“Impact Factors Make our Task More Difficult”

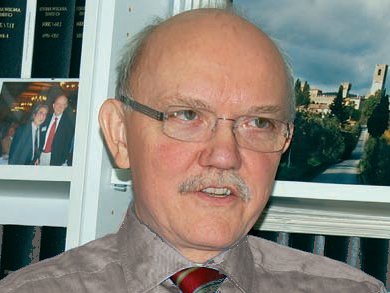

Angewandte Chemie is seen to be the flagship of the GDCh journals. Nachrichten aus der Chemie, the GDCh membership magazine, asked Peter Gölitz, the Editor-in-Chief of Angewandte, why this is.

Dr. Gölitz, as you began, JACS, the Journal of the American Chemical Society, was the leading international chemistry journal, and Angewandte was in contrast an almost purely German publication.

In those days, many, many German authors submitted their best work to JACS. It was clear to me that we had to win top chemists from the USA and attract them to Angewandte. It took a decade until we received significantly more contributions from there. 30 years ago, 10 % of the manuscripts came from overseas and 90 % from Germany — today it is the other way around, and we still receive twice as many manuscripts from Germany.

How did you achieve this?

It was important to approach people personally. I went to all lectures that were nearby to convince American chemists that they should try publishing one of their good contributions in Angewandte.

Many now say that Angewandte has overtaken JACS as the market leader.

JACS was and still is a very good journal. But in the eighties there was one thing that didn’t exist then but dominates nowadays: the impact factor. Practically the only thing that mattered then was having personal contacts, and we had an advantage with a strong in-house editorial team. At the time I began, apart from the editor-in-chief, there were two editors for the German and two for the English version of the journal. Today we have about 20 editors, all with doctorates in chemistry. For journals with professors who do the job in effect as a sideline, approaching authors directly at the scale that is normal for us isn’t possible.

The author–journal relationship is therefore essential?

es, but so are the referee–journal and reader–journal relationships: the readers are also authors and the authors are referees and the referees are readers. Shortly before I began at Angewandte, the editors had begun with the wonderful circular title-page pictures. When a reader came into the library — in the days when a reader had to go to the library to read a journal — he/she was magically drawn to the Angewandte, and so starts the reader–journal relationship.

Does the kudos that Angewandte nowadays enjoys make the task simpler?

No, it is actually more difficult. The editors have to get through at least twice as many manuscripts nowadays as they used to 25 years ago when we received 500 manuscripts per year — now that number is around 7000.

The Burden of the Impact Factor

One reason that authors like to publish in Angewandte is no doubt the impact factor of over ten. Do you believe in impact factors?

I am in no way a fan of impact factors. They have made our life more difficult.

More difficult?

Definitely. More and more authors believe that they have to get their work into a journal with a high impact factor, even though a level lower would be more realistic. At the time I began, we rejected 20 % of the manuscripts, and in 2009 it was 78 %.

Are authors losing their awareness for their target audience?

Worse — there is a loss of realistic self-assessment. And editors that have grown up with this system are also in jeopardy. Let’s not fool ourselves — there are parameters that can be adjusted in order to influence an impact factor. But an editor cannot be drawn by this. If you are producing a journal for a broad audience, like Angewandte Chemie, you also have to publish articles that come from smaller communities, such as inorganic solid-state chemistry, and doing this does not improve your impact factor.

The typical Angewandte readers and authors that drive the impact factor up are, then, synthetic organic chemists?

Not typical, but the most common. The typical reader or author is a chemist that is active in research. Angewandte covers a broader range of topics than it did 20 or 25 years ago.

Really? Older researchers in particular claim that Angewandte has become much more specialized.

No, this is a subjective perception. But no doubt those who are not working in or using organic synthesis could feel like there is too much of it, and in general there is always too much of the stuff one is not interested in.

Do you also identify areas of deficit for which you specifically approach authors?

It is possible that new developments appear that perhaps gain more limelight. Let’s take two buzzwords from organic synthesis: gold catalysis and organocatalysis. It is important to keep an eye on the communities, so as not miss any developments. One must however be careful: every community feels that there is never enough of their field in Angewandte.

Competition

The market for chemistry journals tends to be small. Despite this, new journals keep appearing; is a journal like Nature Chemistry competition for you?

Naturally there is competition among the top journals for the very good contributions. The toughest but nonetheless friendly competition is with JACS. Nature Chemistry publishes less than ten original contributions per issue, and per year this is not even one tenth of what we or JACS publish in Communications alone.

Angewandte is also well-known for its many different types of articles beyond Communications — Highlights, Minireviews, Reviews. How do these contribute to the success?

Significantly — but much less to the high impact factor as many think. Some of these types of articles even have a negative influence, as they are an attractive read but rarely cited. The obituaries that have started appearing in the last two or three years are hardly ever cited, but they have a surprisingly high number of downloads.

Which contributions have the highest?

About 80 % of the top 50 come from the largest homogenous community in chemistry — from those authors who are active in organic synthesis or who use organic synthesis.

How well received are the more personalized forms? Last year for example you started publishing author profiles?

Now authors come to us: “I have just submitted my tenth contribution. What do you need from me for the profile?”

And there hasn’t been any criticism?

There is always some criticism with such things, because some scientists believe that science is something that should only involve itself with facts and interpretations.

Criticism probably always lands directly on your desk. Is Editor-in-Chief of Angewandte a job that makes you liked, disliked, or feared?

Well, criticism doesn’t only land on my desk. Every editor has to be able to take criticism, because compliments don’t come very often. Not that we expect it, but when a rejection comes, or when you have made a mistake, then the criticism is there immediately on your desk. But in the end, I have made many more friends amongst authors, referees, and readers than acrimonious critics.

Are there people who still don’t want to speak to you?

That doesn’t really happen as one of my principles is to approach those from whom I have recently received criticism.

And do they then send their next contribution to Angewandte?

It might take a while — but it is very rare for an author to never come back.

Quality First

Sending a manuscript to Angewandte is only the first step. The big question of course is: what do I have to do so that my manuscript isn’t rejected?

This isn’t a secret. The key is: quality first. The basic requirement is that it is better to invest a quarter of a year or more work in a publication.

How do you keep up this standard of quality?

With our refereeing system. At the time when I started, Angewandte didn’t have any sort of peer-reviewing system. The manuscripts arrived, and you asked someone who you knew for advice — if you wanted any. Many manuscripts were simply accepted or rejected at the discretion of the editor-in-chief. It was obvious to me: if the content or the range of topics wasn’t right, then copy editing alone wasn’t going to lead to a successful future.

Wouldn’t it be an idea to further motivate the referees by publishing their reports, thus showing how they play an important part of the scientific process?

We now have a way of awarding the most productive referees — not with money, but by presenting certificates at the end of the year: “You have produced more than one referee report per month for Angewandte Chemie”. By the way, there are many who produce more than one report per month. And it’s all not about quantity; those referees that we ask most often are those who provide particularly useful comments.

And the idea of making the refereeing process completely open?

That wouldn’t work, because referees occasionally provide extremely critical reports.

Perhaps because they know that they are anonymous?

But there are plenty of manuscripts that have to be heavily criticized! If a paper is weak, and the referee makes this clear, then it hurts — even if the report is not written in a hurtful manner. You can write such criticism in an eloquent and neutral manner, but in the end it is still strong criticism, and these shouldn’t be casually made public. It is an illusion to think that science is a neutral, emotionless affair that is purely based on facts. The ability to take criticism is not pronounced, but nor is the ability to criticize effectively. The point of the criticism is, in itself, hurtful.

Do Famous Names Have it Easier?

Is it easier for famous authors to get published in Angewandte than relatively unknown scientists?

Well, I often hear this allegation. But you can ask well-known authors, and they will confirm it: “Yes, I have also had work rejected by Angewandte.”

But it is apparent that some authors are often to be found in Angewandte.

Let’s take, for example, the author with the most contributions: K. C. Nicolaou has perhaps 20 to 25 postdocs from the best groups in the world in his team. If his group didn’t have such a high output, then something wouldn’t be working right.

A young researcher with two students is happy when they get a couple of good publications in a year …

I am particularly pleased about authors that send their first manuscript to Angewandte. But in borderline cases, you have to ask yourself: Are we really doing them a favor if we accept this work? This phase is in any case very important for the motivation and for their future career, and as editors we are aware of this.

Has the quality of the contributions in the last 30 years increased?

In 1980 there were also many excellent contributions. But the scope of high-quality articles is broader than in those days.

That no doubt applies to the scientific content. But what about the ability to write scientifically?

hemists are trained to become excellent scientists and have a talent for that, but they are not trained to become the best writers and, in most cases, have not the talent for this either. That applied to me as well. But you can learn: I learned how to write letters and to edit.

Can you give science authors one piece of advice to improve the style of their manuscripts: is there a golden rule?

One thought per sentence. It aids comprehension in almost every case when authors don’t try to squash too much into one sentence.

Reading and Browsing.gif)

What do you most like to read when you aren’t reading Angewandte? Sister journals like ChemSusChem don’t count …

Once Angewandte has appeared, I don’t read it any more. But I do read a lot. At breakfast I flick through magazines like Nachrichten, C&E News, Nature, or Science. Otherwise I like to read novels — from Joseph Conrad to Philip Roth, from Vladimir Nabokov to Yasushi Inoue.

Do you read from the computer screen at all?

Neither careful slow reading nor browsing on the computer screen is my thing. Nevertheless it has become clear to me that the printed issues are only a side-product. Our major product has been the online version of Angewandte Chemie for several years now, and every article has to appear in EarlyView first. Everything that isn’t published in EarlyView doesn’t register with many readers. As a consequence, we now publish everything first in EarlyView — including the cover features as “Cover of the Week”.

If this is the case, why don’t you get rid of the print version — after all, print is a cost-intensive operation?

At the moment, a sizable fraction of our revenue still comes from the printed version. And many readers still prefer to browse issues while traveling or in their leisure time. We won’t let this disappear overnight.

That would please many readers. The ACS is taking a different path for some of its journals.

Yes, the ACS prints two pages in one in most of their journals and doesn’t deliver print to personal subscribers anymore.

Perhaps that’s the thought behind it: first make the printed version unattractive, and then it’s easier to finish with it?

I have a different philosophy: either you make the printed product so that it is attractive, or you stop producing it altogether when no-one wants it or it is no longer economical.

Open Access a Way Out?

If we were to look ten years into the future, which publications will still be available in print?

In ten years’ time, Angewandte could still be appearing in print. Many of the specialized journals, and I include EurJIC, EurJOC, and the ChemXChem series, could well be only available online in ten years’ time.

Does the pressure then increase to make everything open access?

Definitely not. It is a myth that open access has anything to do with publishers holding on to the printed form. Publishing companies started placing their journals online a long time ago.

Open access means free access for the reader — is this not an attractive way for publishers to gain the maximum number of readers?

As Editor-in-Chief, nothing would please me more than having as many readers as possible. And you could say that you get the most readers when access is free. But do the readers then really take center stage? With open access, we have to satisfy those who pay for publication — in other words either the authors directly or indirectly via research grant providers and foundations. Do I then have to work on gaining readers and ensuring that the content is understandable, i.e., carefully copy-edited? And how do I decide in the many borderline cases when an acceptance brings cash but a rejection only costs?

Do you then believe that the current system is the better one?

At the moment I see no alternative.

-

Adapted and translated from an article that appeared in the GDCh membership magazine Nachrichten aus der Chemie 58, February 2010, 127–130.