Englishman Henry Bessemer (1813–1898) was a resourceful tinkerer and inventor, best known for a process for the production of steel. His 1855 patent “Regarding the Production of Malleable Iron by Blowing Air into a Pool of Molten Iron” eventually brought him lasting fame and immense wealth. Along the way, he made many other discoveries.

In the previous part we looked at Bessemer’s mechanical methode to make gold bronze. In this part, we will take a look at how he smartly outwitted his competitors and what entrepreneurs can learn from him.

5. Competition in Fürth and Nuremberg

Let us take a look at the production of bronze powder from the point of view of Bessemer’s Franconian competition. In the early 19th century, Fürth and Nuremberg were the global market leaders in the production of metal leaf and bronze powder. However, the two cities differed in their fundamental business climate.

In Nuremberg, the manual laborers lived under medieval guild laws, which precisely proscribed who could produce what and in what quantity, and what conduct was acceptable. In Fürth, on the other hand, the first, significantly more liberal manual craft laws were passed at the end of the 18th century. The city used this to take in journeymen and masters who had been banned from working in Nuremberg due to infringements against the guild rules.

The guild rules in Nuremberg only allowed their gold beaters to work with gold and silver, while the Fürth craft laws for gold, silver and metal beaters expressly allowed them to also work with non-precious metals such as brass.

5.1 True Gold Leaf

Real gold leaf was produced in Franconia as early as the middle ages. Pieces produced during cutting and unusable gold leaf (known as schabin) were collected and processed into “ground gold”. This was carried out in mortars with a grinding fluid consisting of gum arabicum, water, and salt, allowing the gold foil to be torn into small pieces by rubbing. After grinding, the metal powder was washed out and dried. This formed the true gilt that was stirred into a binding agent and used for such things as book illuminations and for gilding works of art.

5.2 Bronze Powder Made of Brass

From about 1830 on, the inexpensive bronze powders made from brass were so popular that they were produced in large quantities. In many companies the production of metal leaf and metallic powders were carried out in parallel. Manual production of the metal leaf used as starting materials for making metallic powders was the same for all metals. In a day’s work, a metal beater wielded a 3 to 12 kg hammer over 50,000 times . After several steps, 0.0001 mm thick leaf made of gold or other metals was produced. This leaf, together with waste material from cutting, was then ground down to make metallic powders.

The manual labor of the metal beaters took a great deal of time, justifying the high price demanded for bronze powder made from brass. This manual production method could not compete with Bessemer’s mechanical process in the long term. Mechanical hammers did make the work easier, but the large demand for fashionable bronze powders could not be met. All of this led to the fall of bronze fabrication in Franconia

5.3 Spies at Baxter House

This situation threatened the existence of the Franconian metal hammer works. It was thus understandable that they tried to track down Bessemer’s secret production method. His excessive secrecy and extreme caution now paid off, because one day something unusual happened near Baxter House:

“Our local policeman told me that the house had been watched from morning until late at night by a person stationed at one of the windows of a public house across the street. I asked, ‘Is he a German?’ He answered, ‘Probably so. At any rate he is a foreigner.’ I commended him for his vigilance and gave him a small gratuity.

At this time, only my three relatives and I worked in the factory. We never left the office at the same time, and when we did leave, we might well have been taken for office clerks, who would know nothing of the manufacture. The foreigner watched for an opportunity to bribe one of my workmen.

And he would have it! After giving him proper instructions, I send our Scottish machinist out through the front door. With his shirt sleeves tucked up, he was the very beau-ideal of a British workman. He was to enter the pub and order something to drink. No sooner had he done so than the stranger came down and asked him:

’Do you work at the bronze-powder factory opposite?’

‘Yes.’

‘Why I ask you is this: I have invented a machine for making hooks and eyes. I need a clever engineering firm to make me these machines. I have been told that you have beautiful machinery over the way, and I should like to give an order for my machine to so eminent an engineer. Do you know who made all the machinery at your works?’

‘I don’t know, but I can enquire.’

‘Meet me here when you leave work tonight, and if you can let me know who made your machinery, I shall reward you handsomely.’”

The loyal machinist informed Bessemer about the conversation. When they met again in the evening, the machinist informed the stranger that all of the machines had been planned by a Mr. Henry, and that he would be expected the next day at 11:00 at No. 4 North Street. This was the address of Mr. Bessemer’s brother. Punctually at 11:00, the stranger came and rang the bell. He was directed into the dining room, where Henry Bessemer awaited him:

“’Have I the pleasure of seeing Mr. Henry, the engineer who designed all the machinery at the bronze-powder factory at St. Pancras?’

‘Yes, I designed the whole of it.’

‘Ah, I am so glad thus to make your acquaintance; for this purpose, I have come over from Bavaria, and wish you to construct a duplicate of it for me.’

‘Well, this is not possible, for I am so deeply engaged with new inventions that I could not undertake to furnish you with plans or drawings.’

‘But I shall pay you anything you demand in reason, so it may answer your purpose to lay aside other things for a time.’

‘I cannot give you the plans I have developed for another manufacturer, but as you have come such a long distance, I can at least give you an overview of how to inexpensively produce bronze powder.’’

Bessemer then outlined for him his first process, which had been such a dismal failure (see Part 2, chapter 3). The unknown German was delighted and profusely thanked Mr. Henry.

“I have often wondered whether, on his return to Bavaria, he tried to put in practice this impossible mode of making bronze powder. If he did, the disappointment he would experience would be only fitting punishment for his meanness in trying to bribe those who were in possession of my secret.”

5.4 Bessemer Prevented Industrial Espionage

It is hard to believe today, but Bessemer accomplished the impossible: He and his trusted coworkers kept his production process secret for over 35 years, which provided longer protection than any patent. It is hard to imagine how Bessemer managed, in his everyday life, even as a host, to deflect any requests from curious acquaintances, distant relations, or good friends to have just one short glimpse into his factory. He remained consistent.

Only five people ever entered the factory. Curious visitors were told: “No, you will find much greater amusement at the theatre, and tonight you might prefer to go there.”

6. Fürth Strikes Back

Years later, Bessemer traveled to Germany with a German friend, who had imported bronze from Fürth to England. The trip included a visit to Nuremberg.

“After a few days in Nuremberg, we visited the little nearby town of Fürth, the principal seat of German bronze manufacture. We visited a former business associate of my friend and spent a very pleasant day with this gentleman’s family; the weather was delightful, and we were able to sit under the trees in the open square, enjoying light beer and returning at night to Nuremberg.

On the second day after our visit to Fürth, our landlord told us that two police officers were awaiting our return, and had papers for our arrest. We were greatly astonished, but had no doubt this was some huge mistake; however, it was not so, and we found that the order was to arrest an Englishman of the name of Bessemer. Our landlord wanted to help, and suggested that we should remain in charge of one of the officers at the hotel, while he and the others went to the police office to clear up the mistake.

After a while, the landlord returned with an official summons to appear before the magistrate at eleven on the following morning. There I was told that I was charged with a very grave offense in Bavaria: Attempting by bribery to induce a workman in the employment of a bronze manufacturer at Fürth to go over to England and assist in opening a factory on the model of that of his employer. I was accused of offering the man 2,000 thalers. I explained to the magistrate, who spoke excellent English, that for years, I had, with three attendants, been manufacturing daily as much bronze powder as eighty men could produce by the system then in use at Fürth. The idea of wishing to copy this old mode made no sense. I further stated that the charges were ridiculous because I spoke no German. ‘If you, sir,’ I said, ‘will ask my accuser what I offered him and what was said on both sides before finally settling to give him 2,000 thalers for his services, you will readily convince yourself of the absolute falsehood of the charge, which could only have been made in pure spite or envy.’

A long talk in German between the magistrate and my accuser ended in the magistrate saying that I was dismissed and found not guilty of the charge laid against me. He also said I must leave Nuremberg by post wagon that same afternoon. I expressed my astonishment at this treatment, telling him that I wished to stay in Nuremberg for several more days, and I intimated that I should at once ask the protection of our Minister in Munich.

’It is for your own protection that I wish you to go. If you stay here, you will be stoned.’

’Surely, said I, ‘after such an abominable charge has been brought against me, I cannot sheer off in so cowardly a manner, and must look to you for protection during my stay here.’

‘The judge replied, resignedly, ‘Well, if you wish, you can have the protection of two officers wherever you go.’

I thanked him and accepted the escort he had offered. This was rather good fun at first, but it soon began to be very irksome. We were stared at everywhere and had to pay for the admission of these men at all the places of amusement we visited; so we hurried our explorations of the very interesting old town of Nuremberg and commenced our return journey.

I have never found out the facts, but I have always strongly suspected that this charge was got up against me to pay off the little trick on the German spy. However, ‘All’s well that ends well’; and I was glad to return home from a very enjoyable holiday, ready to set to work again on whatever might be set before me.”

7 Closing Remarks

Henry Bessemer did precisely this for the rest of his life. Thanks to the bronze powder, he was able to exercise his inventive genius without financial worry and registered a total of 115 patents.

One would almost get the impression that there is almost nothing that he would not have invented and brought into production. In cases of failure, he was mostly ahead of his time. It was said of Bessemer that he searched out or gave himself obstacles to overcome them and achieve much success.

Henry Bessemer was celebrated and much honored. He was an honorable citizen of Hamburg, Germany, and was knighted by Queen Victoria. He was highly renowned at his death on March 15, 1898, in London.

8 The Bessemer Converter

The Bessemer converter was a milestone for the industrial production of steel. It made steel a high-quality and inexpensive material for industry.

The extraction of iron in a blast furnace is chemically a reduction of oxidic iron ore with carbon (coke). This produces pig iron, an iron alloy containing 4 to 5 % carbon, up to 3 % silicon, 6 % manganese, and trace amounts of phosphorus and sulfur. Pig iron can be combined with scrap and other additives to make cast iron with only 2 to 3 % carbon. Pig and cast iron are brittle and cannot be shaped by forging or milling.

Larger quantities of malleable iron did not become available until the 1784 invention of a new puddling process by Henry Cort. In this process, pig iron was melted in a pan, and several men had to stir the exposed molten metal with long poles for 24 hours, bringing the iron into contact with oxygen and burning off the dissolved carbon. Once the carbon content is below 2 %, the metal is considered to be steel. The puddle process was very labor-intensive, required a lot of time, and could only be carried out on quantities of at most 200 kg.

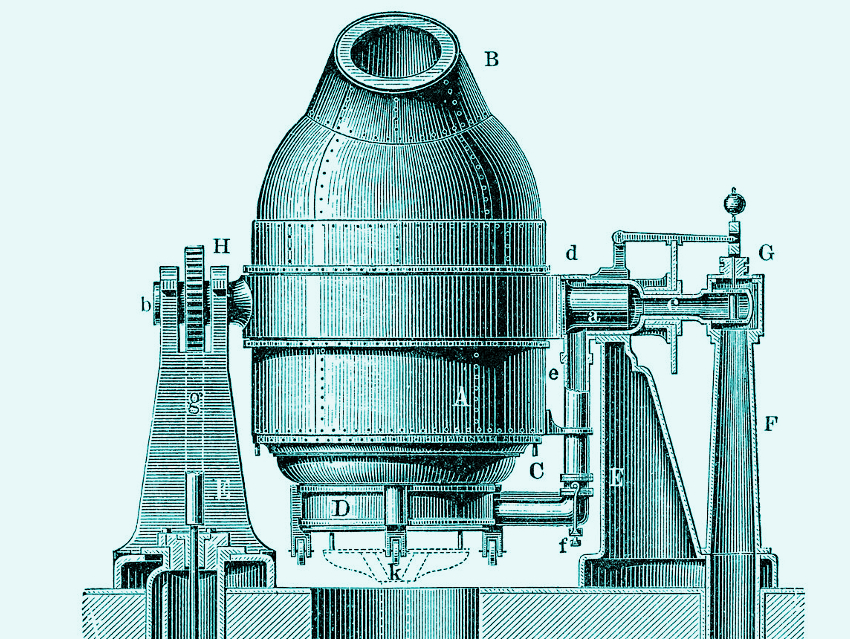

This is where Bessemer got into the game. He experimented with a self-stirring puddling furnace and recognized that the oxidation of the carbon in pig iron by oxygen in the air is the chemical basis of steel formation. Bessemer constructed a tiltable container, called a converter (see Fig. 5), for processing 10 to 30 tons of pig iron. The conversion of pig iron to steel occurs in three steps:

- The converter is tipped horizontally and filled with molten pig iron (B in Fig. 5).

- The converter is then tipped up and pressurized air is pumped in from the bottom through pipes (C).

- After 15 minutes, the airflow is stopped, the converter tipped (D), and the liquid steel poured out (E).

Figure 5. Bessemer converter. Left: Schema of a Bessemer converter. Right: Bessemer converter, outside the entrance of Kelham Island Museum, Sheffield, UK (Chemical Engineer).

As air begins to enter the melt, the strongly exothermic oxidation of the carbon causes a giant roar as an impressive blast of fire exits the converter in what is surely the most spectacular industrial oxidation reaction.

Bessemer’s process marked the beginning of the mass production of steel and was a technological breakthrough whose importance as a driving force for the heavy industrialization in the second half of the 19th century can hardly be overstated. Bessemer’s process was a fizzing source of cash for its inventor: Through licensing, he received 1 pound sterling for every ton of steel produced until the patent ran out in 1869. And steel was produced in huge quantities – about 100,000 tons in 1865 alone.

9. Sir Henry’s (Conjectured) Advice for Entrepreneurs

Henry Bessemer’s work methods and approach at the start of industrialization cannot be applied directly to modern conditions, because investors that rely on the word of the inventor have long since disappeared. However, in a thought experiment, we can ask ourselves what advice Sir Henry Bessemer would give to young entrepreneurs today. Possible the following:

- Think boldly and pursue your ideas.

- Recognize failures early and accept them – they are a part of progress.

- Defeats can move you forward, but only if you stand right back up and apply yourself to new goals.

- Always maintain an observant mind and recognize lucky accidents. You sometimes get a second chance and past failures can become successes.

- If your loved ones ask a favor, fulfill it. This can lead to fortune.

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr. Sabine Streller, FU Berlin, Germany, for her creative support, Dr. Norbert Ott, Berlin, for his critical and constructive manuscript revision, and Ulla Eder for her spontaneous assistance during my visit to the City Museum of Fürth, Germany.

References

[4] Industrial Heritage, Steel Making by Bessemer Convertor at Workington Cumbria, YouTube 2013. Link: www.youtube.com/watch?v=qJ3aTpKMmfQ (accessed November 4, 2019)

Professor Klaus Roth of the Free University of Berlin is a regular contributor to ChemistryViews

The article has been published in German as:

- Sir Henrys geheimer Goldschatz,

Klaus Roth,

Chem. unserer Zeit 2018, 52, 416–425.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ciuz.201800876

and was translated by Caroll Pohl-Ferry.

Sir Henry’s Secret Pot of Gold – Part 1

A true fairy tale for entrepreneurs—with a rocky start

Sir Henry’s Secret Pot of Gold – Part 2

Henry Bessemer’s breakthrough method to make gold bronze

Sir Henry’s Secret Pot of Gold – Part 3

How Henry Bessemer would advise modern entrepreneurs and how he smartly outwitted his competitors

See similar articles by Klaus Roth published in ChemistryViews