed chemists through the latter part of the 20th century and well into this one.

The team used a wide variety of analytical methods to find the structure of the dye, including high-performance liquid chromatography diode array detector mass spectrometry (HPLC-DAD-MS), gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS), several nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopic techniques (1H NMR, 13C NMR, correlation spectroscopy (COSY), heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC), heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC), and insensitive natural abundance double quantum transfer experiment or INADEQUATE), as well as electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) and UV-Vis spectroscopy.

An Old and Yet also New Type of Pigment

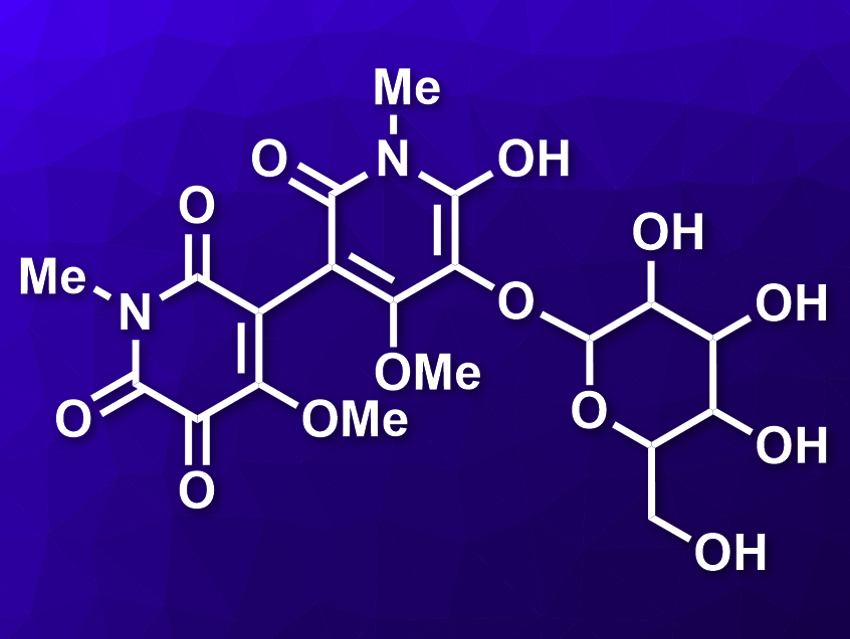

The bottom line: the researchers found that the molecular structure of the dye’s main chromophore is 6′-hydroxy-4,4′-dimethoxy-1,1′-dimethyl-5′-{[3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl]oxy}-[3,3′-bipyridine]-2,2′,5,6(1H,1′H)-tetraone (pictured). The team has named this hermidin derivative “chrozophoridin”. They emphasize the novelty of this newly revealed blue pigment: it is not indigo, obviously, nor is it an anthocyanin of the kind found in the blue-hued petals of various other species of plant. They also revealed the presence of numerous other chromophores of different classes present in the extract from turnsole in minor quantities.

As with many plant extracts, there is not only a colorful and rich artistic history, but a medicinal history too. The ancient Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist Pedanius Dioscorides first described the medicinal properties of this plant in his De Materia Medica in the first century. It is also mentioned in various medieval pharmacopoeia. Studies that focus on extracts with putative antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, possible anticancer activity, and promotion of wound healing have been published in the last few years.

Chrozophoridin is in “a class of its own”, aesthetically and chemically. “We believe that this will be not our final word on this amazing plant and its story and that further discoveries will follow soon,” the team concludes.

- A 1000-year-old mystery solved: Unlocking the molecular structure for the medieval blue from Chrozophora tinctoria, also known as folium,

P. Nabais, J. Oliveira, F. Pina, N. Teixeira, V. de Freitas, N. F. Brás, A. Clemente, M. Rangel, A. M. S. Silva, M. J. Melo,

Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz7772.

https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz7772